Market Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning

- Details

- Category: Marketing

- Hits: 55,740

In this lesson, we will introduce you to the activities, viz., segmentation, targeting and positioning, that are collectively referred to as marketing strategy. After you work out this lesson, you should be able to:

- Segment the markets based on several segmentation variables

- Target a segment by identifying the fit between segment profitability and organizational capability

- Position your product/service so that it occupies a distinct and valued place in the target customers’ minds

In this lesson, we will discuss the following:

- The logic of segmentation

- Segmentation analysis

- Segmentation variables for consumer markets and industrial markets

- Targeting approaches

- Positioning identities

- Differentiation across the consumption chain

The development of a successful marketing strategy begins with an understanding of the market for the good or service. A market is composed of people or institutions with need, sufficient purchasing power and willingness to buy. The market place is heterogeneous with differing wants and varying purchase power.

The heterogeneous marketplace can be divided into many homogeneous customer segments along several segmentation variables. The division of the total market into smaller relatively homogeneous groups is called market segmentation.

Products seldom succeed by appealing to everybody. The reasons are simple: not every customer is profitable nor worth retaining, not every product appeals to every customer. Hence the organizations

look for a fit between their competencies and the segments’ profitability. The identified segments are then targeted with clear marketing communications.

Such communications are referred to as positioning the product or service in the mind of the customer so as to occupy a unique place. This involves identifying different points of differentiation and formulating a unique selling proposition (USP). In today’s marketplace, differentiation holds the key to marketing success. This lesson is about marketing strategy formulation which consists of market segmentation, targeting and positioning.

The logic of Segmentation

The concept of market segmentation has helped marketing decision making since the evolution of marketing. The goal of market segmentation is to partition the total market for a product or service into smaller groups of customer segments based on their characteristics, their potential as customers for the specific product or service in question and their differential reactions to marketing programs.

Because segmentation seeks to isolate significant differences among groups of individuals in the market, it can aid marketing decision making in at least four ways:

- Segmentation helps the marketer by identifying groups of customers to whom he could more effectively ‘target’ marketing efforts for the product or service

- Segmentation helps the marketer avoid ‘trial-and-error’ methods of strategy formulation by providing an understanding of these customers upon which he can tailor the strategy

- In helping the marketer to address and satisfy customer needs more effectively, segmentation aids in the implementation of the marketing concept

- On-going customer analysis and market segmentation provides important data on which long-range planning (for market growth or product development) can be based.

Although it is a very useful technique, segmentation is not appropriate in every marketing situation. If, for instance, a marketer has evidence that all customers within a market have similar needs to be fulfilled by the product or service in question (i.e. an undifferentiated market), one ‘mass’ marketing strategy would probably be appropriate for the entire market. However, in today’s market environment, it is unlikely that one would find either an entirely homogeneous market.

Criteria for Segmentation

If segmentation has to be useful in marketing decision making, then it must possess the following characteristics:

- Segments must be internally homogeneous - consumers within the segment will be more similar to each other in characteristics and behavior than they are to consumers in other segments.

- Segments must be identifiable - individuals can be ‘placed’ within or outside each segment based on a measurable and meaningful factor

- Segments must be accessible - can be reached by advertising media as well as distribution channels. Only then, the segments can be acted upon.

- Segments must have an effective demand - the segment consists of a large group of consumers and they have the necessary disposable income and ability to purchase the goods or services.

Segmentation Analysis

Here is a list of few general steps, referred to as segmentation analysis, that will be most often followed after the decision to employ market segmentation has been made. Examples of questions to be answered during each step are also given.

Step-1 Define the purpose and scope of the segmentation

- What are our Marketing Objectives?

- Are we looking for new segments or determining how to better satisfy existing ones?

- Will we use existing data or invest time and money in new research?

- What level of detail will be needed in the segmentation analysis?

Step-2 Analyze total Market Data

- What is the character of the total market? (e.g. size)

- Are there basic differences between users and non-users of the product class?

- Are there any factors that clearly distinguish users from non-users or users of different brands?

- What is our competitive position in the market now?

Step-3 Develop segment profiles

- What factor seems to differentiate groups of consumers most clearly?

- Are the profiles of each segment internally consistent?

Step-4 Evaluate segmentation

- What are the major similarities and differences among segments?

- Should the number of segments described be reduced or increased?

