What Is Economics

- Details

- Category: Economics

- Hits: 15,722

Economics is a fascinating social science that explores how individuals, businesses, governments, and societies make critical decisions in a world of limited resources. At its core, economics seeks to understand the complex ways humans allocate, produce, distribute, and consume goods and services under conditions of scarcity. From analyzing individual choices to examining global market trends, economics provides a powerful lens for comprehending human behavior, resource management, and the intricate systems that drive our world's economic interactions.

This comprehensive exploration will delve into the fundamental principles that form the backbone of economic thinking. We'll unpack the basic economic problem of scarcity, examine the factors of production, investigate the concept of trade-offs, and introduce the production possibilities curve. By understanding these foundational concepts, readers will gain insight into how economists think, the models they use to explain economic phenomena, and the various schools of economic thought that have shaped our understanding of economic systems throughout history.

The BIG Idea

Scarcity is the basic economic problem that requires people to make choices about how to use limited resources.

Why It Matters ?

Have you ever wanted to buy something or to participate in an activity, but you couldn’t because you didn’t have enough income or time? How do scarce resources like time and income affect you and everyone around you? In this chapter, read to learn about what economics is and how it is part of your daily life.

The Basic Problem in Economics

ECONOMICS IS EVERYWHERE

Harry Potter may seem like he lives in a world where wizards have a wand and receive instant gratification, but that’s a view that needs to be demolished by the Womping Willow. Scarcity exists in the magic world just as much as in the Muggle world.

There are a limited number of tickets to the Quidditch World Cup, magical creatures only shed so many feathers or hairs to go into wands, and not everyone has an invisibility cloak. J.K. Rowling’s fictional world has its own central government (the Ministry of Magic), owl postal system, jail, hospital, news media, and public transport, not to mention Gringotts Bank and a special wizard currency. There are enough institutions to make Adam Smith salivate.

With scarcity and a monetary system, the Harry Potter series should be a case study for any economics course.

Starting at a very young age, many Americans use the words want and need interchangeably. How often do you think about what you “want”? How many times have you said that you “need” something? When you say, “I need some new clothes,” do you really need them, or do you just want them? As you read this section, you’ll find that economics deals with questions such as these.

Wants, Needs, and Choices

The basic problem in economics is how to satisfy unlimited wants with limited resources.

Economics & You

Think of the last time you said that you needed something. Was the object really necessary for your survival? Read on to learn that people must make choices about how to spend their limited resources.

What is economics? Economics is the study of how individuals, families, businesses, and societies use limited resources to fulfill their unlimited wants. Economics is divided into two parts. Microeconomics deals with behavior and decision making by small units such as individuals and firms.

Macroeconomics deals with the economy as a whole and decision making by large units such as governments.

People often confuse wants with needs. When they use the word need, they really mean that they want something they do not have. Obviously, everyone needs certain things, such as food, clothing, and shelter, to survive. To economists, however, anything other than what people need for basic survival is a want. People want such items as new cars and electronics, but they often convince themselves they need these things. In a world of limited resources, individuals satisfy their unlimited wants by making choices.

Like individuals, businesses must also make choices.

Businesspeople make decisions daily about what to produce now, what to produce later, and what to stop producing. Societies, too, face choices about how to utilize their resources. How these choices are made is the focus of economics.

- economics: the study of how people make choices about ways to use limited resources to fulfill their wants

- microeconomics: the branch of economic theory that deals with behavior and decision making by small units such as individuals and firms

- macroeconomics: the branch of economic theory dealing with the economy as a whole and decision making by large units such as governments

The Problem of Scarcity

Scarcity exists because people’s incomes and time are limited.

Economics & You

If you were very wealthy, would your resources be unlimited? Read on to learn why scarcity exists for everyone.

The need to make choices arises because everything that exists is limited, although some items (such as trees in a large forest) may appear to be in abundant supply. At any single moment, a fixed amount of resources is available. At the same time, people have competing uses for these resources. This situation results in scarcity—the basic problem of economics.

Scarcity means that people do not and cannot have enough income and time to satisfy their every want. What you buy as a student is limited by the amount of income you have. Even if everyone in the world were rich, however, scarcity would continue to exist, because even the richest person in the world does not have unlimited time

Do not confuse scarcity with shortages. Scarcity always exists because of competing alternative uses for resources, whereas shortages are temporary. Shortages often occur, for example, after hurricanes or floods destroy goods and property.

The Factors of Production

Scarce resources require choices about uses of the factors of production: land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship.

Economics & You

If you have a job, how does the work you do fit in with the bigger economic picture? Read on to learn that labor is one of the factors of production.

