Information Processing

- Details

- Category: Accounting

- Hits: 21,334

Accounts, Debits, and Credits

The previous chapter showed how transactions caused financial statement amounts to change. “Before” and “after” examples, etc. was used to develop the illustrations. Imagine if a real business tried to keep up with its affairs this way! Perhaps a giant chalk board could be set up in the accounting department.

As transactions occurred, they would be called in to the department and the chalk board would be updated. Chaos would quickly rule. Even if the business could manage to figure out what its financial statements were supposed to contain, it probably could not systematically describe the transactions that produced those results. Obviously, a system is needed.

It is imperative that a business develop a reliable accounting system to capture and summarize its voluminous transaction data. The system must be sufficient to fuel the preparation of the financial statements, and be capable of maintaining retrievable documentation for each and every transaction

In other words, some transaction logging process must be in place. In general terms, an accounting system is a system where transactions and events are reliably processed and summarized into useful financial statements and reports. Whether this system is manual or automated, the heart of the system will contain the basic processing tools: accounts, debits and credits, journals, and the general ledger. This chapter will provide insight into these tools and the general structure of a typical accounting system.

Accounts

The records that are kept for the individual asset, liability, equity, revenue, expense, and dividend components are known as accounts. In other words, a business would maintain an account for cash, another account for inventory, and so forth for every other financial statement element. All accounts, collectively, are said to comprise a firm’s general ledger. In a manual processing system, you could imagine the general ledger as nothing more than a notebook, with a separate page for every account.

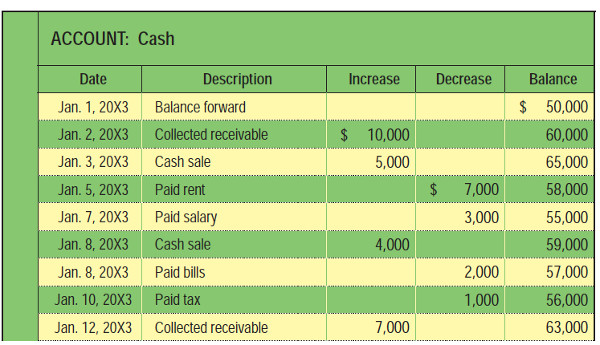

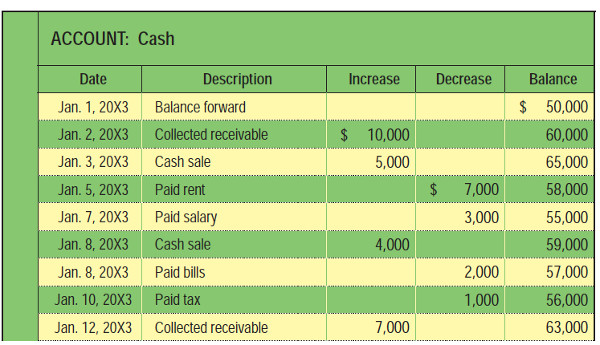

Thus, you could thumb through the notebook to see the “ins” and “outs” of every account, as well as existing balances. An account could be as simple as the following:

This account reveals that cash has a balance of $63,000 as of January 12. By examining the account, you can see the various transactions that caused increases and decreases to the $50,000 beginning of month cash balance. In many respects, this Cash account resembles the “register” you might keep for a wallet style check book. If you were to prepare a balance sheet on January 12, you would include cash for the indicated amount (and, so forth for each of the other accounts comprising the entire financial statements).

Debits and Credits

Without a doubt, you have heard or seen a reference to debits and credits; perhaps you have had someone “credit” your account or maybe you have used a “debit” card to buy something. Debits (abbreviated “dr”) and credits (abbreviated “cr”) are unique accounting tools to describe the change in a particular account that is necessitated by a transaction. In other words, instead of saying that cash is “increased” or “decreased,” we say that cash is “debited” or “credited.”

This method is again traced to Pacioli, the Franciscan monk who is given credit for the development of our enduring accounting model. Why add this complexity -- why not just use plus and minus like in the previous chapter? You will soon discover that there is an ingenious answer to this question!

