The Labor Market

- Details

- Category: Macroeconomics

- Hits: 7,851

The labor market stands as one of the most critical components of any economic system, serving as the arena where employers seek workers and workers seek employment. Unlike markets for goods and services, the labor market involves human capital—the skills, knowledge, and abilities that individuals bring to their jobs. This unique characteristic makes the labor market particularly complex, as it is influenced not only by economic forces but also by social, political, and psychological factors.

In recent years, the labor market has undergone significant transformations due to technological advancements, globalization, demographic shifts, and most recently, the global pandemic. These changes have altered traditional employment patterns, job requirements, and the relationship between employers and employees. Understanding the mechanics of the labor market is essential for policymakers, business leaders, educators, and individuals navigating their careers in this evolving landscape.

Labor, alongside capital, stands as a fundamental building block of economic production and gross domestic product (GDP). The total amount of labor utilized in an economy during a specific period serves as a critical macroeconomic variable, directly influencing production capabilities, economic growth, and social welfare. Its relationship with unemployment rates makes it an indispensable metric for economic analysis and policy formation.

This article aims to provide a comprehensive examination of the labor market, exploring its structure, participants, equilibrium conditions, and the factors that influence its functioning. By delving into both macroeconomic and microeconomic perspectives, we will gain insights into how the labor market affects economic growth, income distribution, and overall social welfare.

What Is the Labor Market?

The labor market, at its core, is where labor services are exchanged. It represents the interaction between those offering labor services (workers) and those demanding them (employers). Unlike physical commodities, labor is inseparable from the individuals providing it, making the labor market uniquely human-centered.

Definition and Scope

The labor market encompasses all activities related to the buying and selling of labor services. This includes job searching, recruitment, hiring, promotion, retirement, and all other aspects of employment relationships. The scope of the labor market extends across different industries, occupations, skill levels, and geographical regions.

Labor markets can be classified in various ways:

- Geographical scope: Local, regional, national, or global labor markets

- Skill level: Markets for unskilled, semi-skilled, skilled, and highly specialized labor

- Industry-specific markets: Such as healthcare, technology, manufacturing, or service sectors

- Formal vs. informal: Regulated employment with contracts versus unregulated work arrangements

Historical Evolution

The concept of a labor market has evolved significantly throughout history. In pre-industrial societies, labor relationships were often governed by tradition, social hierarchy, or personal bonds. The Industrial Revolution marked a pivotal shift, creating wage-based employment and formalized labor markets.

The 20th century witnessed further transformations with the rise of labor unions, increased government regulation, and the growth of service-based economies. In the 21st century, digital platforms, remote work capabilities, and the gig economy have continued to reshape how labor markets function, creating more flexible but often less secure forms of employment.

Labor Market Structure

The structure of the labor market refers to its organizational characteristics, including the degree of competition, barriers to entry and exit, and the distribution of market power between employers and workers.

Types of Labor Market Structures

Perfect Competition

In a perfectly competitive labor market:

- Many buyers and sellers of labor exist

- Workers have homogeneous skills

- Perfect information about jobs and wages is available

- Workers and jobs are perfectly mobile

- No single employer or worker can influence wages

While purely perfectly competitive labor markets rarely exist in reality, some entry-level positions or standardized occupations may approximate this model.

Monopsony

A monopsony occurs when a single employer dominates the hiring in a particular labor market. This employer has significant power to set wages below competitive levels. Examples include:

- Company towns where one firm is the primary employer

- Specialized industries in isolated geographic areas

- Healthcare providers in rural areas who are the main employers of medical professionals

Oligopsony

An oligopsony exists when a small number of employers dominate a labor market. These employers may compete for workers but can still exercise significant influence over wages and working conditions. Examples include:

- University towns hiring academic professionals

- Technology clusters hiring specialized engineers

- Small towns with a few dominant employers

Monopoly and Bilateral Monopoly

Labor unions can create monopoly power on the supply side of labor markets by collectively representing workers. When a union negotiates with a monopsonistic employer, a bilateral monopoly emerges, with outcomes dependent on the relative bargaining power of each side.

Occupational and Industrial Segmentation

Labor markets are often segmented by:

-

Occupations: Different occupations have distinct skill requirements, training paths, and compensation structures. Professional occupations (doctors, lawyers, engineers) often have restricted entry through licensing and educational requirements.