- How sensitive is this segmentation of the market to growth?

Step-5 Select target segment(s)

- Which segment(s) represents our best market opportunity?

- What further details do we know about the target segment’s characteristics and market behavior?

- If complete data on market behavior for the target segment are not available, can we make reasonable assumptions?

- Are we alone in competing for this target segment?

Step-6 Designing the marketing strategy for the target segment

- What type of product do these consumers want?

- What kinds of price, promotion or distribution tactics will best suit their needs?

- Would other segments react positively to a similar strategy? (if so, the segments should probably be merged)

Step-7 Reappraisal of segmentation

- Do we have the resources to carry out this strategy?

- If we wish to broaden or change our target definition in the future, how flexible is the strategy?

- If we wish to change some elements of the strategy in the future, how would that change probably influence the target segment?

- Does the target segment/strategic plan meet our objective? Does it fit our corporate strengths?

Segmenting the Consumer Markets

Consumer markets are those where the products are purchased by ultimate consumers for personal use. Industrial markets are those where the goods and services are purchased for use either directly or indirectly in the production of other goods and services for resale. Market segmentation of these markets uses different variables.

The consumer market segmentation variables appear to fall into two broad classes: consumers’ background characteristics and consumers’ market history. The following tables illustrate the most important factors and variables that have been found useful for market segmentation.

Table 1.6.1 Segmentation using consumer background characteristics

| Segmentation variable | Some examples of variables Measured | Comments |

| Geography |

|

Geographic segmentation is one of the oldest and most basic of market descriptors. In most cases, it alone is note sufficient for a meaningful consumer segmentation |

| Demographic |

|

Also basic and included as a variable in most segmentation analyses. Demographic profiles of segments are important especially when making later advertising media decisions |

| Psychographic |

|

Psychographic variables are more useful because there is often no direct link between demographic and market behavior variables. These consumer profiles are often tied more directly to purchase motivation and product usage |

| General life-style |

|

Provides a rich, multi-dimensional profile of consumers that integrates individual variables into a clearer pattern that describes the consumer’s routines and general ‘way of life’ |

Table 1.6.2 Segmentation using consumers’ market history

| Segmentation variable | Some examples of variables measured | Comments |

| Product usage |

|

Segmenting the market into heavy, medium, light and non-users gives a good understanding of the present situation in the market |

| Product benefit |

|

Very useful if the product can be positioned in a number of ways. The primary use of this variable segments the market into groups that look for different product benefits |

| Decision-process |

|

Use of this variable segments the market into price/non-price sensitive, shoppers/impulse buyers and other segments which characterize the market behavior of each group. Must be used in conjunction with analysis of consumer characteristics to allow identification of the individuals involved |

Segmenting the Industrial Markets

Industrial marketing needs to consider two important sets of characteristics of business buyers:

- the characteristics of the buyer as a consuming organization

- the behavioral characteristics of the buyer.

The first set includes such factors as the type of the organization, the size, the product requirements, the end use of the product, the organization capabilities and so on. The second set includes factors like the buying decision making process and considers the fact that it is in effect people and the organization, who take the decision.

These characteristics have led to a two-stage approach to industrial market segmentation starting with a macro segmentation and then going into a micro-segmentation. Between the macro and micro bases of industrial market

segmentation, there lie some useful bases of segmentation, as suggested by Shapiro and Bonoma in the Nested approach to segmenting the industrial markets. These intermediate bases of segmentation, viz., demographics, operating variables, purchasing approaches, situational factors and personal characteristics, are explained in Table 1.6.3.

The table lists major questions that business marketers should ask in determining which customers they want to serve. By targeting these segments instead of the whole market, companies have a much better chance to deliver value to customers and to receive maximum rewards for close attention to their needs.

