Purchasing strategies and Supplier Selection

- Details

- Category: Supply Chain Management

- Hits: 25,481

Strategic Role of Purchasing

Purchasing function has a strategically indispensable role to play in supply chain management. It covers the sourcing end of supply chain management interfacing with the delivery end of the suppliers.

The classical definition of purchasing is: to obtain materials and/or services of the right quality in the right quantity from the right source, deliver them to the right place at the right price.

The composite definition of purchasing is : the process undertaken by the organisational unit which, either as a function or as part of an integrated supply chain, is responsible for procuring supplies of materials and services of the right quality, quantity, time and price, and the management of the suppliers, thereby contributing to the competitive advantages of the achievement of the corporate strategy.

Purchasing management thus, by definition, supports and implements the supply chain management strategies. It is one of, or maybe the most important, delivery arms of supply chain management. Often it directly delivers the cost-saving, quality improvement and fulfills the supplier relationships. Purchasing function’s critical role can also be illustrated from a simplified income statement:

| Total sales | = | £10,000,000 |

| Purchased Service/materials | = | £7,000,000 |

| Salaries | = | £2,000,000 |

| Overheads | = | £500,000 |

| Profit | = | £500,000 |

Suppose this is a company’s profit-loss account for the current year, and the shareholders demand the CEO to deliver double the profit in the next year. What can the CEO do with regards to those factors associated with the account? Well, assume everything else remains equal, doubling the total sales will eventually double the profit. It is equivalent to create two companies.

But the problem with this approach is that the sales volume is often constrained by the market. If the product cycle has passed the maturity and started to decline, to maintain the amount of sale would be difficult let alone to double it. Or, the company could reduce the salary by 25%, which could make £500,000 saving for the bottom line. Common sense tells that it is not feasible, and the CEO would not agree as his 25% cut would be biggest of all. Another alternative is to get rid of all the overheads costs, which also makes £500,000 saving. However, this is almost impossible to do practically, nor agreeable theoretically.

What’s left is to curtail the buyer-in goods and service by 7% which will make $500,000 savings for the bottom line. Now, just 7% cut in purchasing would result in 100% increase of profit. This is no doubt a very effective approach as the effort appears to be small and the gain is amazingly high. It is apparently the only viable and convincing choice there is to it. Who is going to do that for the company? It is the purchasing function.

This is why purchasing function is distinctly so important to the company’s profit level. It is the company’s profit leveraging point, whereby a small input can generate large output. No wonder we see many OEMs often try to enforce the supplied material cost reduction by 4-5% year on year, albeit, this may not be the best approach from the contemporary supply chain best-practice perspective.

