International Financial Reporting Standards

- Details

- Category: Accounting

- Hits: 10,990

A reporting entity (which we will call “entity” from here onwards) is either a company or a group of companies, which are all controlled by the same decision maker, i.e. normally the same board of directors. This occurs when the board of directors of a company controls directly or indirectly a number of other companies, by holding directly or indirectly the absolute or relative majority of the voting rights of other companies.

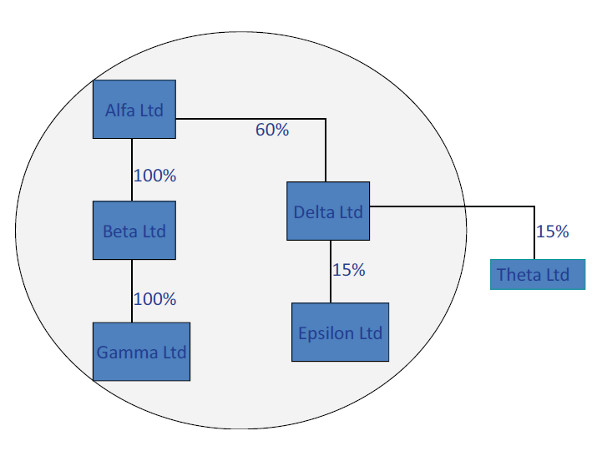

Figure 1 illustrates an example where Alfa Ltd is a company that controls a group of companies made of: Beta Ltd (directly controlled), Gamma Ltd (indirectly controlled), Delta Ltd (directly controlled by absolute majority) and Epsilon Ltd (indirectly controlled by relative majority), whilst Theta Ltd is not part of the group, the Alfa group either exercises significant influence over Theta Ltd or does not, making Theta Ltd respectively either an associate company or simply an investment of the Alfa group.

This simple example is based on the assumptions that the remaining part of the capital1 of Epsilon Ltd is spread among many shareholders, none of which controls more than 15% and that this does not apply to the remaining capital of Theta Ltd. All the companies that are part of the group are subsidiaries of Alfa Ltd.

Figure 1 - Alfa group

The annual report’s contents vary from entity to entity, yet they must include certain compulsory elements, which are required by the legislations of the respective countries where companies are registered and, in case, listed in the stock exchanges; these legal requirements and regulations mostly refer to the provisions of the IFRS - with notable exceptions of countries that have not as yet fully embraced the IFRS.

Several reasons affect the variability of the contents of the annual reports. Firstly, the IFRS allow wide areas of choice for what concerns the formats of the financial statements, implying that the cultural background and past experience of the preparers of the accounts determines what interpretation to adopt, let alone that some provisions’ interpretation are subject of controversy among accountants.

Secondly, the IFRS have been subject to a relatively high-paced development over the last decade or so; normally the changes are phased in, with the companies’ end (or beginning) of the financial year falling on either sides of the enforcement date of the revised standards, and often allowing the possibility to comply with the revised standard earlier than the starting enforcement date.

Thirdly, the more the annual report is used for wider communication purposes, the more the companies’ directors choose to include information aimed at distinguishing their report from those of other companies. Other reasons lie on the different versions of the standards endorsed in different world regions; chiefly the European Union’s (EU) carve outs of the IAS 39, whereby certain provisions that refer to the treatment and reporting of certain financial instruments is different in the EU than in the rest of the world.

Finally, the format of the annual reports has been affected more and more by the possibility of using information technology tools to communicate the financial statements and all the other contents of the annual report. Some examples of how this affects the reporting can be easily found on the internet: see in particular BMW’s3 and Marks & Spencer’s4 official web pages’ investor relations areas. In these examples you can see a technological interpretation of the principle of fairness in the presentation of the statements, as the hyperlink to Excel enables the readers of the accounts to carry out their analysis more easily and efficiently than if they had to copy the relevant figures in their own spreadsheets.

These and other examples also show how the medium of communication can be used to convey the innovation strive of the entity originating the accounts. I suggest that you browse a number of annual reports of reporting entities on which you feel interested; think of the companies whose brands you know or those whose products or policies you either particularly like or dislike. You can easily download these annual reports from the companies’ respective web pages or obtain free paper versions by contacting their headquarters. You should aim at familiarising yourself with these documents and try to understand as much as you can from the narrative parts and from the financial statements parts.

You should be aware that with the expressions “IFRS” and “IAS” it is normally intended to refer to

the whole body of standards that are under the names of International Accounting Standards (IAS) and the newer International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). Many IAS are still valid insofar they have not been replaced by new IFRS. When the International Accounting Standard Board intervenes in the body of accounting standards it:

either modifies existing IAS or IFRS

- or issues new standards (IFRS), which are added to the existing list of standards superseding existing IAS, which are then no longer used

- or issues new standards (IFRS), which address completely new areas of accounting.

