Global Supply Chain Operations

- Details

- Category: Supply Chain Management

- Hits: 18,206

To date, our world market is dominated mostly by many well established global brands. Over the last three decades, there has been a steady trend of global market convergence – the tendency that indigenous markets start to converge on a set of similar products or services across the world. The end-result of the global market convergence is that companies have succeeded in their products or services now have the whole wide world to embrace for their marketing as well as sourcing.

The rationale of global market convergence lies partially in the irreversible growth of global mass media including the Internet, TVs, radios, newspapers and movies, through which our planet has become truly a small global village. Everybody knows what everybody else is doing, and everyone wants the same thing if it is perceived any good. It also lies in the rise of emerging economic powers led by BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India and China), which has significantly improved the living standard and the affordability of millions if not billions of people.

For organizations and their supply chains, the logic of going global is also clearly recognizable from the economic perspective. They are merely seeking growth opportunities by expanding their markets to wherever there are more potentials for profit-making; and to wherever resources are cheaper in order to reduce the overall supply chain costs. Inter-organizational collaborations in technological frontier and market presence in the predominantly non-homogeneous markets can also be the strong drivers behind the scene.

One can also observe from a more theoretical perspective that the trends of globalization from Adam Smith’s law of “division of labor”. A global supply chain is destined to be stronger than a local supply chain because it takes advantage of the International Division of Labour. Surely, the specialization and cooperation in the global scenario yields higher level of the economy than that of any local supply chains. Thus the growth of the global supply chain tends to give rise to the need for more coordination between the specialized activities along the supply chain in a global scale.

As the newly appointed Harvard Business School dean professor Nitin Nohria said “If the 20th century is American’s century, then the 21st century is definitely going to be the global century.” The shift of economic and political powers around world is all too visible and has become much more dynamic and complex. But, one thing is certain that there will be significantly and increasingly more participation of diverse industries from all around the world into the global supply chain network; hence bringing in the influences from many emerging economies around the world. Their roles in the globally stretched network of multinational supply chains are going to be pivotal and will lead towards a profoundly changed competitive landscape.

In such a global stage there are a number of key characteristics that global supply chains must recognize before they can steer through:

- Borderless: National borders are no longer the limits for supply chain development in terms of sourcing, marketing, manufacturing and delivering. This borderless phenomenon is much beyond the visible material flows of the globalized supply chain. It is equally strongly manifested in terms of invisible dimensions of global development such as brands, services, technological collaboration and financing. Evidently, the national borders are far less constrictive than they used to be. Arguable this is perhaps the result of technology development, regional and bilateral trade agreements, and the facilitation or world organizations such as WTO, WB, GATT, OECD, OPEC and so on.

- Cyber-connected: The global business environment is no longer a cluster of many indigenous independent local markets, but rather it emerged as an inter-connected single market through predominantly and growingly important cyber connections. For this reason, the interconnection of our global business environment is almost “invisible”, spontaneous and less controllable and surely irreversible. Globally stretched multinational supply chains would not be possible or even comprehensible without cyber-technology allowing large amounts of data to be transferred incredibly quickly and reliably.

- Deregulated: Trade barriers around the world has been demolished or at least significantly lowered. Economic and free-trade zones around the world have promoted open and fair competition and created, albeit never perfect, a level playing field on the global stage. Deregulation simplifies and removes the rules and regulations that constrain the operation of market forces. It has targeted more at international trading and aiming for stimulating global economic growth. The typical deregulated regions are European Union, North America Free Trade Agreement zone; Associations of Southeast Asian Nations group and so on. Deregulation reduces government control over how business is done thus moving towards laissez-fair and free-market systems.

- Environmental Consciousness: Last decade has witnessed the growing concerns on the negative impact of business and economic development on the natural environment. The global movement towards green and more eco-sustainable business strategies plays an important role in today’s global supply chain development. This is also driven by the actions of lawmakers and regulatory agencies, such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Governments of leading economies are increasingly involved in promoting greening activities in business, and formalize more legislation and regulation to place upon firms in the future. A carbon footprint is now a key performance measure of sustainability for many global supply chains.

- Social Responsibility: Along with that is a wider socio-economic impact. Fairtrade and business ethics become increasingly the key measures on a business’s social responsibility and the key factors for business decision making. Social pressure strikes at the heart of a company’s brand in the mind of the consumer. A significant group of consumers have begun making their purchasing decisions based on the supply chain’s ethical standard and social responsibility. Global corporate citizenship and social responsibility forms yet another important business environmental factor that can make or break a business.