Table 1.6.3 Major Segmentation variables for Industrial Markets

| Segmentationvariable | Examples of variables measured | Comments |

| Demographics |

|

|

| Operating variables |

|

|

| Purchasingapproaches |

|

|

| Situational factors |

|

|

| Personal characteristics |

|

|

Targeting Approaches

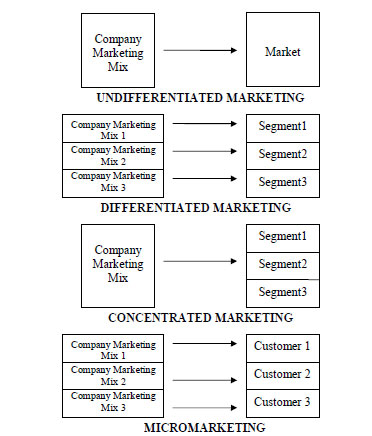

Target market selection is the next logical step following segmentation. Once the market-segment opportunities have been identified, the organization got to decide how many and which ones to target. Lot of marketing effort is dedicated to developing strategies that will best match the firm’s product offerings to the needs of particular target segments. The firm should look for a match between the value requirements of each segment and its distinctive capabilities. Marketers have identified four basic approaches to do this:

Undifferentiated Marketing

A firm may produce only one product or product line and offer it to all customers with a single marketing mix. Such a firm is said to practice undifferentiated marketing, also called mass marketing. It used to be much more common in the past than it is today. A common example is the case of Model T built by Henry Ford and sold for one price to everyone who wanted to buy. He agreed to paint his cars any color that consumers wanted, ‘as long as it is black’.

While undifferentiated marketing is efficient from a production viewpoint (offering the benefits of economies of scale), it also brings in inherent dangers. A firm that attempts to satisfy everyone in the market with one standard product may suffer if competitors offer specialized units to smaller segments of the total market and better satisfy individual segments.

Differentiated Marketing

Firms that promote numerous products with different marketing mixes designed to satisfy smaller segments are said to practice differentiated marketing.

It is still aimed at satisfying a large part of the total market. Instead of marketing one product with a single marketing program, the firm markets a number of products designed to appeal to individual parts of the total market.

By providing increased satisfaction for each of many target markets, a company can produce more sales by following a differentiated marketing approach. In general, it also raises production, inventory and promotional costs. Despite higher marketing costs, a company may be forced to practice differentiated marketing in order to remain competitive.

Concentrated Marketing

Rather than trying to market its products separately to several segments, a firm may opt for a concentrated marketing approach. With concentrated marketing (also known as niche marketing), a firm focuses its efforts on profitably satisfying only one market segment. It may be a small segment, but a profitable segment.

This approach can appeal to a small firm that lacks the financial resources of its competitors and to a company that offers highly specialized good and services. Along with its benefits, concentrated marketing has its dangers. Since this approach ties a firm’s growth to a particular segment, changes in the size of that segment or in customer buying patterns may result in severe financial problems. Sales may also drop if new competitors appeal successfully to the same segment. Niche marketing leaves the fortunes of a firm to depend on one small target segment.

Micro Marketing

This approach is still more narrowly focused than concentrated marketing. Micromarketing involves targeting potential customers at a very basic level, such as by the postal code, specific occupation or lifestyle. Ultimately, micromarketing may even target individuals themselves. It is referred to as marketing to segments of one. The internet allows marketers to boost the effectiveness of micromarketing.

With the ability to customize (individualization attempts by the firm) and to personalize (individualization attempts by the customer), the internet offers the benefit of mass customization – by reaching the mass market with individualized offers for the customers.

Figure 1.6.1 Market targeting approaches

Positioning

Having chosen an approach for reaching the firm’s target segment, marketers must then decide how best to position the product in the market. The concept of positioning seeks to place a product in a certain ‘position’ in the minds of the prospective buyers. Positioning is the act of designing the company’s offer so that it occupies a distinct and valued place in the target customers’ minds. In a world that is getting more and more homogenized, differentiation and positioning hold the key to marketing success!

The positioning gurus, Al Ries and Jack Trout define positioning as: Positioning is … your product as the customer thinks of it. Positioning is not what you do to your product, but what you do to the mind of your customer. Every product must have a positioning statement. A general form of such a statement is given below:

Product X is positioned as offering (benefit) to (target market) with the competitive advantage of (competitive advantage) based on (basis for competitive advantage) For example, the positioning statement of toothpaste X may read as follows:

Toothpaste X is positioned as offering to kids a toothpaste made especially for those kids who don’t like to brush with the competitive advantage of a mild fruit taste and lower foaming.

One way to think about positioning is to imagine a triangle, with the baseline anchored by the organization and competitor concerns and the apex, the customers. The marketer’s job is to find a positioning of the product or service that is both possible and compatible with organization constraints which uniquely places the product/service among competitive offerings so as to be most suitable to one or a number of segments of customers.