This is the reason why both IAS and IFRS are coexisting and make, together, the whole body of international accounting standards .

The annual reports under the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS)

Annual reports produced under the IFRS normally include, among others, some or all of the following documents:

- Chairman’s letter to the shareholders

- Operational review

- Directors’ report: business review

- Directors’ report: corporate governance

Financial statements:

- Accounting policies

- Income statement

- Balance sheet

- Cash flow statement

- Statement of changes in equity

- Notes to the accounts

- Auditors’ report

All of these documents must be read and analysed in combination. The financial statements, on their own, are able to convey only a certain level of information; even considering the amount of disclosure included in the accounting policies and the notes to the accounts, interpretation of the figures included in the statements must be supported by the analysis of the intentions of the directors and their considerations on the entity’s going concern.

For example the operational review should normally enlighten the reader of the accounts on the reasons behind certain capital expenditures, i.e. investments for maintaining or improving the production and distribution capacity of the entity. These expenses could, for example, seem inexplicably high, in comparison with sector’s or competitors’ benchmarks, if not seen in the context provided by an operational review, where the directors explain that they are undertaking a business reengineering process aimed at reducing areas of inefficiency in production or distribution.

Another example is where the strategic considerations provided by the directors in their business review enlighten about, for instance, a sudden expansion of the production volumes with lower gross margin percent; in the context of a highly price competitive environment and with a choice of aggressive market penetration, these results might reflect a sound strategy.

What you should expect to see in each of the sections above mentioned is briefly explained below. The Chairman’s letter to the shareholders is a document from the person, who should bring to the owners of the entity some relatively independent view about its situation and performance. This letter is meant to represent the chairman’s opinion and his/her view, i.e. you should not expect objectivity and perhaps even its absolute fairness can, under certain circumstances, be forgone. However, you should assume that the contents of the letter are true and based on true results, i.e. in compliance with one leg of the main accounting principle of truth and fairness.

The Operational review widely varies in formats and approaches from industry to industry and from entity to entity. You can normally expect some description of the main product lines and services provided by the entity; their contribution to the overall performance of the entity; the operational point of view of the main innovations embraced during the year. This review often makes references to the results as presented by segments according to the segmental analysis.

The Directors’ report is often split in business review and corporate governance. The business review part of the directors’ report consists of the analysis and view of the directors on the situation and performance of the entity, as a result of their decisions in the past year. Also, this document contains a prospective view of where the entity is heading; the directors’ view of the entity’s going concern. The entity’s strategy is explained in the context of its competitive market, often with a very dynamic approach encompassing the possible medium and long term scenarios of the broader industry.

Together with the operational review, this report is the main tool the directors can use to convey the image of the entity and the strength of their strategy. It is the opportunity to link the entity’s mission statement with the directors’ strategic plans, support them with the directors’ insight of the relevant environment and with their highlights of the results obtained so far. As per the chairman’s statement, this part of the report must be based on true figures and results, but it is very much a subjective interpretation of them, made by those who are at the helm of the entity (and wish to be confirmed in their roles).

The Directors’ report more and more often includes a section on Corporate Governance. This is where the directors explain what “process of supervision and control intended to ensure that the entity’s management acts in accordance with the interests of shareholders”8 is in place.

The message conveyed by this part of the report is aimed at reassuring the investors and the wider public, that the entity’s management is bound to certain rules of sound management in the interest of the shareholders and, often, also that the entity has commitments to preserve the business and natural environment in which it operates.

This information is relevant to the entity’s providers of capital in two ways: firstly it reassures them about the protection they have against the moral hazard temptation of their ‘agents’, i.e. the entity’s management; secondly it reduces the perceived risk the market attaches to the entity, which implies a reduction of the risk premium required by providers of capital of the entity, hence reducing the entity’s cost of capital.

The following chapters of this study guide will address in more details the financial statements oneby- one. It is, however, worth highlighting at this stage what you should expect to read in the Accounting policies of section. This is a section filled of ‘obvious’ material, i.e. many of the policies are in fact dictated by the IFRS and do not leave much room for interpretation. However, there are many notable exceptions, where the corporate policies reflect subjective choices of the directors, which can affect the readers’ perception of the validity and reliability of the accounts.

The Notes to the accounts are considered integral part of the financial statements and represent explanatory remarks about how certain figures and values have been obtained and what they represent in more details than it is possible to show on the face of the accounts, i.e. balance sheet, income statements, cash flow statements and statement of changes in equity. These notes often include information that is mandatorily required along side with information provided to fulfil the broader principle of fairness in the representation of the financial situation and performance of the entity. Finally the Auditors’ report represents the opinion that the auditors have stated about the validity of the accounts and their compliance with the relevant IFRS and local legislation.