Strategic Challenges

Under such a changing global business environment, what are the new strategic and operational challenges? At a macro level, there are at least five key strategic challenges that will have the long term and overall impact on the architecture as well the management process of the global supply chains. Those strategic challenges tend to be interrelated intricately and dynamically with one another. The magnitude of those challenges varies from industry to industry; and from time to time.

Market dimension

Continuing demand volatility across the world market has hampered many supply chains’ ability to manage the responsiveness effectively. Demand fluctuation at the consumer market level poses a serious challenge to the asset's configuration of the supply chain, capacity synchronization, and lead-time management. More often than not it triggers the ‘bullwhip effect’ throughout the supply chain resulting in higher operating cost and unsatisfactory delivery of products and services.

The root causes of the demand volatility in the global market are usually unpredictable and even less controllable. Economic climate plays a key role in overall consumer demand. The recent worldwide economic downturn has made many global supply chains over-capacitated, at least for a considerable period of time. Geo-political instability around the world has also contributed to market volatility to certain industries.

Technology development and product innovation constantly create as well as destroys the markets often in a speed much faster than the supply chain can possibly adapt. Emerging economies around the world are aggressively churning out products and services that rival the incumbent supply chains in terms of quality and price, which lead to huge swings of market sentiment.

Recent research shows that customer loyalty has significantly decreased over the last decade, adding to the concerns of market volatility. The development of internet-based distribution channels and other mobile marketing media has made it incredibly easier for consumers to switch their usual brands. Many products are becoming more and more commoditized, with multiple competitors offering very similar features. With increased market transparency, many B2B and end customers simply shop for the lowest price, overlooking their loyalty to particular suppliers or products. A lack of robust forecasting and planning tools may have contributed to the problem, as companies and their suppliers frequently find themselves scrambling to meet unexpected changes in demand.

Technology dimension

Technology and the level of sophistication in applying the technology for competitive advantages have long been recognized as the key strategic challenges in supply chain management. This is even more so, when we are now talking about the supply chain development in a global stage. The key strategic challenges in the technological dimension are threefold.

The first is the development lead-time challenge. The lead-time from innovative ideas to testing, prototyping, manufacturing, and marketing has been significantly shortened. This is partially due to the much widened global collaboration on technological development and subsequent commercialization and dissemination. The globally evolved technology development systems have created a new breed of an elite group as the world technology leaders across different industries.

They capture the first-mover advantages and made the entry barriers for newcomers almost impossible to overtake. No doubt, there is a strategic challenge that the global supply chain must create an ever-ready architecture that can quickly embrace the new ideas and capitalize it in the market place.

The second challenge comes from its disruptive power. Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen published his book The Innovator’s Dilemma in May 1997, in which he expounded on what he defined as the disruptive technology.

The basic message he tried to put across was that when new technologies cause great firms to fail, managers face the dilemma. Evidently, not all new technologies are sustaining to business, often they are competency-destroying. The product or service developed through applying new innovative technologies may not be so much appreciated by the consumers.

Consumers often are often not so eager to buy the ideas. They may not be so convinced that the value the technology created or the costs it added in. If you wait for other companies to test the market first, then you run a high risk of losing the first-mover advantage and losing market leadership. That’s the dilemma and that’s the challenge.

The third challenge lies in the supply chain network. The innovative ideas and new technologies usually emerge from a supplier or a contractor in the supply chain network. To convince the whole supply chain of the value-adding or cost reduction is not guaranteed. Each supplier and contractor will have its own value stream and will make technology adoption decisions based on the needs of its own customers. Innovative ideas that come up from subcontractors may be stifled due to the supply chain’s inability to coordinate value contribution between individual members and the whole supply chain.

The cost and profit structures in the value network can also limit the attractiveness of an innovation. If profit margins are low, the emphasis will be on cost-cutting across proven technologies, rather than taking the risk of the new technologies.

Finally from the technology evolution perspective, technology destroys as readily as it creates. The development of digital photography has literally destroyed the photo film manufacturing industries including many well-known brands; LCD and Plasma technology also smashed the TV Tube (traditional screen component) manufacturing industry overnight.