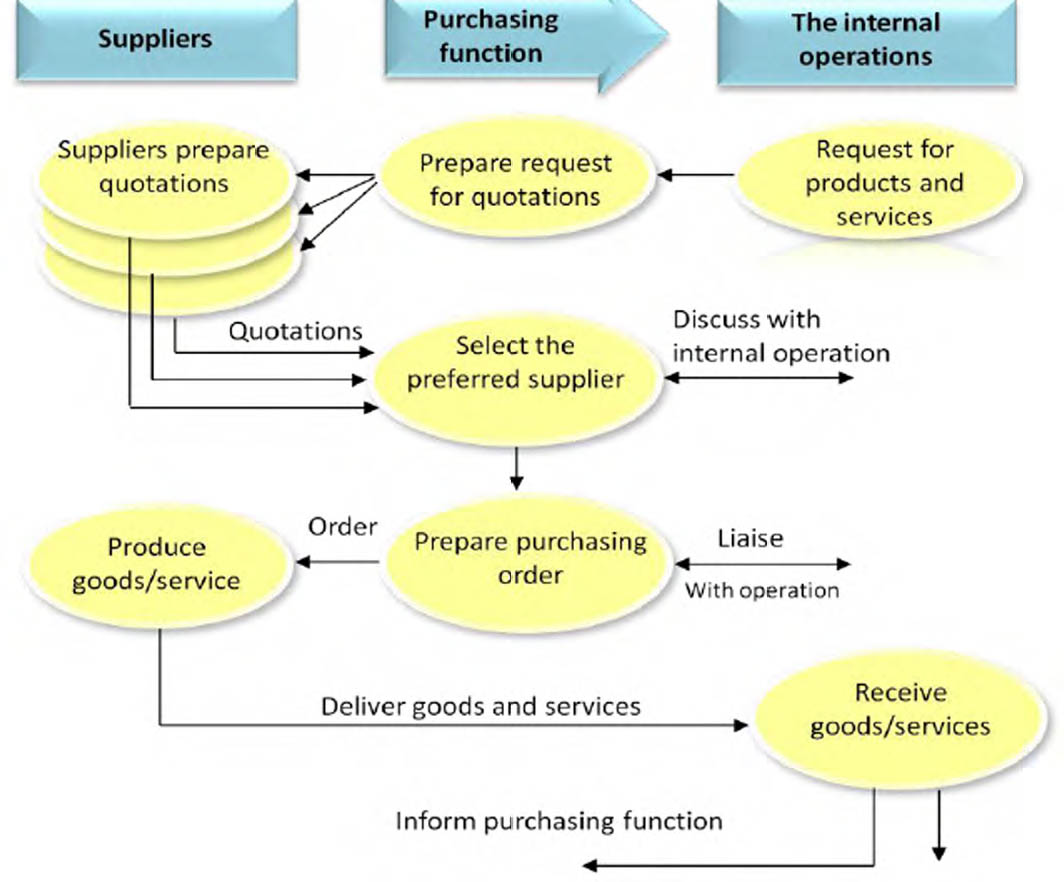

The operational processes of purchasing function can be represented by the diagram shown in Figure x. It basically intermediates the company’s internal operations with the suppliers, ensuring the right suppliers are found and engaged in a process of supply and delivering the required materials, components and services that best suit the internal operations.

Figure 30. Operational purchasing activities

These are just the visible parts of the purchasing function. Beyond these processes, there might more important high-level strategic decisions to be made for the purchasing, through the purchasing and by the purchasing. Typically, make-or-buy decisions, supply base rationalization, supplier development and etc..

Purchasing Portfolio

“What is the best way to managing purchasing?” “What is the best strategy for purchasing and supply?” Many practitioners and academics have asking these questions in past and still today. In fact, there were no shortages of answers to these questions in the plethora of literatures even in the early years. But few stood the test of time for its applicability and universality.

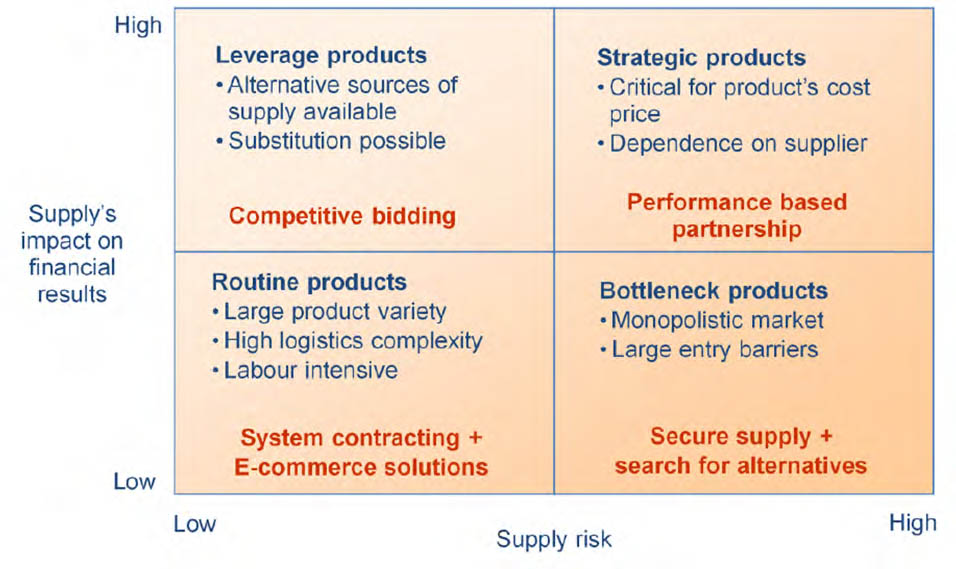

Then there came Dr.Peter Kraljic from McKinsey who claimed that there is no single best way existed for managing purchasing in all circumstances. He then published a paper entitled “Purchasing Must Become Supply Management” in Harvard Business Review in September 1983, and proposed the very well known Kraljic Purchasing Portfolio model (see figure x). This model had since then been widely cited and referenced across the world in all types of management literatures. There are now many modified versions by many scholars who have contributed and further developed the application of this model.

