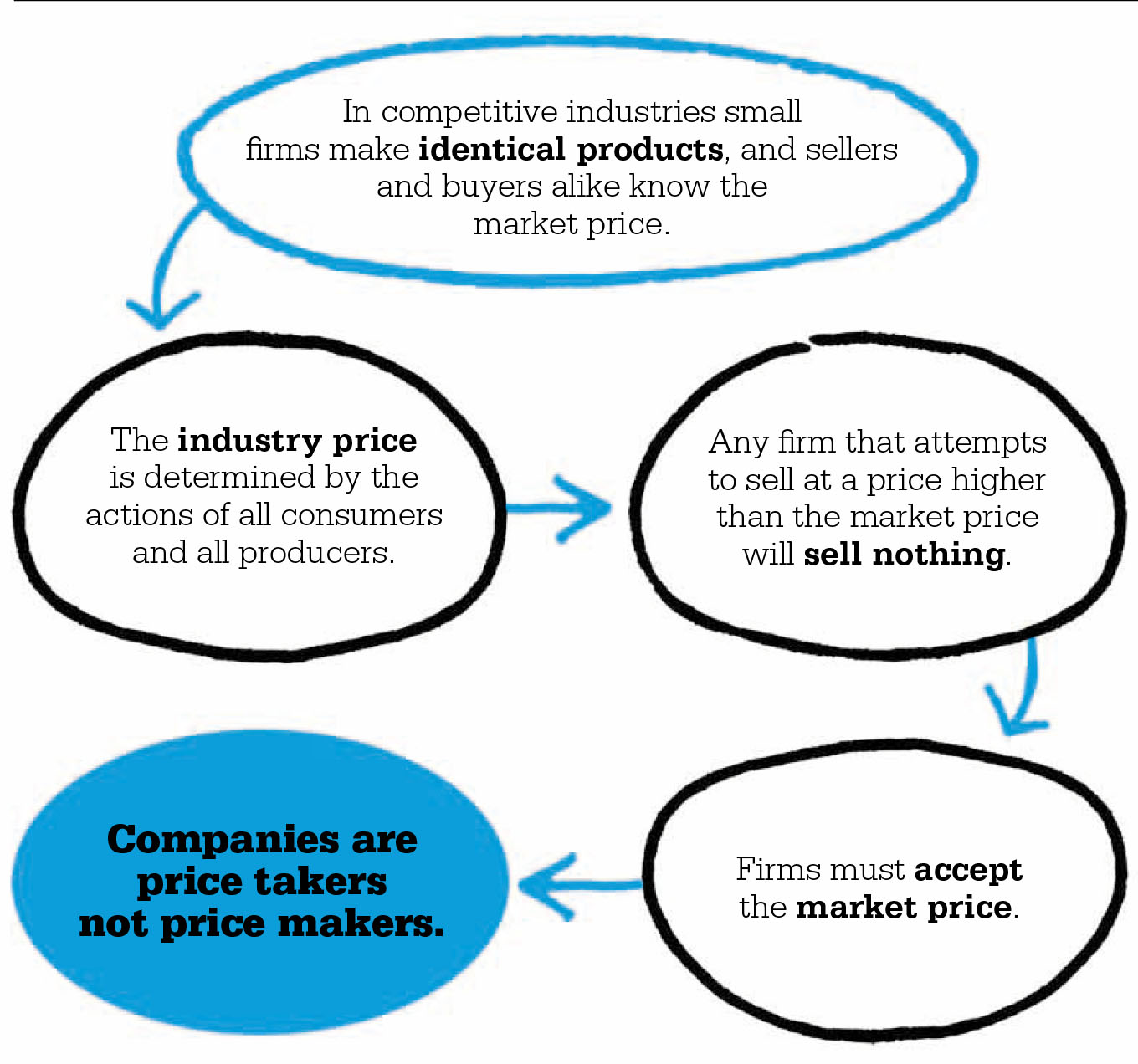

The competitive market: companies are price takers not price makers

- Details

- Category: Economics

- Hits: 8,843

In the dynamic world of economics, the competitive market stands as a fundamental concept that drives innovation, efficiency, and economic growth. Understanding the nuanced interactions between market players, their strategies, and the underlying economic principles is crucial for businesses, entrepreneurs, and economists alike. This comprehensive exploration delves into the multifaceted nature of competitive markets, examining everything from theoretical models to practical applications.

Perfect competition represents a foundational economic concept that provides insights into how markets theoretically operate under ideal conditions. Developed by British economist Alfred Marshall in his 1890 work "Economic Principles," this model offers a fascinating lens through which to understand market dynamics, pricing strategies, and economic interactions.

Perfect Competition: The Theoretical Ideal

Perfect competition represents an economic model that, while rarely achieved in pure form, serves as a critical benchmark for understanding market dynamics. In this idealized scenario, several key characteristics define the market structure:

Fundamental Characteristics of Perfect Competition

-

Numerous Market Participants: A perfect competition market features a large number of buyers and sellers, ensuring that no single entity can significantly influence market prices.