This increased risk of technology disruption at the industrial scale is lot more formidable than the innovative dilemma Prof Christenson was talking about in his book. Nevertheless, there are some helpful supply chain strategies that can better prepare them for the eventuality.

Resource dimension

From the resource-based perspective, global supply chain development is both motivated by dinging new resources around the world and by make better use of its own already acquired resources to yield economic outputs. It comes as no surprise that one of the key strategic challenges in global supply chain development is about resource deployment. The term resource in this context means any strategically important resources, including financial resources, workforce resource, intellectual resource, natural material resources, infrastructure and asset-related resources, and so forth.

Stretching supply chains’ downstream tentacles around the world opens the door for making good (more efficient) use of internal resources, i.e. the same level of resources can now be used to satisfy much wider and bigger market in terms of volume, variety, quality and functions. However the internal resource or competency-based strategy will also face more severe challenges on the global stage than in its own local or regional market.

The challenges are not necessarily just from the indigenous market, but more likely they come from equally competitive incumbent multinationals and possible emerging ones alike. Also more menacingly the internal based advantages can evaporate anytime when global business environment subjects fundamental changes.

Stretching the sourcing-end (supply side) of the supply chain to the global market is a great strategy to acquire scarce resources, or any resources at a much-lowered cost. The productivity and operational efficiency-oriented strategy is often no match to the procurement focused strategy in measures of reducing the total supply chain cost. No wonder many multinationals are actively debating on sourcing their workforce, materials and energy from overseas locations in order to significantly reduce the operation cost, which will then lead to more competitive market offerings.

This resource sourcing strategy has been the prime drive for the surge of off-shoring and outsourcing activities all over the world. However many long-term and short-term impacts of outsourcing and off-shoring are difficult to be fully understood from the outset, if at all possible. Thus it forms a key strategic challenge in global supply chain development.

Time dimension

Most of the key global supply chain challenges are time-related, and it appears to be that they are becoming even more time related than ever before. Given that everything else is equal; the differences on time could make or break a supply chain. When the new market opportunity emerges it is usually the one who gets into the market first reaps the biggest advantages. Competitions on many new electronic consumer products is largely about who developed it first and become the industry leader.

From the internal supply chain perspective, the cost and core competencies are all largely measured against time. Inventory cost increase, if the materials do not move on quick enough; supply chain responsiveness is can be significantly influenced by the lead-time and throughput time.

Indeed, one of the key supply chain management subject areas is about agility and responsiveness. That is basically defined as how fast the supply chain can respond to the unexpected and often quite sudden changes in market demand.

Understandably, in the increasingly fast-moving global market place, developing and implementing an agile supply chain strategy makes sense. However, the tough challenges are usually not on making the decisions as to whether should the supply chain be agile or not. They are more on balancing the ‘cost to serve’. In order to maintain a nimble-footed business model, the supply chain may have to upgrade its facilities with investment, having higher than usual production and service capacities, or having high level of inventories. Then the question is would the resultant agility pay for the heightened supply chain costs. There is no fixed answer to this question, and it remains as a key challenge to supply chain managers.

The time measures on many operational issues have also been the major challenges for supply chain managers. Customer lead-time, i.e. from customer order to product delivery, is one of those challenges. Toyota claims that they can produce a customer-specified vehicle with a fortnight – the shortest lead-time in the auto industry. This adds huge value to the supply chain in terms of customer satisfaction, cost reduction, efficiency and productivity. But it could be a huge challenge, when the customers are all over the world and the production sites and distribution logistics facilities are not well established.

All the challenges in the three dimensions are, of course, interrelated and even interdependent with each other. A supply chain strategist must have a sound system view to understand the intricate relations of all factors in the whole supply chain and over the projection of the long-term. Those strategic challenges have undoubtedly given rise to the risk level of global supply chain development. It came as little surprise that the supply chain risk management, which will be discussed later in this book, is now one of the hot topics discussed in the academic and business circle alike.

How Global Supply Chains Responded

Knowing the challenges is one thing perhaps to begin with, but learning about how to face up to the challenges is quite another. Despite the plethora of literature on supply chain management, there are still no universally agreed “one size fit all” recipes for managers to prescribe in order to survive the challenges. Academic and empirical studies show there are at least five common approaches that supply chains have survived the global challenges.