Understanding the answer to this question begins by taking note of two very important observations:

- every transaction can be described in debit/credit form and

- for every transaction, debits = credits

The Fallacy of ”+/-“ Nomenclature

The second observation above would not be true for an increase/decrease system. For example, if services are provided to customers for cash, both cash and revenues would increase (a “+/+” outcome). On the other hand, paying an account payable causes a decrease in cash and a decrease in accounts payable (a “-/-” outcome). Finally, some transactions are a mixture of increase/decrease effects; using cash to buy land causes cash to decrease and land to increase (a “-/+” outcome). In the previous chapter, the “+/-” nomenclature was used for the various illustrations.

As you can tell by reviewing the illustration in Part 1, the “+/-” system lacks internal consistency. Therefore, it is easy to get something wrong and be completely unaware that something has gone amiss. On the other hand, the debit/credit system has internal consistency. If one attempts to describe the effects of a transaction in debit/credit form, it will be readily apparent that something is wrong when debits do not equal credits. Even modern computerized systems will challenge or preclude any attempt to enter an “unbalanced” transaction that does not satisfy the condition of debits = credits.

The Debit/Credit Rules

At first, it is natural for the debit/credit rules to seem confusing. However, the debit/credit rules are inherently logical (the logic is discussed at linked material in the online version of the text). But, memorization usually precedes comprehension. So, you are well advised to memorize the “debit/ credit” rules now. If you will thoroughly memorize these rules first, your life will be much easier as you press forward with your studies of accounting.

Assets/Expanses Dividends

As shown at right, these three types of accounts follow the same set of debit/credit rules. Debits increase these accounts and credits decrease these accounts. These accounts normally carry a debit balance. To aid your recall, you might rely on this slightly off–color mnemonic: D-E-A-D = debits increase expenses, assets, and dividends.

Liabilities/Revenues/Equity

These three types of accounts follow rules that are the opposite of those just described. Credits increase liabilities, revenues, and equity, while debits result in decreases. These accounts normally carry a credit balance.

Analysis of Transactions and Events

You now know that transactions and events can be expressed in “debit/credit” terminology. In

essence, accountants have their own unique shorthand to portray the financial statement consequence for every recordable event. This means that as transactions occur, it is necessary to perform an analysis to determine (a) what accounts are impacted and (b) how they are impacted (increased or decreased). Then, debits and credits are applied to the accounts, utilizing the rules set forth in the preceding paragraphs.

Usually, a recordable transaction will be evidenced by some “source document” that supports the underlying transaction. A cash disbursement will be supported by the issuance of a check. A sale might be supported by an invoice issued to a customer. Receipts may be retained to show the reason for a particular expenditure. A time report may support payroll costs. A tax statement may document the amount paid for taxes. A cash register tape may show cash sales. A bank deposit slip may show

collections of customer receivables. Suffice it to say, there are many potential source documents, and this is just a small sample. Source documents usually serve as the trigger for initiating the recording of a transaction.

The source documents are analyzed to determine the nature of a transaction and what accounts are impacted. Source documents should be retained (perhaps in electronic form) as an important part of the records supporting the various debits and credits that are entered into the accounting records. A properly designed accounting system will have controls to make sure that all transactions are fully captured. It would not do for transactions to slip through the cracks and go unrecorded.

There are many such safeguards that can be put in place, including use of renumbered documents and regular reconciliations. For example, you likely maintain a checkbook where you record your cash disbursements. Hopefully, you keep up with all of the checks (by check number) and perform a monthly reconciliation to make sure that your checkbook accounting system has correctly reflected all of your disbursements. A business must engage in similar activities to make sure that all transactions and events are recorded correctly. Good controls are essential to business success.

Determining an Account’s Balance

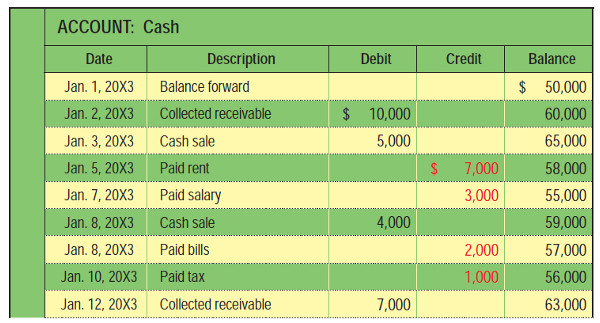

The balance of a specific account can be determined by considering its beginning (of period) balance, and then netting or offsetting all of the additional debits and credits to that account during the period. Earlier, an illustration for a Cash account was presented. That illustration was developed before you were introduced to debits and credits. Now, you know that accounts are more likely maintained by using the debit/credit system.