When economists talk about scarce resources, they are referring to the factors of production, or resources needed to produce goods and services. Traditionally, economists have classified these productive resources as land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship.

Land

As an economic term, land refers to natural resources that exist without human intervention. “Land” includes actual surface land and water, as well as fish, animals, trees, mineral deposits, and other “gifts of nature.”

Labor

The work people do is labor—which is often called a human resource. Labor includes any work people do to produce goods and services. Goods are tangible items that people can buy, such as medicine, clothing, or computers. Services are activities done for others for a fee. Doctors, hair stylists, and Web-page designers all sell their services.

Capital

Another factor of production is capital—the manufactured goods used to make other goods and produce other services. The machines, buildings, and tools used in making automobiles, for example, are capital goods. The newly assembled goods are not considered capital unless they, in turn, produce other goods and services, such as when an automobile is used as a taxicab.

When capital is combined with land and labor, the value of all three factors of production increases. Think about the following situation. If you combine an uncut diamond (land), a diamond cutter (labor), and a diamond-cutting machine (capital), you end up with a highly valued gem.

Capital also increases productivity—that is, greater quantities of goods and services are produced in better and faster ways. Consider how much faster an optical check-reading scanner—a capital good—can sort checks as compared to an individual worker reading each one.

Entrepreneurship

The fourth factor of production is entrepreneurship. This refers to the ability of individuals to start new businesses, introduce new products and processes, and improve management techniques. Entrepreneurship involves initiative and willingness to take risks in order to reap profits.

Entrepreneurs must also incur the costs of failed efforts. About 30 percent of new business enterprises fail. Of the 70 percent that do survive, only a few become wildly successful.

Technology

Some economists add technology to the list of factors of production. Technology includes any use of land, labor, and capital that produces goods and services more efficiently. For example, computerized word processing was a technological advance over the typewriter. Today, the word technology is commonly used to describe new products and new methods of producing goods and services.

Effect on Income and Wealth

How much of each of the factors of production an individual has determines his or her wealth. The more land and capital you have, the richer you will probably be. The greater your entrepreneurial skills, the more income you might earn. In other words, the distribution of factors of production affects a nation’s income distribution—what percentage of Americans are rich and what percentage are poor. The same holds true across nations as well. Nations with many natural resources at their disposal, for example, tend to be wealthier than nations with few natural resources.

- factors of production: resources of land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship used to produce goods and services

- land: natural resources and surface land and water

- labor: human effort directed toward producing goods and services

- goods: tangible objects that can satisfy people’s wants or needs

- services: actions that can satisfy people’s wants or needs

- capital: previously manufactured goods used to make other goods and services

- productivity: the amount of output (goods and services) that results from a given level of inputs (land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship)

- entrepreneurship: when individuals take risks to develop new products and start new businesses in order to make profits

- technology: the use of science to develop new products and new methods for producing and distributing goods and services

Trade-Offs

As you learned in Section 1, scarcity forces people to make choices about how they will use their resources. In this section, you’ll learn that the effects of these choices may be far-reaching and long-lasting. For example, one day you may choose to either go to work for a company or open your own business. Such a decision would affect many aspects of your life, including how much you earn and how you manage your time.

Trade-Offs

Economic decisions always involve trade-offs that have costs.

Economics & You

Think about the last time you spent an hour watching television. Were there other ways you could have spent your time? Read on to learn about economic one way means giving up other alternatives.

The economic choices people make involve exchanging one good or service for another. If you choose to buy an iPod, you are exchanging your income for the right to own the iPod. Exchanging one thing for another is called a trade-off. Individuals, families, businesses, and societies are forced to make trade-offs every time they use their resources in one wayand not another.

The Cost of Trade-Offs

The cost of a trade-off is what you give up in order to get or do something else. Time, for example, is a scarce resource—there are only so many hours in a day—so you must choose how to use it. When you decide to study economics for an hour, you are giving up any other activities you could have chosen to do during that time.

Trade-Offs

If you decide to go to college rather than work full-time right after high school, you are giving up the opportunity to start making money right away. You also may have to take on the burden of student loans. These are the trade-offs you make to gain a college education and increase your potential earning power later.

In other words, there is a cost involved in time spent studying this book. Economists call this an opportunity cost— the value of the next best alternative that had to be given up to do the action that was chosen. You may have many trade-offs when you study—exchanging instant messages with your friends, going to the mall, watching television, or practicing the guitar, for example. But whatever you consider the single next best alternative is the opportunity cost of your studying economics for one hour.