Collaboration

“If you cannot beat them, you better join them.” A great deal of global supply chain management activities are not necessarily about competing against one another, rather it is more about collaboration and partnering. Inter-firm collaboration in the supply chain management context is simply defined as working together to achieve a common goal. The content of collaboration varies from project to project and from business to business.

It may be a research and development collaboration which is aiming perhaps for a technological advancement or a new product design, or it could be a logistics operational collaboration where the aim is to reduce logistics lead-time and cost; it could also be marketing collaboration where the aim is to penetrate the market and increase sales. So, the collaboration is usually mentioned when there is an area or a project the activities of the collaboration can be associated with. The parties involved in the collaboration are often referred to as the partners or collaborative partners.

There are a number of obvious reasons why collaboration is one of the most favorite supply chain management approaches.

- Sharing resources: collaboration between two firms helps to share the complementary resources between them, thus avoiding unnecessary duplication of the costly resources such as capital-intensive equipment, service and maintenance facilities, and distribution networks and so on. Information, knowledge and intellectual resources are also very common resources that are shared during the collaboration.

- Achieve synergy: the collaboration of the two partnering firms will usually result in what is called ‘synergy.’ Synergy, in general, may be defined as two or more things functioning together to produce a result not independently obtainable. That is, if elements A and B are combined, the result is greater than the expected arithmetic sum A+B. In the context of business collaboration or partnering, synergy is about creating additional business value that neither can achieve individually.

- Risk-sharing: a properly constructed collaboration can help to mitigate the company’s market and supply risk significantly for both parties. Risk is the negative but uncertain impact on business, which is normally beyond control. By collaborating on investment and marketing, the negative impact of the supply chain risks can be borne by both parties and thus shared and halved.

- Innovation: collaboration in technology development and R&D partnering is a particularly effective way to advance their competitive advantages through innovation in the technological frontier. The logic behind is perhaps that when people from different businesses working to gather, they start to blend their knowhow and experience together, sparkling new innovative ideas. In most of innovation training programs, one can always recognize one of the steps of generating innovative ideas is to have brainstorming across a multifunctional team.

Supply chain integration

The nature of a supply chain is that it is usually a network which consists of a number of participating firms as its member. For a global supply chain the network stretches many parts of the world, and the participating member firms of the network can be an independent company in any country around the world. Supply chains are therefore voluntarily formed ‘organizations’ with fickle loyalties and often antagonistic relations in between the member firms. Communication and visibility along the supply chain are usually poor. In other words, supply chains are not born integrated.

Supply chain integration, therefore, can be defined as the close internal and external coordination across the supply chain operations and processes under the shared vision and value amongst the participating members. Usually, a well-integrated supply chain will exhibit high visibility, lower inventory, high capacity utilization, short lead-time, and high product quality (low defect rate). Therefore, managing supply chain integration has become one of the most common supply chain management approaches that can stand up to the global challenges.

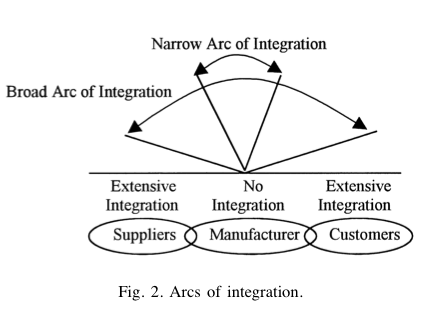

However, there is no supply chain that is strictly 100% integrated, nor anyone that is strictly 0% integrated. It is about how much the supply chain is integrated from a focal company’s point of view. To illustrate this degree of difference in supply chain integration, Frohlich and Westbrook (2001) suggested a concept of ‘Arc of Integration’ (Figure 3). A wider arc represents a higher degree of integration which covers a larger extent of the supply chain, and a narrow one for a smaller extent. The issue of supply integration is particularly important when the supply chain is formed by members around the globe.

Figure 3. Arc of integration (Source: Frohlich and Westbrook, 2001)

Divergent product portfolio

Conventional wisdom says that ‘don’t put all your eggs in one basket.’ It also makes sense in formulating a global supply chain development strategy. Translated into business management terminology, the wisdom is very similar to the ‘divergent product portfolio’ strategy. Then it may make even more sense when the global market becomes the stage for the supply chain. Two key characteristics of the global market are volatility and diversity.

