Changing Structure of the Global Economy

- Details

- Category: Macroeconomics

- Hits: 10,687

In the postcrisis environment, issues of sustainability in the trajectory of the U.S. economy have come to the fore. Among the problems pointed to are a large current account deficit, the paucity of household savings, overleveraging in the financial and household sectors, and stagnation of middleclass incomes.

However, what appears missing is a detailed look at the structural shifts in the economy over longer periods, and the way in which the emerging economies’ growth is affecting the pattern of industry employment and value added in the United States. This paper attempts to close the gap, offering a fresh look at the U.S. economic structure over the past twenty years and exploring the implications of such shifts.

The American economy does not exist in a vacuum; some of its most striking evolving characteristics are tied to long-term trends in the developing world and especially the large emerging economies. The first section describes the evolving structure of the global economy and offers perspective on how emerging economies have increased their influence on the U.S. economy since the early 1950s.

The next section describes the tradable and nontradable parts of the economy. It then looks at the trends in employment, value added, and value added per employee across industries in the tradable and nontradable sectors of the economy. The paper concludes with an assessment of the structural and employment challenges and begins a preliminary exploration of possible policy responses.

The main body of the paper is a detailed and data-intensive look at changes in employment and value added in U.S. industries. Readers interested in the major trends and findings should read the executive summary and the evolving structure of the global economy, and then the last four sections, starting on page 32, which discuss policy responses that may help shift the trajectory.

Changing Structure of the Global Economy

Since the end of World War II, the global economy has steadily increased its trade and financial openness, enabled in part by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), now the World Trade Organization (WTO). In parallel, colonialism, with its inherent constraints on economic development and its built-in asymmetries, collapsed.

Although two hundred years behind the advanced countries, whose growth accelerations began in the late eighteenth century with the British industrial revolution, developing countries across the globe began a century-long process of modernization. We are slightly more than halfway through that century.

As formal barriers to trade and capital flows declined, a number of other trends combined to accelerate the growth and structural changes in the developing economies. They included advances in transportation and communications technology, management innovation in multinational companies, a process of learning about doing business in multiple and diverse environments, and the integration of multinational supply chains.

Thanks to information technology, services formerly in the nontradable part of the economy, from radiology to accounting and IT servicing, have become tradable. Large emerging economies, with varying starting points (and many false starts), have accelerated to sustained growth rates, often exceeding 7 percent a year. After several decades of high-speed growth, these economies have become larger and richer.

An essential ingredient in that growth is structural change. With increases in size, the shifting structures of emerging markets have larger impacts on the structures in advanced countries. A growing emerging economy shifts to higher value-added components of international supply chains as physical, human, and institutional capital deepen and emerging economies begin to compete directly with rich ones.

In the early part of the postwar period, as successive rounds of the GATT agreement removed restrictions on manufacturing exports, developing countries—whose exports consisted mainly of natural resources and agricultural products—expanded into labor-intensive and lower value-added manufactured goods. Textiles and apparel production were prominent. Other industries were added as time progressed. The list is almost endless: luggage, dishes, cutlery, toys, personal products, and so on.

But it was not just finished products that were added to emerging economy portfolios. Laborintensive and relatively low value-added parts of global supply chains moved to emerging economies as multinational companies progressively learned how to integrate geographically dispersed operations efficiently. In consumer electronics, the labor-intensive assembly process is a natural fit for lower-income countries.

Semiconductors, circuit boards, and other components are designed and manufactured elsewhere, namely in high-middle-income or high income countries such as South Korea and Japan. Branding, marketing, and research tend to be done in rich countries. Each component of the supply chain has its most cost-efficient location.

The shape of global supply chains is constantly shifting. Countries enter and engage with the global economy at different times and expand at different rates. The early high-growth economies— Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan—initially exported labor-intensive products, then graduated to more capital-intensive products such as automobiles and motorcycles, and then to human capitalintensive activities such as design and technology development.

The labor-intensive activities, which these early high-growth markets exited as their costs of labor rose, moved to later arrivals in the global economy, predominantly Asian economies such as China and Vietnam. The shifting global structure is not static, cyclic, or mean-reverting. It is best described as a journey that will only be taken once. Late arrivals to industrialization tend to follow the same path as earlier ones.