A good way to think about opportunity cost is to realize that when you make a trade-off (and you always make trade-offs), you lose something. What do you lose? You lose the ability to engage in your next highest valued alternative. In economics, therefore, opportunity cost is always an opportunity that is given up.

Considering Opportunity Costs

Being aware of tradeoffs and their resulting opportunity costs is vital in making economic decisions at all levels. Whether they are aware of it or not, individuals and families make trade-offs every day. Businesses must consider trade-offs and opportunity costs when they choose to invest funds or hire workers to produce one good rather than another.

Consider an example at the national level. Suppose Congress approves $220 billion to finance new highways. Congress could have voted instead for increased spending on medical research. The opportunity cost of building new highways, then, is less medical research.

Production Possibilities Curve

A production possibilities curve shows the maximum combinations of goods and services that can be produced with a given amount of resources.

Economics & You

Imagine that you are taking two classes— economics and math. You can spend 10 hours per week studying. How will you decide how many hours to study for each subject? Read on to learn how a production possibilities curve helps people make such decisions.

Obviously, many businesses produce more than one type of product. An automobile company, for example, may manufacture several makes of cars per plant in a given year. What this means is that the company produces combinations of goods, which results in an opportunity cost.

Economists use a model called the production possibilities curve to show the maximum combinations of goods and services that can be produced from a fixed amount of resourcesin a given period of time. This curve can help determine how much of each item to produce, thus revealing the trade-offs and opportunity costs involved in each decision.

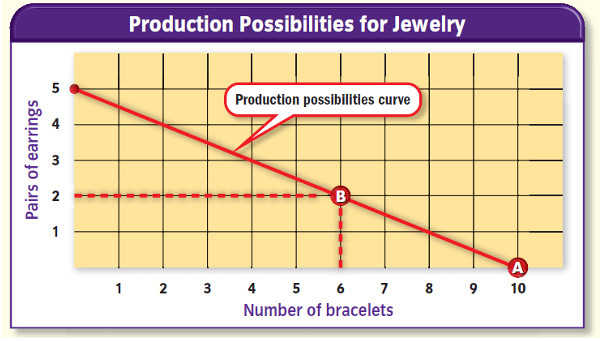

Imagine that you run a jewelry-making business. Working 20 hours a week, you have enough resources to make either 10 bracelets or 5 pairs of earrings. If you want to make some of both, Figure 1.3 below shows your production possibilities.

Figure 1.3 A Production Possibilities Curve

The curve here represents the production possibilities between bracelets and pairs of earrings during a 20-hour workweek. Note that if you make 10 bracelets (point A on the curve), you have no resources or time to make earrings. If you make only 6 bracelets (point B on the curve), you have enough resources and time to also make 2 pairs of earrings. Therefore, the opportunity cost of making 2 pairs of earrings is the 4 bracelets not made. Although you are making both bracelets and earrings, you— and businesses and nations— cannot produce more of one thing without giving up producing something else.

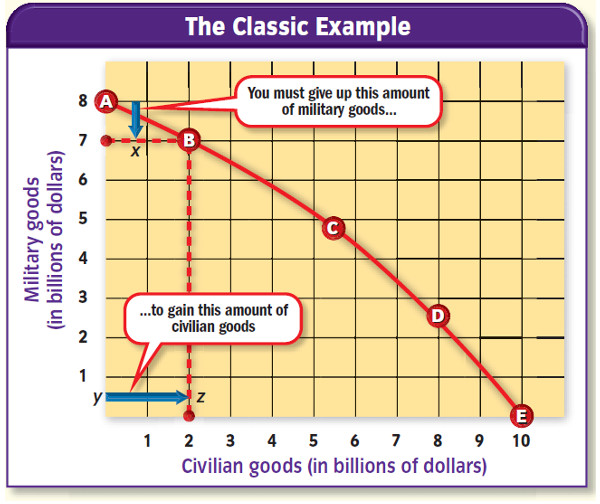

Figure 1.4 Production Possibilities—Guns vs. Butter

Nations produce combinations, or mixes, of goods. We often refer to the production of military goods as “guns” and the production of civiliangoods as “butter.” If a nation starts with all gun production and no butter production (point A), it can only get to some butter production (point B) by giving up some gun production. In other words, the cost of having some civilian goods (represented by the horizontal distance from point y to point z) is giving up some military goods (represented by the vertical distance from point A to point x).

The classic example for explaining production possibilities in economics is the trade-off between spending on military defense and civilian goods, sometimes referred to as guns versus butter. The extreme situation for any nation would be to use all of its resources to produce only military goods or only civilian goods. Of course, in reality, nations always produce some of both. Governments, like businesses, face production possibilities curves all of the time, so they know they have to give up production of one type of good or service in order to get more production of another.

