Economic equilibrium a system of free markets is stable

- Details

- Category: Economics

- Hits: 6,041

Economists have long been drawn to the idea that the economy might follow predictable mathematical laws, much like Newton’s laws of motion. Just as Newton reduced the complexities of the physical world to three fundamental equations, could similar relationships be found in the ever-changing world of markets?

One of the many reasons that people save is to send their children to college. Another is to make a down payment on a home. Yet another is for those years after people stop working. There are different methods of saving for retirement, each having different risks. As you read this section, you’ll learn about special savings plans and the amount of risk involved in these investments.

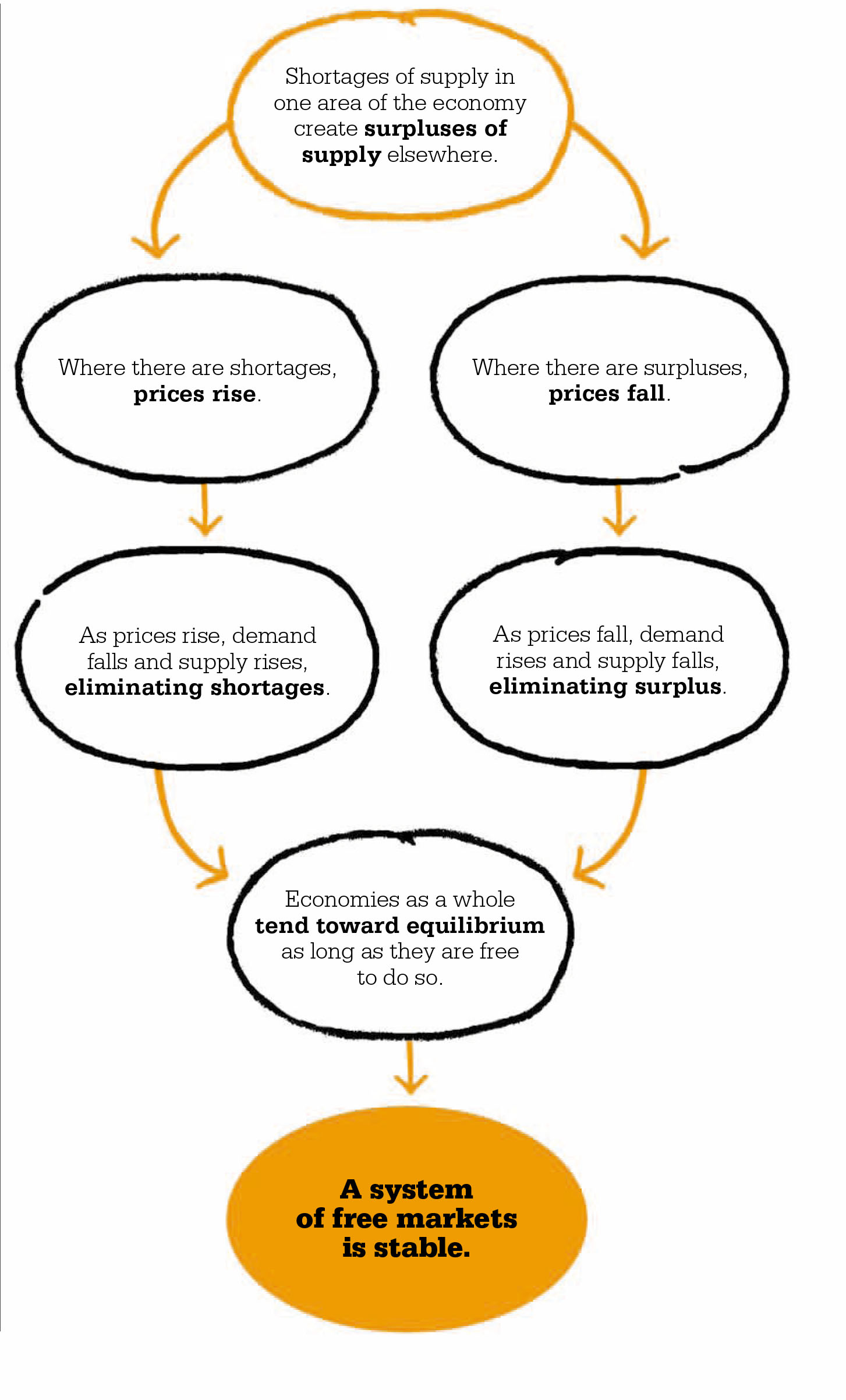

Economic equilibrium, particularly in the context of general equilibrium theory, suggests that a system of free markets can be stable under certain conditions. Here’s why:

Market Forces Push Toward Equilibrium

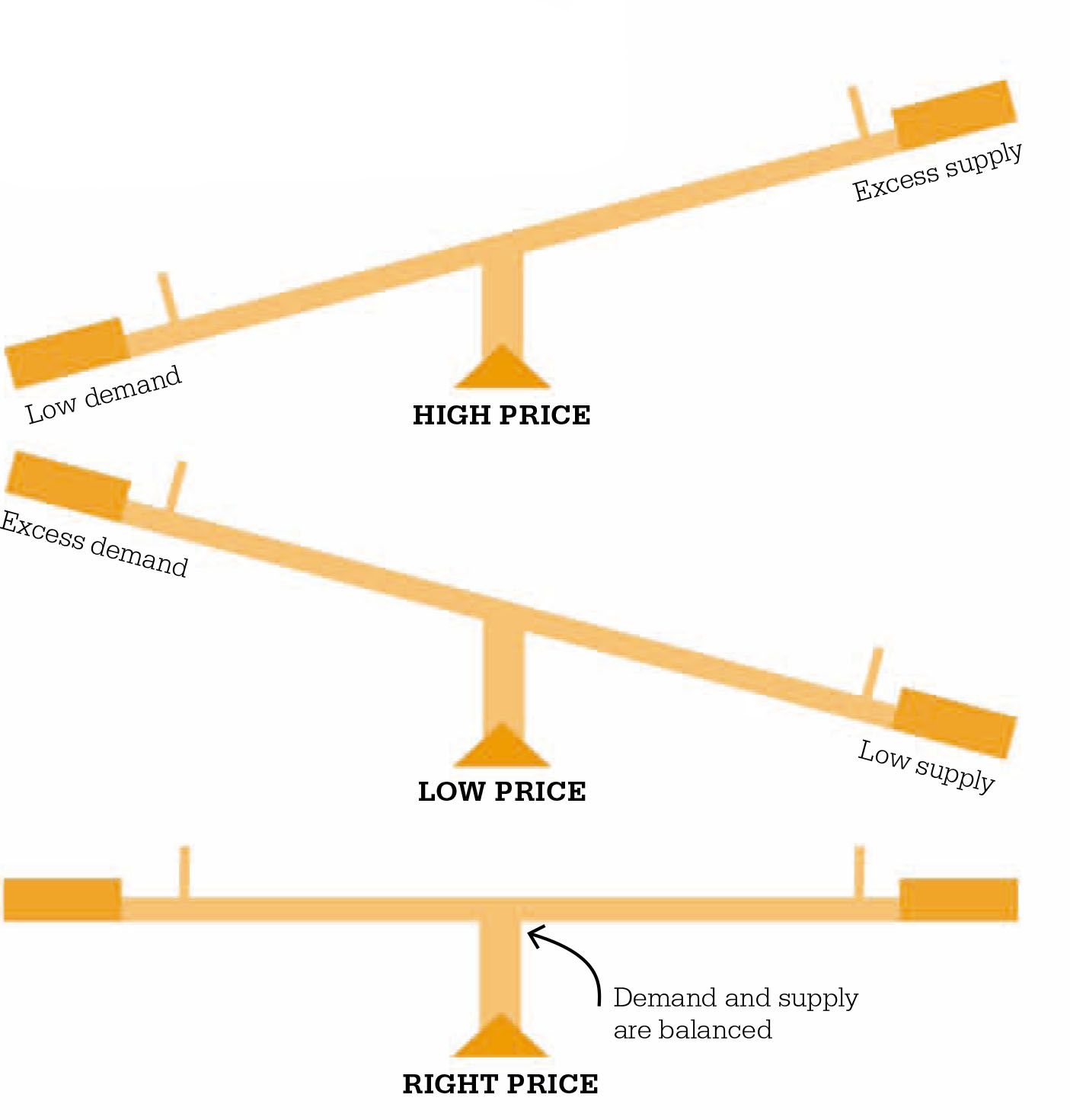

In a free market, supply and demand naturally adjust prices. If there’s excess supply (a surplus), prices fall, encouraging more consumption and less production until balance is restored. If demand exceeds supply (a shortage), prices rise, reducing demand and increasing production. This self-regulating mechanism helps stabilize markets.

Walras' Law and the Adjustment Process

Léon Walras proposed that if all but one market is in equilibrium, the remaining market must also be in equilibrium. This is because people only spend what they earn—if money is flowing smoothly through most sectors, imbalances in the last sector tend to resolve automatically.

The Role of Competition

In a free market with many buyers and sellers, competition ensures that resources are allocated efficiently. If one company sets prices too high, competitors will undercut them. If wages are too low, workers will move to better-paying jobs. These adjustments keep the system stable over time.

Assumptions of Stability

For equilibrium to hold, several conditions must be met:

- Rational behavior: Consumers and producers act logically to maximize utility and profit.

- Perfect information: Everyone knows prices and availability of goods.

- Flexible prices: Prices can rise or fall without restriction.

- Many participants: No single buyer or seller can control the market.

Is Stability Guaranteed?

Not always! Real-world markets face shocks—financial crises, government policies, or technological changes—that disrupt equilibrium. Some markets, like stock markets, experience bubbles and crashes rather than stable adjustments.

In summary, while free markets tend to move toward equilibrium due to natural price adjustments and competition, stability isn’t guaranteed in all cases, especially when external shocks or market failures occur.

Supply and demand

Walras began by focusing on how exchanges worked—how the prices of goods, the quantity of goods, and the demand for goods interact. In other words he was trying to pin down just how supply and demand tally. He believed that the value of something for sale depends essentially on its rareté—which means rarity, but was used by Walras to express just how intensely something is needed. I