Figure 31. Kraljic purchasing portfolio matrix

Dr. Kraljic’s answer to the question can be paraphrased as that although there is no single best way, but if we know which product category we are purchasing, there would be the best way to do the purchasing for this product category. He looked in two dimensions to categorize all the purchased products. One is the supply risk of the product from the market; two is the financial impact of the purchased material. Thus a four categories matrix emerged presenting four different types of the purchased products.

Leverage products

Leverage products are those you buy from your supplier that will have a significant impact on the finance of your own final product, but it is relatively easy to buy from the supply market, hence low market risk. For example, wood is a leveraged product for wood furniture manufacturers to purchase. This is because most of the furniture they do are made of wood. A large portion of the cost comes from wood price and the furniture prices are dependent on the wood cost in the market place. However, unless it is rare wood which they hardly use, the supply of wood is plentiful and there is very low risk of short supply.

For such leverage products, Kraljic proposes a purchasing strategy of competitive bidding. Understandably, competitive bidding will only work if there is more than one supplier. The low supply risk factor of leverage products supports this strategy. Alternative suppliers are in this case available and substitution of supplier is possible. The buyer can then benefit on the lower price and cost advantages. It is important to understand that the buyer needs to do so, because the high financial impact the leveraged products.

Routine Products

Routine products are those materials that have a very little financial impact on the buyer’s own products and also there are plenty to choose from in the market place. Examples of these products or materials are small fixtures, pant, and standard components like springs and nuts. They don’t cost much in comparison to the total cost of your own products. The market availability for those materials is very high and there is no risk of supply.

For the routine products, Kraljic proposed a purchasing strategy of system contracting plus e-commerce solutions, because these products have large varieties and high logistics complexity and often labor-intensive in handling. The sophisticated computer-based system ordering suits well with the nature of the products. Although the alternative sources of supply are available, bidding is not recommended. This is because the low-cost nature of the materials made the bidding unnecessary, and the variety complexity of the materials will make the bidding unaffordable.

Strategic Products

Strategic products are those components have a high level of the financial impact on your final product. They are very expansive to develop and manufacture, and often involve high technology contents. They are not usually available in the market place, thus high supply risk. The buyer will need to contract for the manufacturing rather than pay for the delivery. The examples of these products are engines for automobile and compressor for the refrigerator.

For the strategic products, Kraljic proposed a purchasing strategy of performance-based partnership. That is to create a partnership relation with the supplier and work together to develop and manufacture the components. The proposal is obviously for good reasons. This type of components usually is not made to stock it at lease needs to be ordered to the specific requirement, often the components will have to be designed and developed together with the supplier. Hence, strictly speaking, it is no longer the purchasing of products, but rather purchasing of the developing and manufacturing capabilities from the suppliers. That’s why ‘performance-based’ is necessary because it is about capability.

Bottleneck products

Bottleneck products are those components that may or may not cost too much in comparison with the total material cost, but they must have them and they are very difficult to get hold of. The supply risk for those components is high, and the availability of the components is not guaranteed.

For example, the small amount of precious metal required for the exhaust purification system is a typical bottleneck material. Without it, the automobile will not pass the environmental standard and will not be allowed on the road. There are only very few supply in the world that have the blessing of the natural resource for those precious metal. Demand is much higher than supply.

For such bottleneck products, Kraljic recommended a purchasing strategy of securing supply plus searching for alternatives. You must secure your current supply because you have no choice, you must have it; you need to search for alternatives because the constant risk of cut-throat. The alternatives include radical new designs which may use different materials that are not short of supply. This is the relationship setting that the supplier has the up-hand; buyers will have to take some diversions.

Supplier Selection

One of the mission critical tasks of purchasing function is to identify and select the suppliers. This is particularly true when we talk about of strategic components and bottleneck components. In both of these categories, suppliers are by no means ascertained. The quality of the suppliers and the righteousness of their selection will have direct implications on the supply chain’s long-term competitiveness. The processes of going about selecting suppliers can be suggested as follows, but by no means comprehensive and universal.