-

Homogeneous Products: All products in the market are identical, leaving little room for differentiation or brand-specific pricing strategies.

-

Perfect Information: Market participants have complete and instantaneous access to all relevant information, including pricing, product details, and market conditions.

-

Low Barriers to Entry and Exit: Businesses can freely enter or leave the market without substantial financial or regulatory obstacles.

-

Price Takers: Individual firms cannot set prices; they must accept the market-determined price as a given.

Competition in Action: Real-World Market Dynamics

While perfect competition remains a theoretical construct, real-world markets demonstrate more complex competitive interactions. Businesses must continuously adapt, innovate, and strategize to maintain their market position.

A perfect market is a district… in which there are many buyers and many sellers all so keenly on the alert and so well acquainted with one another’s affairs that the price of a commodity is always practically the same for the whole of the district.

Strategies for Competitive Engagement

- Differentiation: Creating unique value propositions that distinguish a product or service from competitors

- Cost Leadership: Developing efficient production processes to offer more competitive pricing

- Niche Market Targeting: Focusing on specialized segments with specific needs

- Continuous Innovation: Investing in research and development to stay ahead of market trends

Competitive Selling: Beyond Basic Transactions

Competitive selling transcends traditional sales approaches, requiring a sophisticated understanding of market dynamics, customer needs, and strategic positioning.

Key Elements of Competitive Selling

- Customer-Centric Approach: Understanding and anticipating customer requirements

- Value Communication: Effectively articulating unique product or service benefits

- Adaptive Pricing Strategies: Developing flexible pricing models responsive to market conditions

- Relationship Building: Establishing long-term connections that extend beyond individual transactions

Laborers will seek those employments, and capitalists those modes of investing their capital, in which… wages and profits are highest.

Short-Term Profits: Navigating Immediate Economic Challenges

In competitive markets, businesses often face the challenge of balancing immediate financial requirements with long-term strategic goals. Short-term profit strategies require careful consideration and nuanced approach.

Profit Optimization Techniques

- Operational Efficiency: Minimizing costs without compromising product quality

- Tactical Pricing: Implementing dynamic pricing strategies

- Resource Allocation: Strategic investment in high-potential market segments

- Risk Management: Developing robust contingency plans

The Impossibility of Perfection: Embracing Market Complexity

The concept of perfect competition highlights an essential economic truth: absolute perfection is unattainable. Markets are inherently dynamic, influenced by countless variables that defy simple mathematical models.

Factors Challenging Market Perfection

- Information Asymmetry: Unequal access to market information

- Regulatory Environments: Government policies and interventions

- Technological Disruptions: Rapid technological changes

- Human Behavior: Psychological factors influencing economic decisions

Alfred Marshall's Perspective: Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit

The renowned economist Alfred Marshall provided profound insights into the complex relationship between risk, uncertainty, and profit in competitive markets.

Marshall's Key Observations

- Risk as an Integral Component: Economic activities inherently involve risk and potential reward

- Uncertainty as a Driver of Innovation: Entrepreneurs navigate uncertain environments to create value

- Profit as Compensation: Financial returns reflect the risks and challenges undertaken by market participants

Marshall's Fundamental Principles

- Economic Equilibrium: Markets tend towards a balance between supply and demand

- Marginal Analysis: Understanding the incremental impact of economic decisions

- Human Capital Valuation: Recognizing the importance of skills, knowledge, and entrepreneurial capabilities

The Core Assumptions of Perfect Competition

Marshall's perfect competition model rests on three critical assumptions:

- Numerous Market Participants: The market consists of so many firms and customers that individual participants have negligible individual impact.

- Product Uniformity: All firms sell identical products, leaving consumers indifferent about their source.

- Market Accessibility: Firms can freely enter or exit the industry, with easy access to production resources.