Positioning can be done along with different possibilities. Attribute positioning is when the positioning is based on some attribute of the product. Benefit positioning is when a derived benefit is highlighted as a unique selling proposition. Competitor positioning is when a comparison is drawn with the competitor and a differentiation from the competitor is emphasized. Product category positioning is when a product is positioned to belong to a particular category and not another category which probably is crowded.

Quality/price positioning is when the product is positioned as the best value for money. For example, a Pizza may be positioned on its taste or it’s natural contents or as an easy meal or with a thicker topping or as the lowest-priced offering the best value for money. Each one of them offers a distinct positioning possibility for a pizza.

In the positioning decision, caution must be taken to avoid certain positioning errors: Underpositioning is done when a unique, but not so important attribute is highlighted. As a result, the customer does not see any value in such a position.

Overpositioning is done when the product performance does not justify the tall claims of positioning. Confused positioning is when the customer fails to categorize the product correctly and the product ends up being perceived differently from what was intended.

Doubtful positioning is when the customer finds it difficult to believe the positioning claims.

The positioning map is a valuable tool to help marketers position products by graphically illustrating consumers’ perceptions of competing products within an industry.

For instance, a positioning map might present two different characteristics, price and quality, and show how consumers view a product and its major competitors based on these traits. Marketers can create a competitive positioning map from information solicited from consumers or from their accumulated knowledge about a market.

Positioning Identities

Positioning is creating an identity of your product. This identity is a cumulative of the following four positioning identities.

1. Who am I?

It refers to the corporate credentials like the origin, family tree and the ‘stable’ from which it comes from. For instance, think of the mental associations when a buyer buys a Japanese car and it is a Honda!

2. What am I?

It refers to functional capabilities. The perceived brand differentiation is formed using the brand’s capabilities and benefits. For instance, Japanese cars are known for their fuel-efficiency, reasonable-price and utility-value.

3. For whom am I?

It refers to the target segment for the brand. It identifies that market segment for which his brand seems to be just right and has a competitive advantage. For instance, the Japanese carmakers have traditionally focused on the quality conscious, value-seeking and a rather-serious car buyer

4. Why me?

It highlights the differential advantage of the brand when compared to the competing brands. It gives reasons as to why the customer should select this brand in preference to any other brand. For instance, Japanese carmakers have tried to score a competitive advantage on the lines of quality and technology

Differentiation Across the Consumption Chain

A research finding suggests that there are one million branded products in the world today. As a result, the market is increasingly competitive and confusingly crowded.

For the customers, it means more choices than they know how to handle and less time than they need to decide. For the marketers, it is hyper-competition and continuous struggle to win the attention and interest of choice-rich, price-prone customers. The tyranny of choice for the buyers are represented by the following facts:

- An average hypermarket stocks 40,000 brand items (SKUs)

- An average family gets 80% of its needs met from only 150 SKUs

- That means there’s a good chance that the other 39,850 items in the store will be ignored

The implication is that those that don’t stand out will get lost in the pack! The average customer makes decisions in more than 100 product/service categories in a given month. He/she is exposed to more than 1600 commercials a day. Of this, 80 are consciously noticed and about 12 provoke some reaction.

The challenge for marketers is: how to get noticed (i.e. differentiation) and be preferred (i.e. positioning)?

Most profitable strategies are built on differentiation (i.e.) offering customers something they value that competitors don’t have. A close look at consumer behavior reveals that people buy on the differences. An ability to create compelling differences remains at the heart of a firm’s competitive advantage. The battle has always been (and still is) about differentiation - create winning differences in customers’ minds.

People pay attention to differences (though at different levels) and tend to ignore undifferentiated products. Here is an example of how Nike (the top-dog sports shoe brand) creates winning differences at cognitive, normative and wired-in levels in the buyer.

- Cognitive (conscious decisions) Level ‘I buy Nike because it’s made of engineered materials which enable higher athletic performance ’

- Normative (semiconscious feelings) level ‘I buy Nike because it’s “in” with my crowd’

- Wired-in (subconscious determinants) level (‘ Nike appeals to my desire to be cool, fashionable, strong, aggressive … ’)

Organizations use several differentiation dimensions. The most popular are product differentiation, service differentiation, personnel differentiation, channel differentiation and image differentiation.