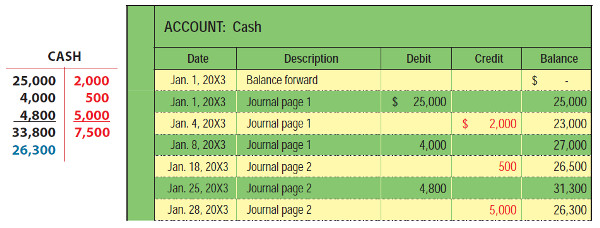

So, the Cash account is repeated below, except that the increase/decrease columns have been replaced with the more traditional debit/credit column leadings. A typical Cash account would look similar to this illustration:

A Common Misunderstanding About Credits

Many people wrongly assume that credits always reduce an account balance. However, a quick review of the debit/credit rules reveals that this is not true. Where does this notion come from? Probably because of the common phrase “we will credit your account.” This wording is often used when you return goods purchased on credit; but, carefully consider that your account (with the store) is on the store’s books as an asset account (specifically, an account receivable from you). Thus, the store is reducing its accounts receivable asset account (with a credit) when it agrees to “credit your account.”

On the other hand, some may assume that a credit always increases an account. This incorrect notion may originate with common banking terminology. Assume that Matthew made a deposit to his account at Monalo Bank. Monalo’s balance sheet would include an obligation (“liability”) to Matthew or the amount of money on deposit. This liability would be credited each time Matthew adds to his account. Thus, Matthew is told that his account is being “credited” when he makes a deposit.

The Journal

Most everyone is intimidated by new concepts and terminology (like debits, credits, journals, etc.).

But, learning can be made quite simple by relating new concepts to preexisting notions that are already well understood. So, think: what do you know about a journal (not an accounting journal, just any journal)? It’s just a log book, right? A place where you can record a history of transactions and events - usually in date (chronological) order. But, you knew that.

Likewise, an accounting journal is just a log book that contains a chronological listing of a company’s transactions and events. However, rather than including a detailed narrative description of a company’s transactions and events, the journal lists the items by a “form of shorthand notation.” Specifically, the notation indicates the accounts involved, and whether each is debited or credited. Remember what was said at the beginning of the chapter: “The system must be sufficient to fuel the preparation of the financial statements, and be capable of maintaining retrievable documentation for each and every transaction. In other words, some transaction logging process must be in place.”

The journal satisfies the need for this logging process! The general journal is sometimes called the book of original entry. This means that source documents are reviewed and interpreted as to the accounts involved. Then, they are documented in the journal via their debit/credit format. As such the general journal becomes a log book of the recordable transactions and events. The journal is not sufficient, by itself, to prepare financial statements. That objective is fulfilled by subsequent steps. But, maintaining the journal is the point of beginning toward that end objective.