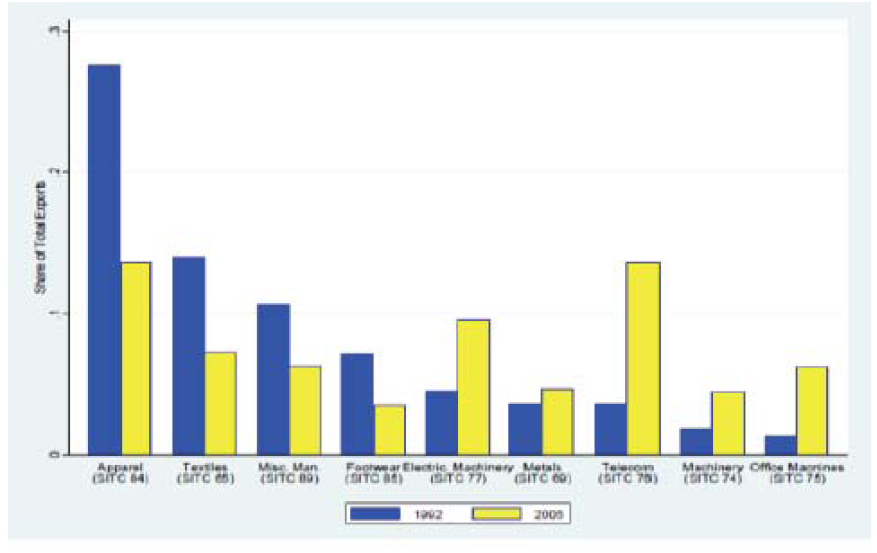

After thirty years of very high growth, the structure of China’s economy is shifting as Japan’s and South Korea’s did before it. The pattern of diversification is evident in figure

Figure 1. Reallocation of Manufacturing Exports in China across Major Two-Digit Sectors

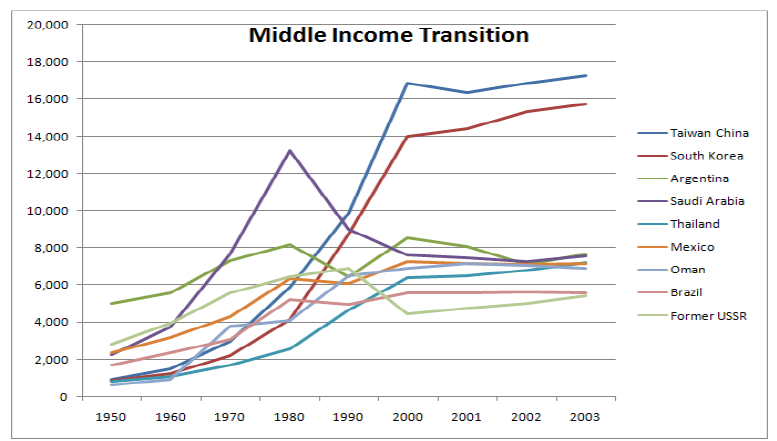

China, with a per capita income of about $3,800, is now entering what is called the middle-income transition. This phase of development is sometimes called a trap. It is one of the more complex and risky transitions that occur in developing countries on the long, multidecade journey from lowincome to advanced country levels. The evidence we have from the postwar history suggests that the majority of countries entering the middle-income transition have slowed significantly or even stalled.

Of the sustained high-growth cases in the postwar period (thirteen, soon to be fifteen, with the addition of India and Vietnam), only five have maintained high growth rates through the middle-income transition and proceeded toward advanced country income levels of $20,000 per capita or above (see figure 2). Those high-speed transitions occurred in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore.

Figure 2. Real Per Capita GDP and the Middle-Income Transition

Tradable and Nontradable Sectors

In the global economy, some goods and services trade internationally and some do not. The tradable sector consists of the goods and services that can be produced in one country and consumed in another, or, as in tourism or education, consumed by people from another country. The nontradable sector is the set that must be produced and consumed in the same country. Examples of tradable goods and services include most manufactured products, many agricultural products, a growing set of business services and technical services, minerals, energy, and gas.

The nontradable sector includes government, retail, health care, construction, hotels and restaurants, most legal services, and so on. The boundary between the tradable and nontradable sectors is not fixed. Twenty-five years ago, business services such as information technology (IT) maintenance and support were not traded internationally; now Internet connectivity and innovative software permits many of these services to be performed remotely at lower cost, often in another country.