Balance sheet: its contents and informational aims

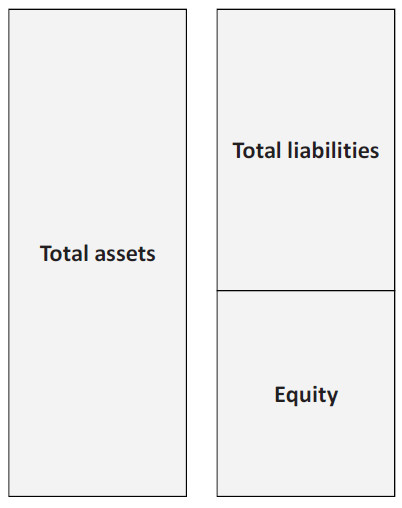

The balance sheet reports the financial situation of an entity, by showing its assets, liabilities and equity, where the equity equals the difference between total assets and total liabilities, as illustrated in figure 2.

Figure 2 - the main components of the balance sheet and their relationship

Assets: definition, classification, valuation

As a general rule, the assets are all those items over which the entity exercises enough control to enable it to receive the benefits emanating from them. A more technical definition goes along the lines of assets being entity’s rights to future economic benefits. In addition, for the assets to be reported in the balance sheet, they must be measurable in a fairly objective way. The economic benefit should be exclusive of the entity, i.e. is not emanating from a public good.

The assets are normally owned by the entity that reports them, however, it is common that non-owned assets are reported in the balance sheet, if the entity can exercise enough control over them. This is the result of the application of a principle (called substance over form), whereby the substantial truth is more relevant than the formal reality, e.g. an asset is considered as if it was owned, if is going to be used exclusively and for most of its useful life by one entity under an agreement (normally called leasing), with the third party that legally owns the asset, that payments should be made to the owner of the asset, which amount to a total that is substantially equal or higher than the value of the asset.

Classification

All assets are classified as non-current and current assets. The non-current, also called fixed assets, are assets whose economic benefits are expected to emanate to the entity in more than one go and, normally, over a period of time longer than one year. Typically, these are: machinery, property, equipment, vehicles, software, patents, licences, right to exploit others’ intellectual property or to use others’ brands, investments etc. You will also find less obvious non-current assets, such as capitalised costs, pension related items and others.

For example, capitalised costs refer to expenses that were incurred by the entity for the development of products, ideas, formulae, etc. from which revenues will be obtained in the future, but have not been obtained as yet. This refers to the time matching principle, which we will explore later on when focussing on the income statement. Pension related items refer to investments that the entity has made, in order to be able to face its obligations towards its employees, when the respective pension payments fall due.

For each of these and any other noncurrent assets, you should always refer to the definition of non-current asset and try to devise in what sense their economic benefit will flow to the entity in more than one occasion over a period of time longer than one year. A very good help for this interpretation is often represented by the notes to the accounts.

The current assets, instead, are expected to be used only once, as they will exhaust all of their economic benefit in one go. Typically, these are:

- inventories, i.e. row materials, finished goods, components;

- debtors, i.e. rights to receive cash from clients and customers or any other third party;

- cash, etc.

You will also find other less obvious items, classified as current assets. For example, prepayments refer to the entity’s right to receive services or goods for which payment has been already made. Once again, however, these are current assets as their economic benefit will flow to the entity in one go and anyway within one year. The notes to the accounts can represent a valuable help also for the interpretation of these items.

Valuation

The default criterion that concerns the assets values, as you read them on the face of the balance sheet, is that the values should represent prudent valuations of the future economic benefits that are expected to emanate from the assets to the entity, under the assumption of going concern, i.e. the assumption that the entity will keep operating in the foreseeable future.

To this respect, three important considerations must be made:

- firstly, the assumption is made that, as a starting point, the original cost of the assets when they were purchased, or indeed produced in-house, is a conservative and objective, hence appropriate, valuation of the assets (historical cost valuation);

- secondly, exceptions must be made in the case of current assets, and more specifically inventories, when their expected realisable value is lower than their cost of purchase or production;

- and thirdly, a different method, called fair value accounting, is required (or allowed) under certain circumstances for certain assets.