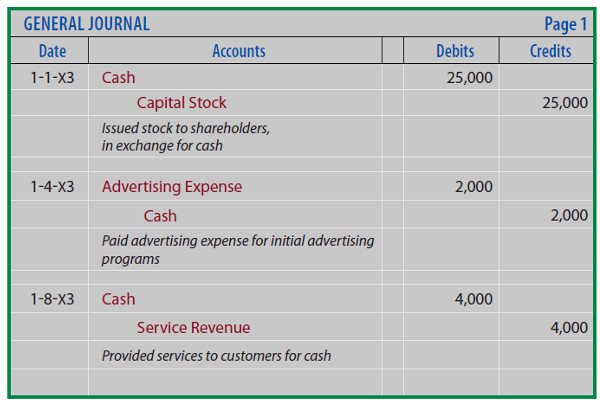

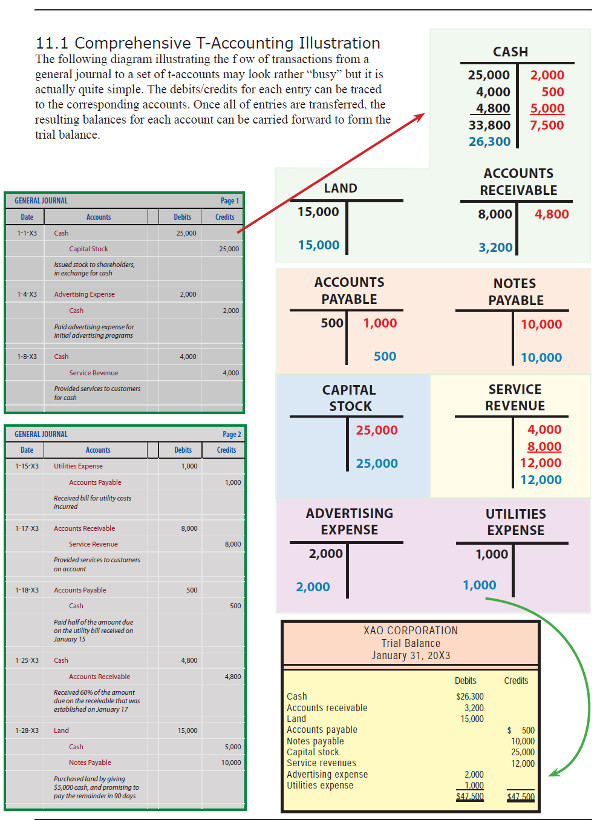

Illustrating the Accounting Journal

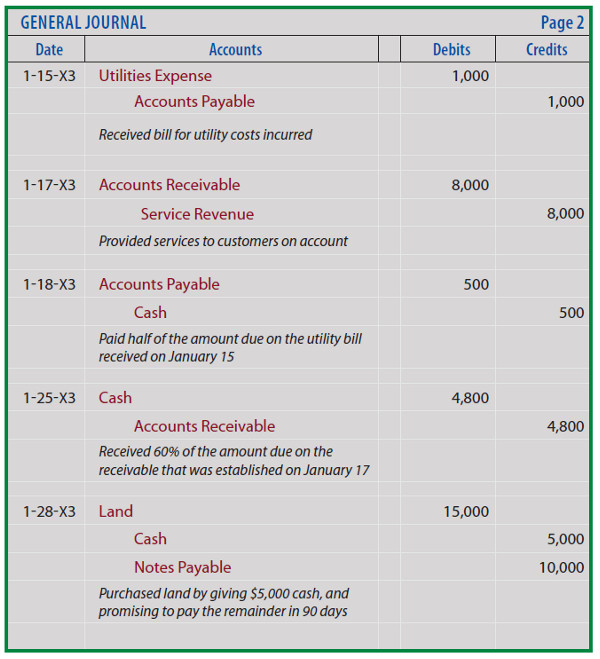

The following illustration draws upon the facts for the Xao Corporation. Specifically it shows the journalizing process for Xao’s transactions. You should review it carefully, specifically noting that it is in chronological order with each transaction of the business being reduced to the short-hand description of its debit/credit effects. You will also note that each transaction is followed by a brief narrative description; this is a good practice to provide further documentation. For each transaction, it is customary to list “debits” first (flush left), then the credits (indented right).

Finally, notice that a transaction may involve more than two accounts (as in the January 28 transaction below); the corresponding journal entry for these complex transactions is called a “compound” entry.

As you review the general journal for Xao, note that it is only two pages long. An actual journal for a business might consume hundreds and thousands of pages to document its many transactions. As a result, some businesses may maintain the journal in electronic form only.

Special Journals

First, the illustrated journal was referred to as a “general” journal. All transactions and events can be recorded in the general journal. However, a business may sometimes use “special journals.” Special journals are totally optional; they are typically employed when there are many redundant transactions.

Thus, a company could have special journals for each of the following: cash receipts, cash payments, sales, purchases, and/or payroll. These special journals do not replace the general journal. Instead,

Now that you have reviewed the journal entries for January, consider a few more points. they just strip out recurring type transactions and place them in their own separate journal. The transaction descriptions associated with each transaction found in the general journal are not normally needed in a special journal, given that each transaction is redundant in nature. Without special journals, you can well imagine how voluminous a general journal could become. But, for learning purposes, let’s just rely on the general journal to accomplish our goals.

Page Numbering

Second, notice that the illustrated journal consisted of two pages (labeled page 1 and page 2). Although the journal is chronological, it is helpful to have the page number indexing for transaction cross referencing and working backward from financial statement amounts to individual transactions.

But, What are the Account Balances?