Develop a divergent product portfolio will make the supply chain more capable of satisfying the divergent demand of the world market. Many leading multinational organizations have already been the firm believer of this strategy. They have developed a wide range of products or even business sector portfolios to cater to the market needs. Virgin Group, General Electric, British Aerospace are just some well-known examples.

The divergent product portfolio strategy can also significantly mitigate the market risks that brought forth by the nature of global market volatility. If one product is not doing well, the supply chain can still be stabilized by others that do well.

The shock of one single market at a particular time will not derail the overall business. In the long run, occasional market instabilities will ease off with each other. So, the divergent portfolio works as a shock absorber and risk-mitigating tool.

Develop the “blue ocean strategy”

Instead of going for the ‘head-on’ competition in the already contested ‘red sea’ a much more effective approach is to create a new market place in the ‘blue ocean’, which makes the competition irrelevant. This is an innovative strategic approach developed by Prof. Cham Kim and Renee Mauborgne in 2005, and published in their joint authored book “Blue Ocean Strategy”. In the book, the authors contend that while most companies compete within such red oceans, this strategy is increasingly unlikely to create profitable growth in the future.

Based on a study of 150 strategic moves in many globally active supply chains over the last thirty years, Kim and Mauborgne argue that developing the ‘blue ocean strategy’ (as they coined it) has already been proven an effective response to the global challenges for many supply chains. Tomorrow’s leading supply chains will succeed not by battling competitors, but by creating ‘blue ocean’ of uncontested market space that is ripe for growth. They have proved that one can face up to the challenges most effectively without actually doing so. Creating a new market space is actually a lot easier than you think if you know-how.

Pursuing world-class excellence:

To weather the global challenges and to achieve long-lasting business success often calls for one fundamental feat and that feat is world-class excellence. Almost all known world-leading supply chains in all industrial sectors have somehow demonstrated that they have just been excellent in a multitude of performance measures.

The world-class excellence defines the highest business performance at a global level that stand the test of time. Only the very few leading-edge organizations around the world truly deserve this title. But the title is not just a title. It is the fitness status that ultimately separates the business winners from losers.

To become a world-class supply chain one needs to excel in four dimensions. The first dimension is operational excellence.

All world-class supply chain must have optimized operations measured in productivity, efficiency, cost-effectiveness, quality, high standard of customer service and customer satisfaction. The second dimension is the strategic fit. All world-class supply chains must also ensure that excellent operations fit to the supply chain’s strategic objective and stakeholder’s interests, and the internal resources fit the external market needs. The third dimension is the capability to adapt.

Would class supply chains must be dynamic and able to adapt to a new business environment in order to sustain the success. The fourth dimension is a unique voice. All world-class supply chains need to develop its own unique signature practices that render positive market results. Such an internally unique practice coupled with the positive market result is called a unique voice. This dimension goes beyond benchmarking on best-practices; it creates best-practices (Lu 2011).

Current Trends in Global SCM

Many reliable management researches and surveys conducted in recent years have come to a broad consensus that some significant development trends are shaping and moving today’s global supply chains. The following trends are mainly based on and adapted from the PRTM 2010 Survey results with the author’s own interpretation and analysis to facilitate student learning.

Trend 1: Supply chain volatility and market uncertainty is on the rise.

Research survey shows that continued demand volatility in most of the global markets is a major concern to the executives of supply chains. Significantly more than any other challenges to supply chain flexibility, more than 74% of the surveyed respondents ticked the demand volatility and poor forecasting accuracy as the increasing major challenges to supply chain flexibility. Apparently, few companies have strategies in place for managing volatility in the years ahead let along implementing it. The lack of flexibility to cope with the demand change is increasingly a management shortfall. In the path of economic recovery, this shortfall could well be the trigger for bullwhip effect.

The fast development of the cyber market and mobile media has given rise to the market visibility leading to high level of market transparency. B2B customers and consumers have found it a lot easier to shop for alternative lower price or better value. The switching cost is evaporated rapidly, and so is customer loyalty, which adds salt to the injury. The only known approaches to deal with the trend of increased volatility are improving forecasting accuracy and planning for flexible capacity throughout the supply chain. Best performing companies tends to improve supply chain responsiveness through improving visibilities across all supply chain partners. On the downstream side, companies are now focusing more on deepening collaboration with key customers to reduce unanticipated changes.