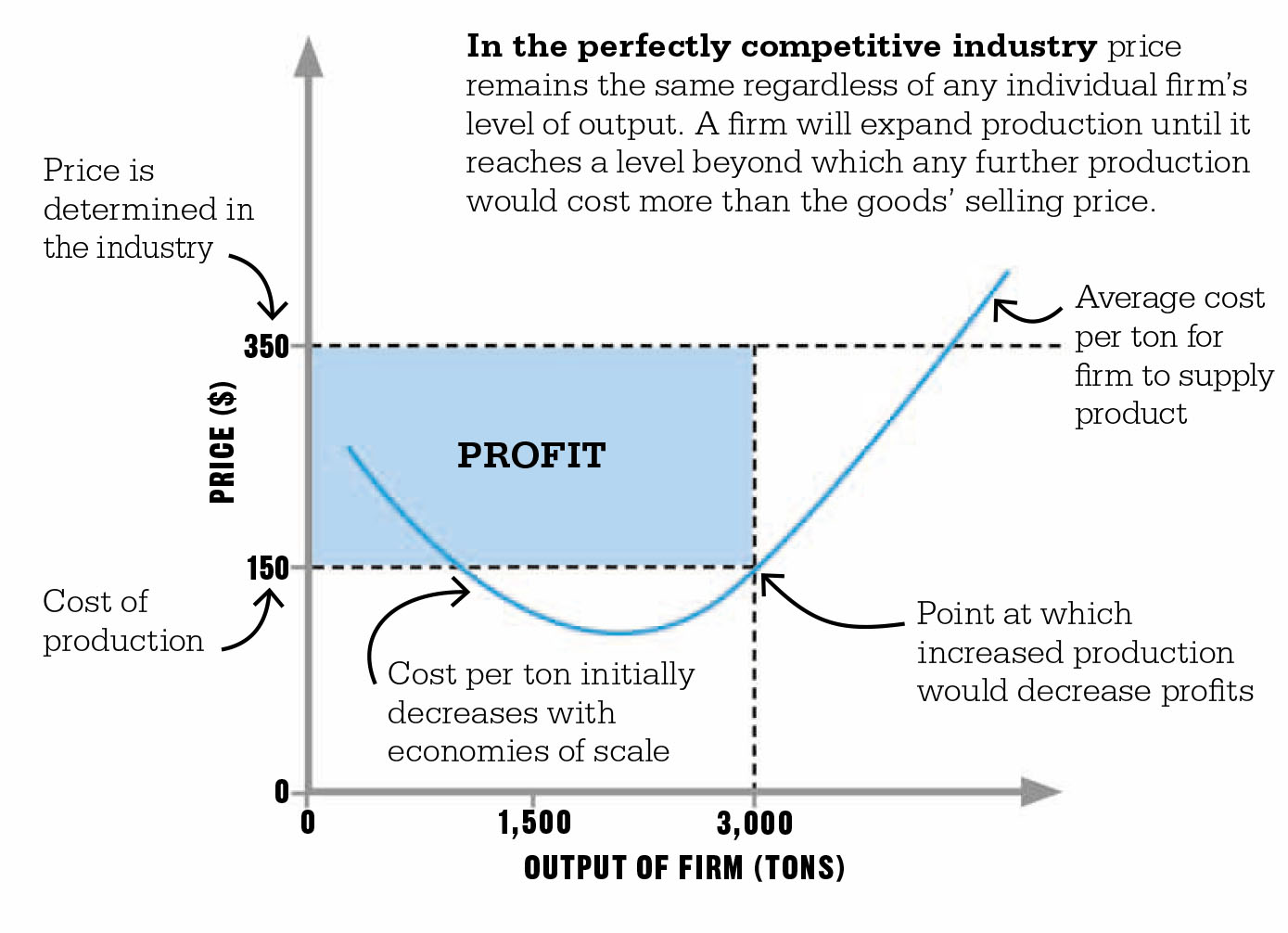

How Perfect Competition Works

In a perfectly competitive market, several key characteristics emerge:

Price Determination

Firms are price-takers, not price-makers. The market collectively determines the price, and individual firms must accept this price or cease operations. Any attempt to charge higher prices would result in zero sales due to perfect consumer information.

Profit Dynamics

While firms might initially enjoy high profits, market mechanics quickly normalize earnings:

- New entrants are attracted by initial high profits

- Increased supply drives prices down

- Profits eventually stabilize at a "normal" level

Real-World Example: Currency Markets

Foreign currency exchange provides a near-perfect illustration of this model. Multiple sellers, standardized products, and transparent pricing create conditions remarkably close to perfect competition.

Critiques of the Perfect Competition Model

Economists have raised significant challenges to Marshall's theory:

- Few real-world industries truly meet all model requirements

- The model suggests a passive market structure

- It fails to capture the dynamic nature of entrepreneurial competition

Alternative Perspectives

Economists like Friedrich Hayek argued that competition is a dynamic discovery process, not a static price-matching exercise. This perspective emphasizes innovation, adaptation, and constant market evolution.

Understanding Risk and Uncertainty

Frank Knight's groundbreaking work further refined the model by distinguishing between:

- Measurable Risk: Predictable uncertainties that can be insured or factored into costs

- Immeasurable Uncertainty: The unpredictable future that entrepreneurs navigate

Final Thoughts

While perfect competition might be more theoretical than practical, it remains a crucial framework for understanding market mechanisms. It provides economists and business strategists with a baseline model to analyze more complex market interactions.

Conclusion: Embracing Market Complexity

The competitive market represents a complex, ever-evolving ecosystem where businesses must continuously adapt, learn, and innovate. While theoretical models like perfect competition provide valuable insights, real-world markets demand flexibility, strategic thinking, and a deep understanding of economic principles.

Successful market participants recognize that competition is not merely about winning but about creating value, meeting customer needs, and contributing to broader economic development.

Understanding competitive markets requires a holistic approach that combines theoretical knowledge, practical experience, and a willingness to embrace complexity. By studying market dynamics, learning from economic principles, and remaining adaptable, businesses and individuals can navigate the challenging yet exciting world of economic interactions.