The historical cost valuation has the following implications for you, when you read the balance sheet of an entity. Assets reported using this method (and these are the vast majority of the non-current assets) are reported at a value that is calculated as their cost of purchase or production:

- less the sum of the deductions regularly and methodically made every year to represent theamount of their economic benefits that has emanated to the entity - these deductions arecalled depreciation for tangible assets and amortisation for intangible assets

- less any further loss in value that is not represented by the regular deduction above explained,which result from exceptional, unexpected, permanent and unfavourable changes in theamount of future economic benefits still left to emanate to the entity, for example because ofdamages, or unexpected technological obsolescence, or shorter than originally accounted foruseful life - these deductions are called impairments

- plus any increase in value that results from exceptional, unexpected, permanent, favourableand allowed to be reported changes in the amount of future economic benefits still left toemanate to the entity, for example because of permanent changes of the marketability of thoseassets, such as is the case of increases in value of properties (not in the context of a financialcrisis) - these increases in values are called revaluations.

All the values and their changes as explained in the bullet point above can be easily traced in the notes to the accounts of your chosen entity. Look at its balance sheet, find the non-current (or fixed) assets, identify the notes to the accounts that refer to them; in those notes you will find a table with an explanation of the changes in the historical costs of those assets, due to acquisitions and disposal, split in categories, which vary according to the industry and to the entity, typical examples being machinery, fixture and fittings, properties, vehicles, equipment, etc. Also, based on the same categories, you will find the changes in value of the sum of the depreciation and amortisation, the impairments and the revaluations.

Whilst the notes to the accounts refer to the facts of the entity’s past years, you will find explanations about the policies adopted by the entity in the accounting policies, where the depreciation and amortisation policies are explained, together with the impairment and revaluation criteria. These policies are normally shown in a section of the annual report that just precedes or just follows the financial statements or are included in the notes to the accounts as the first note.

Fair value accounting is applied to financial instruments and can be applied to other non-current assets. The underlying rationale of fair value accounting is that, where it is possible to refer to a market value for certain assets, that one is the most appropriate value for reporting purposes. Where no market value is available, then reference should be made to recent transactions involving similar items. In absence of these transactions, other techniques should be used, which are aimed at calculating the actual amount of economic benefit that will emanate from these assets.

Whilst the intention of this method of accounting is to provide the reader of the accounts with more realistic figures, which are updated at each period end (in the annual report or in the interim reports), the effect has also been to bring the volatility of market values and the uncertainty of valuation techniques to the balance sheet (and to an extent to the income statement, as we will address later on). The implications of fair value accounting, for you when you read the accounts of your chosen entity, are that the values of any investment or other financial instruments present in the balance sheet are likely to refer to their respective market quotations as known when the accounts you are reading were prepared.

On this matter, though, you must be aware of recent developments due to the international financial crisis and on-going recession; a temporarily provision has been hastily taken by the International Accounting Standard Board, to ‘relax’ the fair value accounting rules. The rationale behind this provision is that, in a context of widespread financial crisis and recession, reporting corporate investments at their market values negatively affects the value of corporate equity and, as this equity is likely to represent investments of other entities, also these other entities’ equities are negatively affected, triggering a destructive domino effect that contributes to spread panic among investors and deepens the crisis even further.

It is not obvious, at the moment, how long the fair value accounting rules will stay relaxed or whether they will ever be restored in their original form. Given the controversy that has accompanied these rules all along since they have been issued, it is very likely that those who have never been convinced by this approach will leverage on the current situation to radically modify it. For what concerns the current assets, again the default criterion of valuation at cost applies, where possible i.e., as mentioned above, inventories are valued at their cost unless their net realisable value is expected to be lower.

Cash, debtors and pre-payments are valued at their nominal value, less any prudent forecast of losses from those values, e.g. expected percentage of debts that will not be honoured by the pool of debtors or the value of debts owed by debtors who are expected to default. Other investments are valued either at their cost or at their fair value.

Liabilities: definition, classification, valuation

Liabilities are entity’s obligations to transfer future economic benefits to third parties. They comprise: all debentures, borrowings from lenders, received bills and unpaid invoices, which are actual obligations; but also, accruals, which are obligations not yet substantiated by third parties’ invoices or bills; and provisions for future expenses, which are not yet obligations, but will be in the future for facts that have happened in the past.

A few examples of the above mentioned liabilities follow. Debentures are mostly made of bonds, also called own debt instruments. Borrowings are short and long term loans, mortgages and overdrafts. Bills and invoices are documents received from providers of services and suppliers of goods who were not paid as yet when the accounts were closed. Accruals are obligations for services or goods that have been received, but whose bills and invoices have not been produced or received yet, e.g. rent, workforce, consultancies, raw materials.

Provisions for future expenses are undefined commitments that the entity is certain or likely to have to honour in the future and which will, normally, be valued more exactly in the future, e.g. the costs of a legal case that is likely to be lost, the costs of decommissioning a field when the on-going extraction of minerals will reach an end.