Look at Figure 1.4 above. Point A on the graph represents a situation where all of a nation’s resources are being used to produce only military goods (guns). Point E represents the other extreme—a situation where all the nation’s resources are being used to produce only civilian goods (butter). The amount of military goods given up in a year is the opportunity cost for increasing the production of civilian goods, and vice versa.

In the United States, Congress and the president decide where on this curve the nation will be in terms of production of each type of good. The government collects revenue from citizens through taxes, and then it must decide how to use the revenue to best serve the nation. A production possibilities curve is useful in determining what the opportunity cost will be if a particular course of action is taken.

Of course, the real world doesn’t work exactly as our graphs predict. In the real world, it takes time to move from point A to point B on the curve. Also, in terms of nations, leaders must take factors other than economics into consideration when allocating resources; they also look at the political and social concerns of citizens. The important point to remember is that a production possibilities curve can help nations, businesses, and individuals decide how best to use their resources.

What Do Economists Do?

As you’ve learned, economics is concerned with the ways individuals and nations choose to use their scarce resources. Economists might analyze how the super-rich spend their income, for example, and the effect this spending has on the economy. As you read this section, however, you’ll find that something economists don’t do is judge whether there should be a social class of super-rich people.

Economic Models

Economists construct models to investigate the way that economic systems work.

Economics & You

Have you ever tried to predict the outcome of a sports match? On what information did you base your prediction? Read on to learn how economists use models to help them explain and predict economic behavior.

Remember that economics is concerned with the ways individuals, businesses, and nations choose to use their limited resources. To economists, the word economy means all the activity in a nation that together affects the production, distribution, and use of goods and services. When economists study specific parts of the economy—teenage employment rates or spending habits, for example—they often formulate theories and gather data from the real world. The theories that economists use in their work are called economic models. The study of these models can help explain and predict economic behavior.

You may be familiar with other types of models, such as model trains or airplanes, or models of buildings that architects have designed. Like these other types of models, economic models are simplified representations of the real world.

Economists test these economic models, and the solutions that result from these tests often become the basis for actual decisions by private businesses or government agencies. Keep in mind, though, that no economic model records every detail and relationship that exists about a problem to be studied. A model will show only the basic factors needed to analyze the problem.

- economy: the production and distribution of goods and services in a society

- economic model: a theory or simplified representation that helps explain and predict economic behavior in the real world

What Models Show

Physicists, chemists, biologists, and other scientists use models to understand in simple terms the complex workings of the world. One purpose of economic models is to show visual representations of consumer, business, or other economic behavior. Economic models all relate to the way individuals (as consumers) and businesspeople react to changes in the world around them. The most common economic model is a line graph explaining how consumers react to changes in the prices of goods and services. You’ll learn about this model in Chapter 7.

Economic models assume that some factors remain constant. In studying the production possibilities curve for making jewelry in Trade-Offs , for example, we assumed that the price of inputs (beads, wire, and so on) would not increase. We also assumed that inclement weather would not close schools for a day, which would have enabled you to work more than 20 hours a week on jewelry.

Why are these constant-factor assumptions important? Economists realize that, in the real world, several things may be changing at once. Using a model holds everything steady except the variables assumed to be related. In the same way that a map does not show every alley and building in a given location, economic models do not record every detail and relationship that exists about a problem to be studied. A model will show only the basic factors needed to analyze the problem at hand.

Creating a Model

Models are useful if they help us analyze the way the real world works. An economist begins with some idea about the way things work, then collects facts and discards those that are not relevant. Let’s assume that an economist wants to find out why teenage unemployment rises periodically. Perhaps this unemployment occurs when the federal minimum wage goes up, thereby forcing employers to pay their teenage workers more or to lay some workers off. The economist can test this theory, or model, in the same way that other scientists test a hypothesis—an educated guess or prediction.

Testing a Model

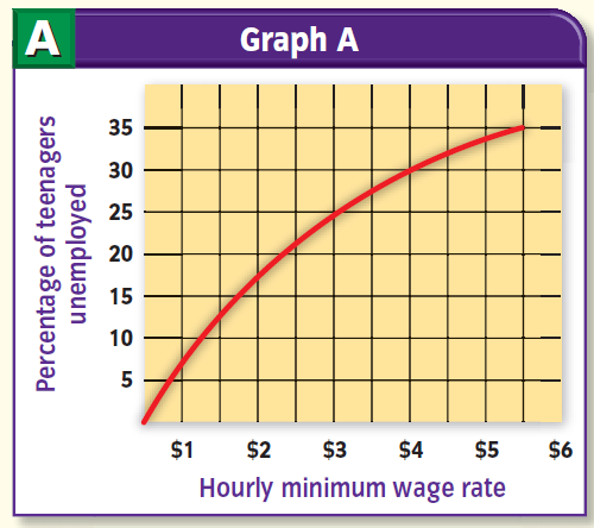

Testing a model, or hypothesis, allows economists to see if the model does a good job of representing reality. Suppose an economist has developed the model shown in Graph A of Figure 1.5 on the next page. The economist would collect data on the amount of teenage unemployment every year for the last 30 years. He or she would also gather 30 years of information on federal legislation that increased the legal minimum wage paid to teenagers.