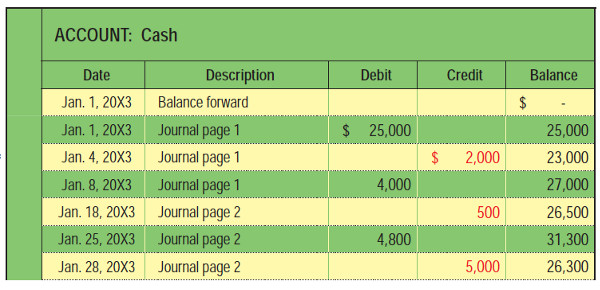

The general journal is a great tool to capture transaction and event details, but it certainly does nothing to tell a company about the balance in each specific account. For instance, how much cash does Xao Corporation have at the end of January? One could go through the journal and net the debits and credits to Cash ($25,000 - $2,000 + $4,000 - $500 + $4,800 - $5,000 = $26,300). But, this is tedious and highly susceptible to error. It would become virtually impossible if the journal were hundreds of pages long. A better way is needed. This is where the general ledger comes into play.

The General Ledger

As you just saw, the general journal is, in essence, a notebook that contains page after page of detailed accounting transactions. In contrast, the general ledger is, in essence, another notebook that contains a page for each and every account in use by a company. The ledger account for Xao would include the Cash page as illustrated below:

Xao’s transactions utilized all of the following accounts :

- Cash

- Accounts Receivable

- Land

- Accounts Payable

- Notes Payable

- Capital Stock

- Service Revenue

- Advertising Expense

- Utilities Expense

Therefore, Xao Corporation’s general ledger will include a separate page for each of these nine

accounts.

Posting

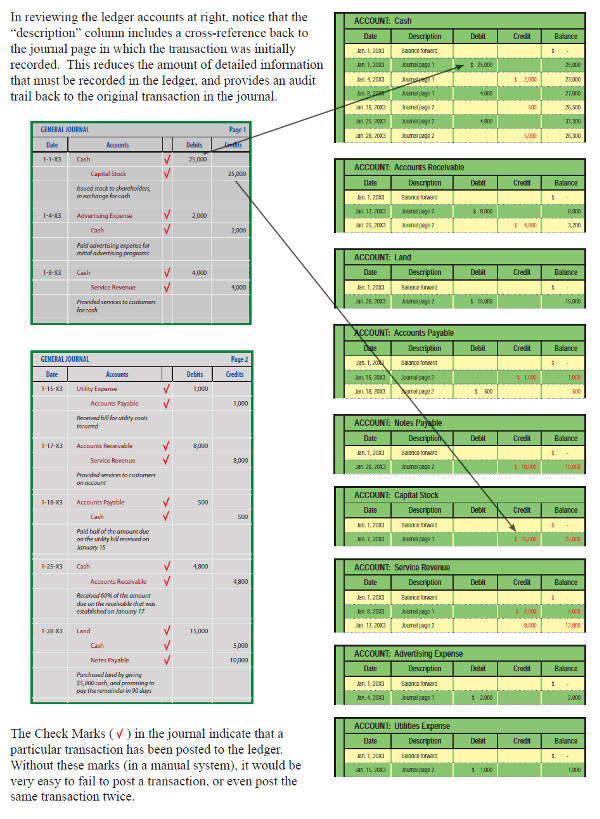

Before diving into the details of each account, let’s consider what we are about to do. We are going to determine the balance of each specific account by posting. To do this, we will copy (“post”) the entries listed in the journal into their respective ledger accounts.

In other words, the debits and credits in the journal will be accumulated (“transferred”/ “sorted”) into the appropriate debit and credit columns of each ledger page. Following is an illustration of the posting process. Notice that arrows are drawn to show how the first journal entry is posted. A similar process would occur for each of the other accounts.

In reviewing the ledger accounts at right, notice that the “description” column includes a cross-reference back to the journal page in which the transaction was initially recorded. This reduces the amount of detailed information that must be recorded in the ledger, and provides an audit trail back to the original transaction in the journal.