Classification

Liabilities are classified according to when they are likely to fall due, i.e. within a year or in more than a year, as current and long term liabilities respectively. You will find provisions under either of the two categories according to when they are expected to become real.

Often you will find that the same long term obligation has also a short term leg, as it is the case of mortgages, for the principal components falling due within a year, debentures, for the bonds reaching their maturity within a year, etc.

Valuation

Liabilities are valued according to the expected value of the economic benefits that the entity will have to transfer to third parties, in order to settle the underlying obligations. This means that the value you see in the balance sheet for each item of liability or provision represents a prudent valuation of how much the entity is likely to have to pay when the obligation will fall due, this being the result of a statistical calculation weighting the probabilities of possible outcomes of series of events or simply an estimate of the likely payment that the entity might be required to make.

An example of the first is a provision for the cost of replacement or repair of faulty products covered by guarantee, whereby the entity can estimate the expected number of products that will be returned under the terms of the guarantee and hence calculate the cost of replace or repair them. An example of the second is a provision for a case in court, whereby it is known that the entity will succumb and an estimate is made of the most likely (and prudent) amount that will have to be paid.

More common examples, though, are the liabilities towards suppliers and providers, which are reported at their nominal value, unless it is likely that only part of the total amount will have to be eventually paid. Another typical liability item you will come across is deferred taxation. This occurs when the entity had been previously allowed to postpone the payment of its taxes, which created a liability to be paid in future years. Once again, this liability is likely to have a short term leg that reflects the amounts that are falling due in the next year.

You might also come across the liability component of a hybrid financial instrument. This is the case of your chosen entity having issued, for example, convertible bonds.14 In compliance with IAS, these instruments are reported splitting the debt component, as if the bond was an ordinary one, and the equity component, which is the embedded ‘call option’, i.e. the option to buy a share at a fixed price in the future.

See appendix B for an example of this calculation. For any other liability that you find in the balance sheet of your chosen entity, it is advisable to read the respective notes to the accounts, for explanations.

Equity: value, meaning, components

Value and its meaning

The value of the equity is the result of total assets less total liabilities. It represents the ‘book value’ of the entity, i.e. its value according to the accounting books, which has a very weak link with the value attributed to it by actual and potential investors. The equity is normally a positive value. A negative equity is not sustainable in the long run, hence, in such case, an entity’s management will have to either raise more capital by issuing new shares or wind up the entity.

Ultimately the equity , being the excess of assets over liabilities, represents the amount of capital that, according to the books, guarantees an entity’s solvency in case of winding up. However, given the definition of assets and their valuation criteria, it is apparent that a positive equity might, in fact, become negative in the very moment when the entity is being wound up. This is the effect of the going concern assumption fading away and the assets being, therefore, valued at their realisable value as opposed to their potential contribution to the entity in operation.

Components

Not only the total value of the equity, but also its components convey valuable information for the readers of the accounts. The main message you want to obtain from the analysis of the components of the equity is what part of it is made of realised profits, the remaining part being made of recognised (but not realised) profits. Realised profits are values calculated yearly, and accumulated year on year, as the excess of revenues over expenses. We will address this concept in the next chapter on income statement, however it is worth knowing that only the profits that have been realised can be distributed to the shareholders as dividends, whilst non-realised profits cannot be distributed.

The rationale underpinning this rule is that only realised profits objectively represent value added to the entity’s wealth, as they are the result of transactions with third parties. Recognised profits, instead, are the results of assumptions which, no matter how much they have been substantiated by sophisticated procedures and credible and certified experts, they still remain assumptions.

Typically the equity includes the following:

- Share capital, which represents the nominal value of all the shares issued by the entity

- Share premium reserve, which represents the accumulated value of all premia paid by new shareholders as they bought shares at higher than their nominal values

- Retained profits, or reserve of profits, which represent the accumulated profits that have beenretained in the entity over its whole life. This value is often split in more reserves, called other statutory reserves

- Retained profit or loss, which represents the retained profit or the loss of the current year

- Revaluation reserve, which represents the sum of all the recognised increases in value of noncurrentassets over the whole life of the entity

- Gains and losses that have been accounted for directly in the equity, as opposed to havingbeen included in the profit, i.e. not reported in the income statement. These are technicalreserves made from the changes in value of financial instruments under certain circumstances or changes in value of other assets or liabilities due to changes in the rate of exchangebetween the currency used for the accounts and other denomination currencies of credits,debts and other items.

You might come across other components of the equity, which are less significant and for which some explanation is likely to be given in the notes to the accounts.

Overall informational value of the balance sheet

The balance sheet provides you with an insight about how much capital the entity’s management can count on or, in more appropriate terms, the total value of the assets, which the management can employ to operate the business, and what these assets are. On the other hand, the balance sheet also indicates where the capital to finance these assets has come from; liabilities represent capital that is borrowed by the entity and equity represents capital that is owned by the entity. The capital coming from both liabilities and equity is invested in the entity’s assets.