Trend 2: Market growth depends increasingly on global customers and supplier networks

The research survey has shown a positive growing trend in international customers and international suppliers in more international locations. As a result, more than 85% of companies expect the complexity of their supply chains to grow significantly at least for the coming year. The immediate implication of this trend is that the supply chain will have to produce higher number of products or variants to fulfil the customer expectations, albeit this may vary slightly for different geographical regions. In the main, the pattern of global supply chain is going to be more complex in terms of new customer locations, market diversity, product variants, and demand volatility.

On the supply side, the trends indicated that more dynamic supply networks stretching far and wide globally. Managing those suppliers, developing them and integrating them become more a critical challenge than ever before. Nearly 30% of respondents expect the in-house manufacturing facilities will decline and to be replaced by outsourced and off-shored international contractors. Similarly nearly 30% of respondents expected a decline in the number of strategic suppliers to the OEM (original equipment manufacturer) in order to achieve more closely integrate the supply chain for higher collaborated value adding. This will result in more consolidated supply base. This is more evident in North America and Europe, but significantly less so in Asia where expansion of supply network is more of the case.

Trend 3: Towards more cost-optimized supply chain configurations

Survey respondents seemed confident that they will be able to deliver substantial gross margin improvements over the next couple of years. However the gains will not come from price increases, but from reductions of end-to-end supply chain costs. Globalising supply chain operations and outsourcing specific functions are viewed as critical for controlling costs. It came as no surprise that outsourcing is on the rise across many industrial sectors around the world. Companies are taking advantage of lower costs in emerging markets and increasing the flexibility of their own supply chain. The functions that will see the greatest increase in outsourcing are product development, supply chain planning and shared services.

However, globalization does not seem to have reduced process and management costs. In fact those hidden costs could be on the rise when the supply chain becomes more global if not careful. Leading companies understand the impact of those hidden costs and are taking aggressive steps to identify and manage them.

Many are embracing new concepts like Total Supply Chain Cost Engineering, an integral approach to calculating and managing total cost across all supply chain functions and interfaces. Rigorous cost optimization across the end-to-end supply chain – from order management, sourcing, and manufacturing to logistics and transportation – are critical for success.

Trend 4: Risk management involves end-to-end supply chain

To date, risk has become an increasingly critical management challenge across the global supply chains. According to the research survey participants, new demands from their customers have played a key role in this development. Dealing with cost pressures of their own, many customers have increased their efforts in asset management and have started shifting supply chain risks, such as inventory holding risks, upstream to their suppliers.

This approach, however, merely shifts risks from one part of the supply chain to another but not reduces it for the whole supply chain. In fact, between 65% and 75% respondents believe that supply chain risks can only be most effectively mitigated by the end-to-end supply chain approaches. These end-to-end supply chain practices include advanced inventory management, joint production and material resource planning, improved delivery to customers and so forth.

Leading companies are taking an end-to-end approach in managing risk at each node of the supply chain. To keep the supply chain as lean as possible, they are taking a more active role in demand planning, which ensures they order only the amount of material needed to fill firm orders. Firms are also limiting the complexity of products that receive late-stage customization. Leading companies mitigate inventory-related risks by shifting the responsibility for holding inventory to their suppliers and, furthermore, by making sure finished product is shipped immediately to customers after production.

Trend 5: More emphasis on supply chain integration and empowerment

Little can be achieved without appropriate management approaches that truly integrated across all functions throughout the supply chain and empowered them to take bold action. However, approximately 30% mention the lack of integration between supply chain functions like product development and manufacturing. Integrated supply chain management across all key functions still seen to be a myth, with many procurement and manufacturing executives making silo optimization decisions.

Nearly one-fourth of survey respondents point to their organizations' inability to make concerted actions and coordinated planning to respond to the external challenges. This could be a surprise to many that would believe after so much has been talked by so many for so long on the supply chain integration, little has been achieved in practice.

Whilst almost all the survey participating companies have supply chain departments, many of them failed to empower their supply chain managers to take leading roles in business transformation.

Leading companies understand that breakthrough improvements are not possible unless the decisions made are optimal for all supply chain functions. For this reason, they have already taken steps to integrate and empower their supply chain as a single resource under one joint responsibility. These firms are making sure the organization has a strong end-to-end optimization, and are integrating supply chain partners up and downstream.