To Review

Thus far you should have grasped the following accounting “steps”:

- STEP 1: Each transaction is analyzed to determine the accounts involved

- STEP 2: A journal entry is entered into the general journal for each transaction

- STEP 3: Periodically, the journal entries are posted to the appropriate general ledger page

The Trial Balance

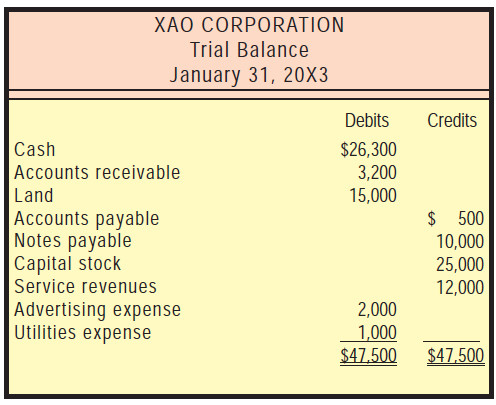

After all transactions have been posted from the journal to the ledger, it is a good practice to prepare a trial balance. A trial balance is simply a listing of the ledger accounts along with their respective debit or credit balances. The trial balance is not a formal financial statement, but rather a self-check to determine that debits equal credits. Following is the trial balance prepared from the general ledger of Xao Corporation.

Debits Equal Credits

Since each transaction was journalized in a way that insured that debits equaled credits, one would expect that this equality would be maintained throughout the ledger and trial balance. If the trial balance fails to balance, an error has occurred and must be located. It is much better to be careful as you go, rather than having to go back and locate an error after the fact. You should also be aware that a “balanced” trial balance is no guarantee of correctness. For example, failing to record a transaction, recording the same transaction twice, or posting an amount to the wrong account would produce a balanced (but incorrect) trial balance.

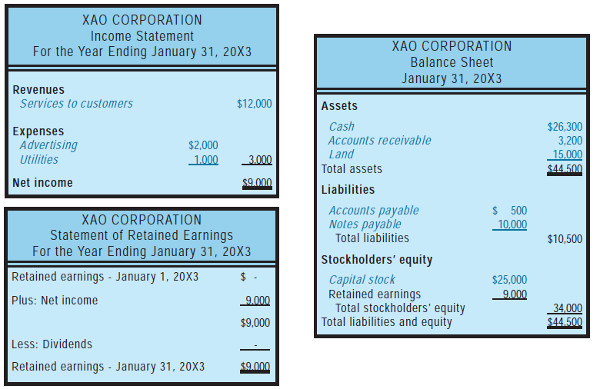

Financial Statements From the Trial Balance

In the next chapter you will learn about additional adjustments that may be needed to prepare a truly correct and up-to-date set of financial statements. But, for now, you can probably see that a tentative set of financial statements could be prepared based on the trial balance. The basic process is to transfer amounts from the general ledger to the trial balance, then into the financial statements:

In reviewing the following financial statements for Xao, notice that blue italics were used to draw attention to the items taken directly from the trial balance above. The other line items and amounts simply relate to totals and derived amounts within the statements. These statements would appear as follows:

Computerized Processing Systems

You probably noticed that much of the material in this chapter involves rather mundane processing.

Once the initial journal entry is prepared, the data are merely being manipulated to produce the ledger, trial balance, and financial statements. No wonder, then, that some of the first business applications that were computerized many years ago related to transaction processing. In short, the only “analytics” relate to the initial transaction recordation. All of the subsequent steps are merely mechanical, and are aptly suited to computerization. Many companies produce accounting software.

These packages range from the simple to the complex. Some basic products for a small business may be purchased for under $100. In large organizations, millions may be spent hiring consultants to install large enterprise-wide packages. Recently, some software companies have even offered accounting systems maintained on their own network, with the customers utilizing the internet to enter data and produce their reports.

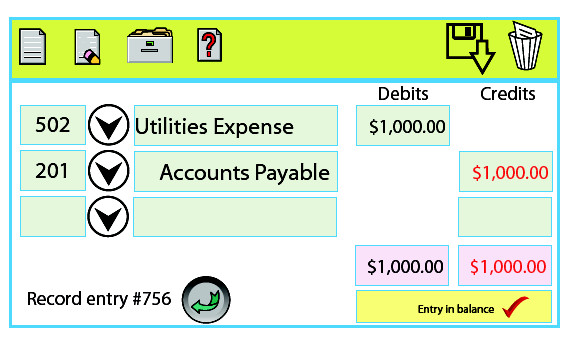

What do they Look Like

As you might expect, the look, feel, and function of software-based packages varies significantly. Each company’s product must be studied to understand its unique attributes. But, in general, accounting software packages:

- Attempt to simplify and automate data entry (e.g., a point-of-sale terminal may actually become a data entry device so that sales are automatically “booked” into the accounting system as they occur).