Hence, the accounting equation that underpins the balance sheet can be read with two perspectives:

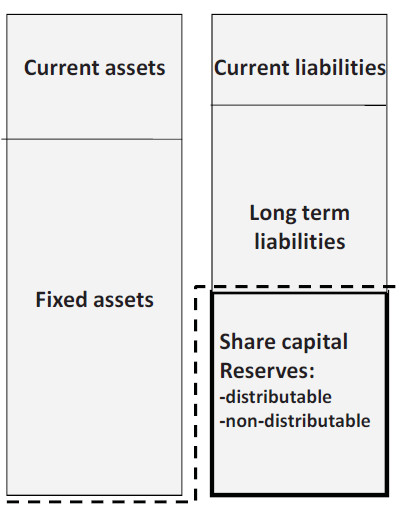

- the first is “Total assets - total liabilities = equity”, which highlights the message of thebalance sheet that the equity is the excess of assets over liabilities, making the equity theentity’s ‘net book value’, i.e. the entity’s value, as reported in the books kept according toaccounting rules, net of all liabilities (see section 3.3. above and figure 3)

Figure 3 - the accounting equation as “Total assets - total liabilities = equity”

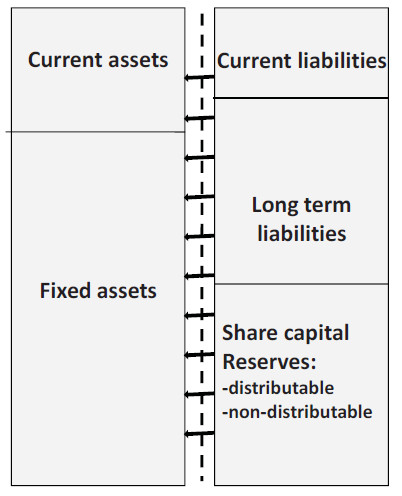

- the second is “Total assets = total liabilities + equity”, which highlights the message thatall assets must be financed by capital raised either through debt, i.e. liabilities, or throughowner’s investment, i.e. equity. (See figure 4)

Figure 4 - the accounting equation as “Total assets = total liabilities + equity”

Income statement: various levels of profit and informational aims

The income statement shows the entity’s performance in terms of profits, i.e. how the entity has transformed inputs in more valuable (when the profits are positive) outputs.

Gross profit

The first profit you might come across, when reading the income statement of your chosen entity (you can refer again to the annual reports indicated in chapter 1 - Introduction) is the gross profit. This profit shows the value that the entity has added to the value of the inputs that the entity has used to produce what has been sold. The equation for gross profit is:

Turnover - cost of sales = gross profit Where:

- turnover is the value recognised by the entity’s clients and customers for the productionthat has been sold. Turnover is also called revenues, sale revenues, sales

- cost of sales or cost of goods sold is the cost of production of what has been sold. Thismeans that the costs of what has been produced but not sold are not included in here nor,indeed, anywhere else in the income statement.

Hence, gross profit represents the ability of the entity to make its clients and consumers recognise a value for its products or services, which is higher than the cost of producing them. You can expect a comparatively15 high gross profit, from entities whose brand is renown as one of high quality, and a comparatively low gross profit, from entities whose brand is unknown or known as one of low price products or services.

Gross profit is not always shown on the face of the accounts, i.e. in the page of the income statement, but is often shown in the notes to the accounts that refer to the next line down of the income statement, i.e. the operating profit. Certain entities choose not to show the gross profit; this is allowed by the IFRS/IAS and is particularly obvious in businesses where gross and operating profits are difficult to separate. The reasons for this occurrence will be explained below, in the section on operating profit.

Operating profit and profit before interest and tax

The operating profit results from deducting from the gross profit further expenses and adding any operating income that was not included in the turnover. These are called, respectively, other operating expenses and other operating income. The former represents:

- administrative expenses,i.e. the costs of running the personnel office, the accounting department, the costs of legal advice, etc.;

- distribution costs, i.e. those related to marketing, transport of finished goods, promotion, etc.

Other operating income includes any income that comes from the operations of the entity, i.e. from producing, buying, selling, licensing third parties to use patents, brands, logos, etc. but is not originated by the entity’s core business. Other operating expenses and income can originate also from exceptional items, i.e. as the result of events that are exceptional by nature or size.

For example profit or loss deriving from disposal of noncurrent assets is an exceptional item by nature, given that the entity is not normally disposing of its non-current assets, it is instead using them for production purposes. Also, profit deriving from an order of exceptional size, albeit of typical nature, is an exceptional item. The income and expenses deriving from the exceptional items can also be shown separately, below the operating profit; this choice is allowed by the IAS/IFRS.