Over time, cross-border specialization and learning brings higher quality and efficiency as well as lower cost. Tradable and nontradable parts of the economy do not line up perfectly with conventional industry definitions. The latter are groupings of industries based on final products. Some of these products within a particular grouping may be tradable internationally but others not tradable. For example, most legal services are not tradable internationally, but a subset dealing with international business and financial transactions are.

But far more important than comingling of tradable and nontradable products within an industry group is another phenomenon altogether. A good or service is produced and delivered to the final consumer in a series of steps called the value-added chain.

Total value added is defined as the final sales of a company or industry less its purchase inputs (excluding labor and capital). Purchases would include services such as legal services and accounting services, as well as parts and components made by other industrial sectors (or companies), and raw materials, energy, and the like.

The idea is that labor (of all kinds, including management) and capital combine to add value to the purchased inputs, and that value is reflected in the sales value of the final output. If the final output (a good or service) is not sold, as in the case of most of government, there is no market mechanism for determining value of output.

The final output is then taken to be the total cost of labor, capital (annualized) and the purchased inputs, including intermediate products and services. The idea is that the democratic collective choice mechanism that replaces the market works reasonably well and incurs these costs because the society places at least this much value on the services that are delivered. Of course, one can and people frequently do question that. But, in any case, that is the value-added calculation for services that are delivered but not sold.

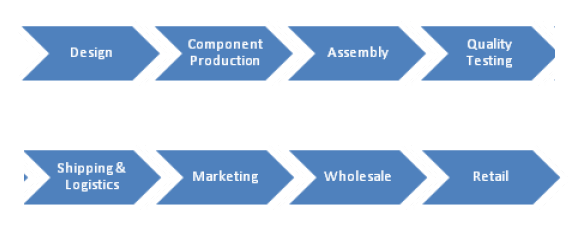

To illustrate what a value-added chain might look like, imagine that we are planning to launch a new electronic product. From initial design to store sales are a multitude of steps that must be taken, each of which can be broken down into smaller steps and processes (see figure 3). In sum, these steps form the value-added chain. The value added for the final product would be the retail price (complete with markups) less all the costs that went into getting it into the consumer’s hands (excluding labor and capital).

Figure 3. Value-Added Chain for an Imaginary Electronic Product

The details and number of steps vary across industries. When viewed this way, manufacturing, in the sense of production of a commodity, is not a single industry. It is a subset of the steps or stages in the value-added chain, and often, for complex products like autos, more than one stage.

Complex value-added chains usually include both tradable and nontradable components. Just as industry data do not capture these complexities, trade data also have shortcomings. An iPad shipped from Foxconn in China has value-added components from the United States and several countries in Asia embedded in it. Without a large amount of supplementary information, it is effectively impossible to track back from the consuming country to find the locations of the creation of value added for a particular product. Moreover, the value-added chains for final products can overlap.

Some parts of the chain are specific to the particular product (assembly, for example), whereas others can be shared (component parts or logistics or back office functions). The global economy does not divide neatly into totally separate value-added chains with one for each industry or class of final products. Part of the tradable sector is a set of functions that involve information processing and services related to them.

These sectors have been the subject of numerous studies and much attention. Important technological innovations have enabled labor savings in information processing, and transactions automation. In addition, some of these functions have been outsourced. The evidence thus far appears to favor the conclusion that much of the employment reduction has been the result of laborsaving technology rather than of outsourcing.

However, some analysts confuse these sectors with the entire tradable sector, and conclude that globalization has had relatively small impacts until now. The premise is inaccurate and the conclusion false. Information processing and related services are a small, growing part of trade. It is interesting, relatively new, and the studies are useful.

But one should not draw broad conclusions about the impact of the integration of global markets from analyses of one relatively small part. As we shall shortly see, employment is declining in manufacturing and rising in finance. Both groups outsource and offshore information services. But to conclude that the manufacturing employment decline can be attributable to an unusually large impact on those sectors from information processing outsourcing or labor savings transactions automation, is simply incorrect.

To summarize, the best way to think about the tradable sector of an economy is to define it as the set of activities that can be part of global supply chains. At this stage, we have data on industries. So, as a first approximation, we will classify goods and services (that is, industries) proportionately as tradable and nontradable depending roughly on the tradable proportion of the value-added chain (using value added as the measure).