n this respect Walras differed from many of his contemporaries, including Edgeworth and William Stanley Jevons, who believed that utility—either as pleasure or usefulness—is the key to value. Walras began to construct mathematical models to describe the relationship between supply and demand. These revealed that as price escalates, demand falls and supply climbs. Where demand and supply match, the market is in a state of equilibrium, or balance. This reflected the same kind of simple balancing forces that were evident in Newton’s laws of motion.

General equilibrium

To illustrate this equilibrium, imagine that today the current market price of mobile phones is $20. In a local market store owners have 100 phones for which they want $20. If 100 buyers visit the market, each willing to pay $20, the market for cheap mobiles is in equilibrium because the supply and demand are perfectly balanced with no shortages or surpluses see more about the law of supply.

Walras went on to apply the idea of equilibrium to the whole economy in order to create a theory of general equilibrium. This was based on the assumption that when goods are in surplus in one area, the price must be too high. Prices are judged too high by comparison, so if one market’s prices are too high, there must be another where prices are too low, causing a surplus in the higherpriced market.

Walras created a mathematical model for the whole economy, including goods such as chairs and wheat and factors of production such as capital and labor. Everything was interlinked and dependent on everything else. He insisted that interdependency is key; price changes do not take place in a vacuum—they only occur because of a change in supply or demand.

Moreover, when prices change, everything else also changes. One small change in one part of the economy can ripple through the entire economy. For example, suppose that a war breaks out in a major oil-producing country. Prices of oil across the world will rise, which will have far-reaching effects on governments, firms, and individuals—from increased prices at gas stations and increased heating costs at home, to being forced to cancel a now-expensive vacation or business trip.