The processes to go about selecting the suppliers are as follows.

- Set up Selection criteria

- Initial contact

- Formal evaluation

- Price quotation

- Financial data

- Reference checking

- Supplier visit

- Audits, assessments or surveys

- Initiation test

Apparently, these processes are mainly around setting and taking measures against the criteria. However, there are three significantly different approaches toward supplier selection. The first is based on the product that the supplier can deliver.

This approach will normally check the product prototype to see if the quality and technical specifications can be met and the delivery terms are satisfactory. The second is based on the capability that the supplier displays. It typical checks whether the supplier has the design and development capability, strategic investment in technology and skills, and up to scratch management.

This capability approach is often used for long-term supplier selection and can be done well before the idea of component is taking shape. The third is the combination of product and capability selection. It applies to when a strategically important new part is to be outsourced to a new supplier. Not only the supplier must comply with all the product-specific requirements but also should have the capability of making future generation of the products in the long run, so as to sustain the supply chain development. Some frequently used criteria for capability filtering are as follows.

Assessment criteria on the supplier’s capability:

- Total quality management policy

- BS 5750/ ISO 9000 certification or equivalent

- Implementing latest techniques e.g. JIT, EDI

- In-house design capability

- Ability to supply locally or world-wide as appropriate

- Consistent delivery performance, service standards and product quality

- Attitude on total acquisition cost

- Willingness to change, flexible attitude of management and workforce

- Favorable long term investment plan

Tools for Supplier Selection

To facilitate the process of supplier selection, quantitative tools are beneficial. They can make the selection process more rationale; they serve as the platform for meaningful discussion or debate; they provide traceable documents; they form the factual contents for decision-making. Three basic quantitative tools are introduced here for managers to get started on creating their own tools for their own industry and products.

The first one is called the ‘categorical method’ as shown in figure 32. You define the selection criteria first, for example quality, delivery and service; then you make three category judgments: good (+), unsatisfactory (-), and neutral (0) against the criteria for each supplier; finally you sum up the judgment into a total score for each supplier; the highest one will be selected.

This method is very simple to apply but is rather subjective. Hence, it is recommended to form a multi-functional team to make collective judgments in order to limit the bias from individuals.

Table 32. Categorical method

| Supplier | Performance Characteristics | |||

| Quality | Delivery | Service | Total | |

| A | Good (+) | Unsatisfactory (-) | Neutral (0) | 0 |

| B | Neutral (0) | Good (+) | Good (+) | ++ |

| C | Neutral (0) | Unsatisfactory (-) | Neutral (0) | - |

The second method is called the ‘cost ratio method’ as shown in figure 33. Similarly, you set up the required criteria against alternative suppliers. What’s different from the categorical method is that it is not entirely based on people’s subjective judgment. It makes use of some available data on the quality performance; service standard and delivery reliability for instance. With those historically collected data, you will be able to establish the corresponding cost ratios for each criterion in term of how much the penalty cost needs to be added.

The original quoted unit prices from different suppliers will then be adjusted to generate the net-adjusted costs. It then becomes clear that if the supplier selection is based on the original quoted unit price, then the supplier C should be selected because its cost is the lowest. However, if the supplier selection process takes into account of the suppliers historical performances in the three areas and use the net-adjusted cost, the lowest cost supplier is A not C. The little homework of considering the cost ratio has made very different choice in the selection.

Table: Cost ratio method

| Supplier | Quality Cost Ratio (%) | Delivery Cost Ratio (%) | Service Cost Ratio (%) | Total Penalty Ratio (%) | Quoted Price/ Unit (£) | Net djusted Cost (£) |

| A | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 16.00 | 16.80 |

| B | 5 | 4 | 2 | 11 | 15.40 | 17.01 |

| C | 7 | 3 | 5 | 15 | 15.00 | 17.25 |

The problem with the two methods is that all the criteria are treated equally in the selection process. This is not really true in real-world business. People have preferences toward different criteria for various reasons. In some circumstances, quality is more important than delivery, and in other situations, the delivery is more than quality. The third method takes care of these preferences by assigning a weight to each criterion. It is called the ‘linear-average method’ as shown in figure 34.