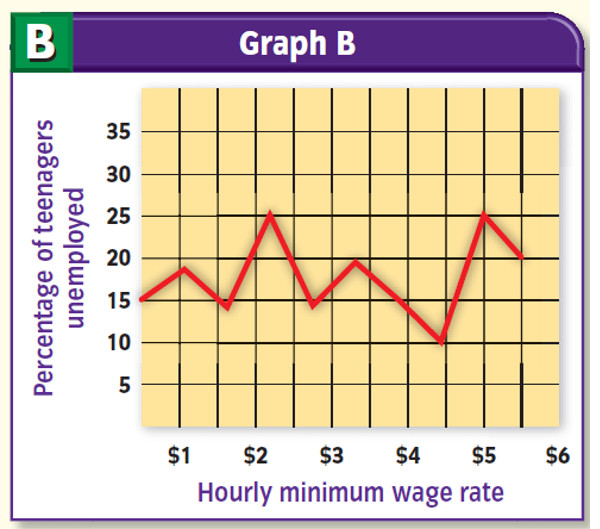

Figure 1.5 Economic Models

Graph A This graph supports the theory that a direct relationship exists between increases in the minimum wage rate and increases in teenage unemployment.

Graph B This graph does not support the theory that a direct relationship exists between the two factors studied.

The purpose of economic models is to show visual representations of consumer, business, or other economic behavior. Economic models, however, must be tested to see if they are useful.

The economist can be fairly satisfied with the model if teenage unemployment rose every time the minimum wage rate increased. But suppose that the data instead resulted in Graph B of Figure 1.5. In that case, the economist would have to develop another model to explain changes in teenage unemployment.

Applying Models to Real Life

Much of the work of economists involves attempts at predicting how people will react in a particular situation. Consider, for example, that some economists believe that to stimulate the economy, taxes should be cut and government spending increased. Cutting taxes, these economists believe, will put more income into consumers’ pockets, which will increase both spending and production.

People’s fears concerning higher taxes in the future, though, might cause them to save the extra income rather than spend it. As this example illustrates, some models take into account several factors that may influence people’s behavior.

Schools of Economic Thought

Competing economic theories are supported by economists from different schools of thought.

Economics & You

Have you and a friend ever read the same book or seen the same movie and then disagreed about what it was trying to say? Read on to learn about how economists disagree about economic theories.

Economists deal with facts. Their personal opinions and beliefs may nonetheless influence how they view those facts and fit them to theories. The government under which an economist lives also shapes how he or she views the world. As a result, not all economists will agree that a particular theory offers the best prediction. Often, economists from competing schools of thought claim that their theories are better than others’ theories in making predictions.

During a given period of time, a nation’s political leaders may agree with one school of economic thought and develop policies based on it. Later, other leaders may agree with another group of economists. Throughout American history, for example, many economists have stressed the importance of the government maintaining a “hands off” (or laissez-faire) policy in business and consumer affairs to prevent increased Stabilizing the National Economy. Other influential economists have proposed that the federal government should intervene in the economy to reduce unemployment and prevent inflation.

Learning about economics will help you predict what may happen if certain events occur or certain policies are followed. Economics will not tell you, however, whether the results will be good or bad. Judgments about results depend on a person’s values. Values are the beliefs or characteristics that a person or group considers important, such as religious freedom, equal opportunity, individual initiative, freedom from government meddling, and so on. Even having the same values, however, does not mean that people will agree about strategies, interpretation of data, or solutions to problems.

For example, those in favor of decreasing teenage unemployment in order to bring about economic opportunity may disagree about the best way to solve this problem. If you were a legislator, you might show your commitment to this value by introducing a bill to decrease teenage unemployment.

The economists who help you research the causes of teenage unemployment will tell you, based on their expertise, whether they think the proposed solution will actually reduce teenage unemployment.

Remember always that the science of economics is not used to judge whether a certain policy is good or bad. Economists only inform us as to likely outcomes of these policies.