-

Industries: Labor conditions vary significantly across industries due to differences in production processes, capital intensity, and market conditions. For example, manufacturing, healthcare, and technology sectors exhibit distinct labor market characteristics.

Dual Labor Market Theory

This theory suggests that labor markets are divided into:

- Primary markets: Characterized by stable employment, good wages, career advancement, and better working conditions

- Secondary markets: Featuring unstable employment, low wages, limited advancement opportunities, and poorer working conditions

Barriers between these segments often prevent workers from transitioning from secondary to primary markets, contributing to persistent inequality.

Labor Market Participants

Several key participants shape labor market dynamics:

Workers (Labor Supply): Individuals offering their time, skills, and effort in exchange for compensation represent the supply side of the labor market. Their decisions about whether to work, how many hours to offer, and what jobs to accept depend on factors including prevailing wages, working conditions, personal preferences, and alternative options.

Employers (Labor Demand): Organizations seeking workers constitute the demand side. Their hiring decisions are influenced by business conditions, productivity expectations, wage rates, and the costs associated with finding, hiring, and training employees.

Labor Market Intermediaries: These include employment agencies, job boards, professional recruiters, and educational institutions that facilitate matching between workers and employers, reducing search costs and information asymmetries.

Government and Regulatory Bodies: These entities establish and enforce labor market regulations, including minimum wage laws, workplace safety standards, anti-discrimination policies, and unemployment insurance programs. They significantly influence how labor markets function.

Labor Unions and Employer Associations: These organizations engage in collective bargaining and advocate for the interests of workers or employers, potentially influencing wage rates and working conditions beyond what individual market transactions might produce.

The labor market involves various participants, each with distinct roles, motivations, and constraints.

Workers/Labor Supply

Workers constitute the supply side of the labor market. Their decisions about whether to work, how much to work, and what type of work to pursue are influenced by:

Individual Factors

- Skills and education: Human capital investments determine productivity and earning potential

- Preferences: Personal values regarding work-life balance, job satisfaction, and working conditions

- Reservation wage: The minimum wage at which an individual is willing to accept employment

- Demographics: Age, gender, health status, and family responsibilities affect labor supply decisions

Collective Representation

Workers may organize collectively through:

- Labor unions: Organizations that negotiate wages, benefits, and working conditions on behalf of workers

- Professional associations: Groups that establish standards, provide certification, and advocate for specific occupations

- Worker cooperatives: Enterprises owned and democratically controlled by workers

Employers/Labor Demand

Employers represent the demand side of the labor market. Their hiring decisions are shaped by:

Business Factors

- Production needs: Labor requirements based on output goals and technology

- Cost considerations: Wages relative to worker productivity and other input costs

- Market conditions: Consumer demand for products and services

- Growth strategies: Expansion plans requiring additional human resources

Organizational Structures

Employers vary in their approach to labor relations:

- Corporate employers: From small businesses to multinational corporations

- Public sector: Government agencies at federal, state, and local levels

- Non-profit organizations: Entities with social missions rather than profit motives

Intermediaries

Various entities facilitate labor market transactions:

- Employment agencies: Organizations that match workers with employers

- Recruitment firms: Specialized companies that identify and screen candidates

- Job platforms: Digital marketplaces connecting job seekers with opportunities

- Educational institutions: Schools and universities that prepare individuals for labor markets

Government

The government plays multiple roles in labor markets:

- Regulator: Establishing labor laws, safety standards, and anti-discrimination policies

- Employer: Directly hiring workers for public service

- Policy maker: Implementing unemployment insurance, minimum wage laws, and training programs

- Information provider: Collecting and disseminating labor market data

Labor Market Equilibrium and Disequilibrium

The concept of equilibrium provides a framework for understanding how wages and employment levels are determined in labor markets. In theoretical terms, labor market equilibrium occurs when the quantity of labor demanded by employers equals the quantity supplied by workers at the prevailing wage rate.

Equilibrium Dynamics

In a simplified model, the equilibrium wage (W*) and employment level (L*) emerge from the intersection of:

- Labor demand curve: Depicting how many workers employers are willing to hire at different wage levels. This downward-sloping curve reflects the diminishing marginal product of labor.