The weight is a score that reflects the relative importance of the criterion. The sum of all the weight scores is normally 100. Whatever the judgement score multiplied by the weight becomes the adjusted judgment score; and then add all the adjusted scores together to generate the total selection score for the supplier. It should be noted that the weight can also be applied to the cost ratio method or any other method. In the end, the most appropriate supplier selection tool perhaps is the combination of some of those methods.

Table: Linear -Averaging Method

| Selection riteria | Weight | Supplier A | Supplier B | Supplier C | |||

| Score | Total | Score | Total | Score | Total | ||

| Quality | 52 | 8 | 416 | 5 | 260 | 6 | 312 |

| Delivery | 26 | 3 | 78 | 8 | 208 | 3 | 78 |

| Service | 22 | 5 | 110 | 8 | 176 | 5 | 110 |

| Total | 604 | 644 | 500 |

Towards Knowledge Based Sourcing

Purchasing practice and theory never stops developing. It really is a dynamic and evolving subject in both theory and practice. Looking back at the recent three decades of purchasing development, an evolution pattern starts to emerge. Depend on how one would like to take out of it; the pattern may be presented in different ways. Here we frame the evolution pattern into two perspectives, each of which has four key stages. The first perspective is on the operational focuses and the second perspective is mainly on the characteristics changes.

The operational focus perspective classifies the purchasing function into four stages:

- Stage one can be called Product centered purchasing. The operation is basically concentrated exclusively upon the purchasing of tangible products and its outcomes on the overall businesses. It is usually measured in the five rights (right price, right time, right quantity, right quality and from the right sources).

- Stage two can be called ‘Process centered purchasing’. It is predominantly processed focused operation. It moves beyond the direct outcomes of the purchasing activities and into the processes through which the outcomes are delivered. This means that the managers realized that the processes are the enablers, and often the controllers of the purchasing outcomes.

- Stage three can be called ‘Relational purchasing’. The focus of the operation is not just on the process but also on the inter-organizational relationships. The relationship has been taken on as the key management instrument to enhance the product quality and technological advances; it also had a massive positive impact on supplier integration and development.

- Stage four can be called ‘Performance centered purchasing’. It focuses on optimum business performances as a whole and managing the purchasing function’s contributions to the overall business performances. In this way, the purchasing function has been strategically connected to the business’s ultimate objectives and delivery. It is a system approach.

The characteristics focus perspective classifies the purchasing function into four stages:

- Stage one is ‘passive’ in character. In this stage the purchasing can be defined as lack of strategic directions and is mainly reactive to operational requirements. High proportion of purchasing manager’s time is on routine operations with low visibility to the supply chain. The supplier selection is based on price and availability only.

- Stage two is ‘independent’ in character. In this stage the purchasing may have adopted the latest technology and process, but may have not got the strategy that aligned with the competition. Links between purchasing and technical disciplines may have been established; performance based on cost reduction; top management recognises the importance of professional development and the opportunities in purchasing contributing to profitability.

- Stage three is ‘supportive’ in character. Purchasing starts to support the firm’s competitive strategy by adopting purchasing techniques and products which strengthen the firm’s competitive position. Suppliers are considered as a key competitive resource. The supply market, products evolution and suppliers capabilities are continuously monitored and analyzed.

- Stage four is ‘integrative’ in character. In this stage purchasing strategy fully integrates with the firm’s purchasing function. Multifunctional teams and cross functional training of purchasing professional begin to take hold. Open and close communication with other functional departments is hard wired into the processes. Purchasing is measured in terms of its contribution to the overall success of the firm.

It is interesting to notice that the four stages in both perspectives can be broadly matched with a little obvious impediment. However, it will take a more rigorous approach to declare the theoretical match and to create a new stage model for purchasing development. The discussion presented here merely opens the scope of discussion and hopefully, stimulate further thinking and debate.

But there is no doubt that the purchasing function has now become a much more sophisticated process and has much wider and deeper impact to the business performance. It is moving away from the short-term towards long-term; from a function to processes; from transactional to relational; from cost saving to performance enhancing.

The picture of purchasing in the future perhaps can be described as the knowledge-based purchasing, which is built on the knowledge about whole business objectives and stakeholders’ interest, the knowledge about the suppliers and their capabilities and potential, the knowledge about the people and their emotion towards relationship and culture; and the knowledge about technology up-taking.