As mentioned in the section above on gross profit, in certain entities, typically in service industries, all operating expenses are incurred on as part of running the core business; often there is no distinction between cost of sales and other operating expenses. For example, in airlines, it is difficult to draw a line that separates the administrative and distribution costs related to issuing a ticket (or processing an electronic booking) and the cost of sale of the same ticket.

What about the check-in operations? Are they simply enabling the production of the main service of transporting passengers or are they part of the actual production of the service? Browse the British Airways latest annual report16 to find out how this entity has solved the problem of reporting its performance. As you will see, a list of the major categories of costs is presented with no distinction of what is cost of sales and what is other operating expenses, but with a useful level of detail.

Profit before interest and tax represents the profit made by the entity from anything but financial income and costs. In other terms, below this line you will find other income related to financial investments, i.e. mainly interest, as well as other costs related to borrowing, i.e. once again mainly interest - unless the entity is operating in the banking sector, where of course interest payable and earned are part of the core business.

Only in case the exceptional items have been shown separately, you will find that profit before interest and tax and operating profit show two different values. If the two values are the same, chances are that you will not see both reported (what would the point be?). This might confuse you, when you compare two or more entities, where one reports an operating profit and the others report a profit before interest tax, but they all might refer to the same concept.

However the layout is arranged, the operating profit is a key value for the evaluation of the performance of a reporting entity in that it represents the profit that the entity has been able to create from its operations (including or not including exceptional items and with separate consideration of the discontinued operations, if it is the case). The operations are at the core of the entity’s business and, where the operations provide a healthy profit, the entity is achieving one of its main targets, i.e. produce wealth. In this case, whether this wealth actually reaches the owners, making the entity fulfil its main reason of existence, depends no longer on the entity’s operations but on how it is financed, given that the only remaining cost to be deducted from the profit before interest and tax, is the cost related to the financing of the entity.

This is the reason why, when analysing the performance of the entity, it will be important to devise, in the context of the specific analysis, whether it is appropriate to consider or to exclude exceptional items or the discontinued operations, depending on whether the analysis aims at evaluating the performance of the specific period under consideration or is more focussed on the underlying performance of the entity. More on this matter will be considered in the next chapters of this guide.

Profit after tax and retained profit

Profit after tax results from deducting tax from the profit before interest and tax. The deducted tax is the amount of taxation calculated from the profit before interest and tax, regardless of any public policy that, as it happens, allows postponing the payment in certain circumstances. This form of profit is also called profit attributable to the shareholders, meaning that the owners are entitled to that value created by the entity; part of this profit will reach the owners directly, when dividends are paid out, the remaining will be reinvested in the entity itself, becoming retained profit that goes to feed the equity.

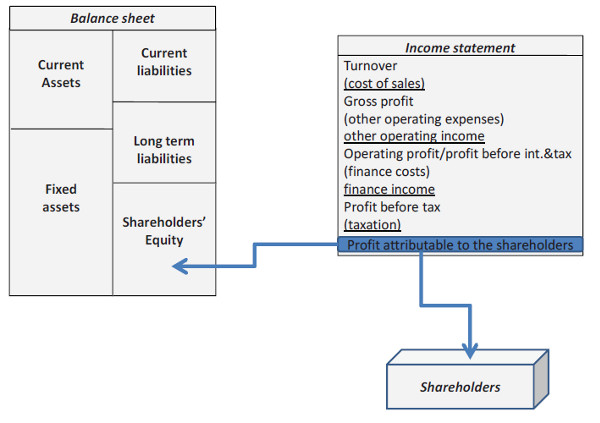

As the shareholders’ equity represents the book value of the entity, the owners see their capital increase in value by the retained profit, which is a distributable reserve of the shareholders’ equity - as illustrated in figure 5.

Figure 5 - the allocation of profit attributable to the shareholders

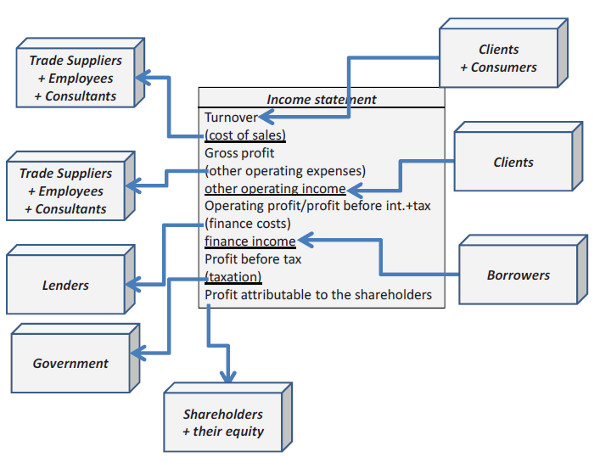

In broader terms you can look at the income statement as the valuation of the allocation of the wealth, originated by the operating and financial income, to various different parties, which are the entity itself, suppliers of materials and services, employees, providers of credit capital and providers of equity capital - as illustrated in figure 6.