The equilibrium… reestablishes itself automatically as soon as it is disturbed.

Léon Walras

Marie Esprit Léon Walras was born in Normandy, France, in 1834. As a young man he was captivated by bohemian Paris, but his father persuaded him that one of the romantic tasks of the future was to make economics a science. Walras was convinced—though he maintained his bohemian life until, destitute, he went to Lausanne as economics professor in 1870. It was there he developed his theory of general equilibrium. Walras believed that the organization of society was a matter of art outside the scientific realm of economics.

He had a strong sense of social justice and campaigned for land nationalization as a prelude to equal land distribution. In 1892, he retired to the town of Clarens overlooking Lake Geneva, where he fished and thought about economics until he died in 1910.

Key works :

- 1874 Elements of Pure Economics

- 1896 Studies in Social Economics

- 1898 Studies in Applied Economics

Toward equilibrium

Walras succeeded in reducing his mathematical model of an economy to a few equations containing prices and quantities. He drew two conclusions from his work. The first was that a state of general equilibrium is theoretically possible. The second was that wherever an economy started, a free market could move it toward general equilibrium. So a system of free markets could be inherently stable.

Walras showed how this might happen through an idea he called tâtonnement (groping), in which an economy gropes its way up to an equilibrium just as a climber gropes his way up a mountain. He thought about this by imagining a theoretical auctioneer to whom buyers and sellers submit information about how much they would buy or sell goods at different prices. The auctioneer then announces the prices at which supply equals demand in every market, and only then does buying and selling begin.

Flaws in the model

Walras was quick to point out that this was simply a mathematical model, designed to help economists. It was not intended to be taken to be a description of the real world. His work was largely ignored by his contemporaries, many of whom believed that real-world interactions are too complex and chaotic for a true state of equilibrium to develop. On a technical level Walras’s complex equations were too difficult for many economists to master, which was another reason why he was ignored, although his student Vilfredo Pareto later developed his work in new directions.

In the 1930s, two decades after Walras’s death, his equations came under the scrutiny of the brilliant Hungarian-born American mathematician, John von Neumann. Von Neumann exposed a flaw in Walras’s equations, showing that some of their solutions produced a negative price—which meant sellers would be paying buyers. John Maynard Keynes was particularly damning of Walras’s approach, arguing that general equilibrium theory is not a good picture of reality because economies are never in equilibrium. Keynes also argued that there is no use thinking about a long-term, and potentially agonizing, drive to equilibrium, because in the long-run, we are all dead.

However, Walras’s ideas have been rescued by the work of US economists Kenneth Arrow and Lionel W. McKenzie and French economist Gérard Debreu in the 1950s, who developed a sleeker model. Using rigorous mathematics, Arrow and Debreu derived conditions under which Walras’s general economic equilibrium would hold.

There was… a set of prices, one for each commodity, which would equate supply and demand for all commodities.

Computable economies Improvements to computers in the 1980s allowed economists to calculate the effects of interactions between multiple markets in actual economies. These computable general equilibrium (CGE) models applied Walras’s idea of interdependence to particular situations to analyze the impact of changing prices and government policies.

The attraction of CGE is that it can be used by large organizations—such as governments, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund—to make quick and powerful calculations showing the state of the whole economy as well as seeing the effects of changing different parameters.

Today, analysis of partial equilibrium—considering the forces that bring supply and demand into balance in a single market—is the first thing that an economics student learns. Walras’s insights about general equilibrium also continue to generate work at the cutting edge of economic theory. For most economists equilibrium and the existence of forces that return an economy to this state remain fundamental principles. These ideas are perhaps the essence of mainstream economic analysis.

Where prices are judged to be too high in one market, this will lead to an excess in supply in that market. Prices adjust to eliminate excesses in supply or demand across an economy in a process that Léon Walras called tâtonnement.