- Frequently divide the accounting process into modules related to functional areas such as sales/collection, purchasing/payment, and others.

- Attempt to be “user-friendly” by providing data entry blanks that are easily understood in relation to the underlying transactions.

- Attempt to minimize key-strokes by using “pick lists,” automatic call-up functions, and auto complete type technology.

- Are built on data-base logic, allowing transaction data to be sorted and processed based on any query structure (e.g., produce an income statement for July, provide a listing of sales to Customer Smith, etc.)

- Provide up-to-date data that may be accessed by key business decision makers.

- Are capable of producing numerous specialized reports in addition to the key financial statements.

Following is a very typical data entry screen. It should look quite familiar. After the data are input, The subsequent processing (posting, etc.) is totally automated. Despite each product’s own look and feel, the persons primarily responsible for the maintenance and operation of the accounting function must still understand accounting basics such as those introduced in this chapter: accounts, debits and credits, journal entries, etc.

Without that intrinsic knowledge, the data input decisions will quickly go astray, and the output of the computerized accounting system will become hopelessly trashed. So, while it is safe to assume that you will probably be working in a computerized accounting environment, it equally true to say that you should first come to understand the basic processing described in this and subsequent chapters. These principles will clearly guide you toward successful implementation and use of most any computerized accounting product, and the reports they produce.

T-accounts

A useful tool for demonstrating certain transactions and events is the “t-account.” Importantly, one would not use t-accounts for actually maintaining the accounts of a business. Instead, they are just a quick and simple way to figure out how a small number of transactions and events will impact a company. T-accounts would quickly become unwieldy in an enlarged business setting. In essence, taccounts are just a “scratch pad” for account analysis. They are useful communication devices to discuss, illustrate, and think about the impact of transactions. The physical shape of a t-account is a “T,” and debits are on the left and credits on the right.

The “balance” is the amount by which debits exceed credits (or vice versa). Below is the t-account for Cash for the transactions and events of Xao Corporation. Carefully compare this t-account to the actual running balance ledger account which is also shown (notice that the debits in black total to $33,800, the credits in red total to $7,500, and the excess of debits over credits is $26,300 -- which is the resulting account balance shown in blue).

Comprehensive T-Accounting Illustration

The following diagram illustrating the f ow of transactions from a general journal to a set of t-accounts may look rather “busy” but it is actually quite simple. The debits/credits for each entry can be traced to the corresponding accounts. Once all of entries are transferred, the resulting balances for each account can be carried forward to form the trial balance.

Chart of Account

A listing of all accounts in use by a particular company is called the chart of accounts. Indivi dual accounts are often given a specific reference number. The numbering scheme helps keep up with the accounts in use, and helps in the classification of accounts. For example, all assets may begin with ‘‘1’’ (e.g., 101 for Cash, 102 for Accounts Receivable, etc.), liabilities with “2,” and so forth. A simple chart of accounts for Xao Corporation might appear as follows:

- No. 101: Cash

- No. 102: Accounts Receivable

- No. 103: Land

- No. 201: Accounts Payable

- No. 202: Notes Payable

- No. 301: Capital Stock

- No. 401: Service Revenue

- No. 501: Advertising Expense

- No. 502: Utilities Expense

The assignment of a numerical account number to each account assists in data management, in much

Control and Subsidiary Accounts

Some general ledger accounts are made of many sub-components. For instance, a company may have total accounts receivable of $19,000, consisting of amounts due from Compton, Fisher, and Moore. The accounting system must be sufficient to reveal the total receivables, as well as amounts due from each customer. Therefore, sub-accounts are used. For instance, in addition to the regular general ledger account, separate auxiliary receivable accounts would be maintained for each customer, as shown in the following illustration:

The total receivables are the sum of all the individual receivable amounts. Thus, the Accounts Receivable general ledger account total is said to be the “control account” or control ledger, as it represents the total of all individual “subsidiary account” balances. The company’s chart of accounts will likely be based upon some convention such that each subsidiary account is a sequence number within the broader chart of accounts.

For instance, if Accounts Receivable bears the account number 102, you would expect to find that individual customers might be numbered as 102.001, 102.002, 102.003, etc. It is simply imperative that a company be able to reconcile subsidiary accounts to the broader control account that is found in the general ledger. Here, computers can be particularly helpful in maintaining the detailed and aggregated data in perfect harmony.