Figure 6 - the origins and destination of income

Cash flow statement: its contents and informational aims

The cash flow statement shows the entity’s performance in terms of cash flows, i.e. from where the

cash inflows have come and to where the cash outflows have gone. The cash flow statement is divided in three parts: cash from operating activities, cash from investing activities, cash from financing activities. Cash from operating activities is made of cash outflows, spent to run the reporting entity’s core operations, e.g. paying trade creditors, paying workforce, bills and consultants; and cash inflows, deriving from selling the products or services typical of the reporting entity.

Cash from investing activities is made of cash outflows spent to purchase non-current assets and cash inflows deriving from disposing of those assets. Cash from financing activities is made of cash inflows deriving from obtaining loans and other credit, and cash outflows spent to repay those debts.

Each of the three parts can show a net cash inflow or a net cash outflow as a result, respectively if the cash inflows of those activities are higher or lower than the cash outflows. However, it is typical for an entity that the operating activities show a positive net cash flow, the investing activities result in a negative net cash flow and the financing activities result in a negative net cash flow.

This typical situation is the scenario of an entity that is creating more cash than it uses for running its core operations, uses cash to maintain and perhaps expand its assets and uses cash to pay back its lenders. Other scenarios are made of the various possible combinations of positive and negative results. For example in the year when an entity has borrowed a substantial amount of money, the cash from financing activities is likely to be a positive figure. The meaning is that in that year the entity might

have improved its liquidity position, by borrowing more money; in the years to come that money must be returned to the lenders, hence the cash from financing activities will show a reverse effect, i.e. it will contribute to deplete the cash resources of the reporting entity.

Again, you might come across entities that report a positive cash flow from investing activities. This is typically due to the entity disposing of non-current assets, i.e. properties plant and equipment or financial assets or indeed intangible assets. Regardless whether or not the entity has made a gain out of the disposal, i.e. whether or not it has sold the asset at a higher value than its net book value, as long as it has sold the asset for a price, a positive cash flow is derived from that disposal.

These examples should lead to a reflection about the difference between cash and economic performance. The latter example, taken to the extreme, leads to a reporting entity that can potentially become cash rich in the short term, but that is depleting its capital assets, compromising its capacity to produce profits in the medium and long term.

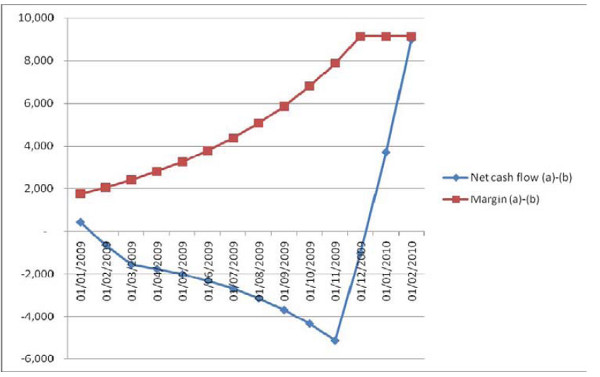

On the other hand, you might come across reporting entities whose fast paced expansion absorbs more liquidity than it produces, despite being profitable. A worked example is reported in appendix C, where the case of fictitious consulting company called Consulando is presented. Consulando

expands at such a fast pace that every month it needs larger amounts of cash to pay for the services it provides to ever more clients, whilst the amounts of cash that it receives from the clients served in the previous months is never sufficient to cover for the current needs. Once Consulando will stop

expanding, the cash inflows will catch up with the cash outflows and the business profitability will be reflected also in accumulation of cash, as illustrated in figure 6. The peril is, of course, that before Consulando has saturated the entire demand that it potentially can, its managers decide or are forced to slow down the expansion, because of lack of access to immediate cash.

Figure 6 - the cash flow and the margin trends of Consulando compared - see appendix C for calculations and assumptions.

If Consulando were to close its accounts on 31st August 2009, its cash flow statement would show a negative cash flow from operations most likely compensated by a positive cash flow from financing activities or, if the reporting entity was cash rich from previous activities, the negative cash flow from operations would most likely not need to be compensated by financing activities and the net change in cash at the end of the year would be negative. In this scenario, drawing a conclusion that Consulando is not performing well would be wrong.