- Labor supply curve: Showing how many workers are willing to work at different wage rates. This typically upward-sloping curve reflects workers' increasing reservation wages.

Labor markets, like other markets, tend toward equilibrium where supply meets demand, but various factors can create persistent disequilibrium conditions.

Wage Determination

In competitive labor markets, wages theoretically reflect the marginal productivity of labor—the additional output produced by one more unit of labor. However, actual wage determination involves:

Market Forces

- Supply and demand: The interaction between worker availability and employer needs

- Skill premiums: Higher compensation for scarce or specialized skills

- Compensating differentials: Wage adjustments for job characteristics (risk, unpleasantness)

Institutional Factors

- Minimum wage laws: Legal floors on wage rates

- Collective bargaining: Negotiated wage agreements

- Efficiency wages: Above-market wages to increase productivity or reduce turnover

- Wage norms: Industry standards and social expectations about fair compensation

Types of Unemployment

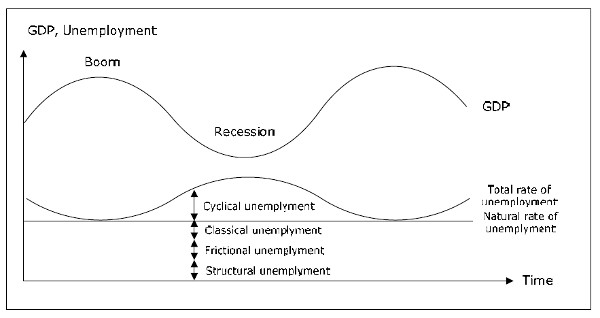

Figure 1: Different kinds of unemployment.

Labor market disequilibrium manifests in different forms of unemployment:

- Cyclical unemployment: Results from economic downturns and insufficient aggregate demand

- Structural unemployment: Occurs when workers' skills do not match available jobs

- Frictional unemployment: Arises during the natural process of job searching and matching

- Seasonal unemployment: Follows predictable patterns based on seasonal fluctuations in demand

Labor Surpluses and Shortages

Labor markets can experience:

- Labor surpluses: Excess supply of workers relative to available positions, leading to downward pressure on wages and increased unemployment

- Labor shortages: Insufficient workers to fill available positions, resulting in wage increases and potential production constraints

These imbalances can be economy-wide or concentrated in specific sectors, occupations, or regions.

Adjustment Mechanisms

Labor markets adjust to disequilibrium through various mechanisms:

- Wage adjustments: Changes in compensation to balance supply and demand

- Worker mobility: Geographic relocation or occupational switching

- Skills adaptation: Education and training to meet changing requirements

- Working hours flexibility: Adjustments in overtime, part-time work, or job sharing

- Immigration/emigration: Cross-border movement of workers

Labor Force Participation

Labor force participation reflects individuals' decisions to engage in the labor market, significantly affecting the overall supply of labor.

Labor Force Participation Rate

The labor force participation rate (LFPR) measures the percentage of the working-age population that is either employed or actively seeking employment. This key indicator provides insights into:

- Overall labor supply availability

- Demographic engagement with formal employment

- Potential for economic growth and fiscal sustainability

Determinants of Participation

Multiple factors influence individuals' decisions to participate in the labor market:

Economic Factors

- Wage levels: Higher wages increase the opportunity cost of not working

- Household income: Additional household earnings may reduce participation needs

- Job availability: Robust employment opportunities encourage participation

Demographic Factors

- Age structure: Different age cohorts have varying participation patterns

- Gender: Historical gender roles have affected participation, though gaps are narrowing

- Education levels: Higher education typically increases participation and earning potential

Social and Policy Factors

- Childcare availability: Accessible childcare facilitates participation for parents

- Retirement systems: Pension structures influence older workers' participation

- Disability policies: Support programs affect participation decisions for those with disabilities

- Cultural norms: Societal expectations regarding work and family roles

Trends in Participation

Labor force participation has undergone significant changes over time:

- Female participation: Dramatic increases in women's participation during the latter half of the 20th century

- Male participation: Gradual decline in prime-age male participation in many developed economies

- Youth participation: Decreasing rates due to extended education and training

- Older worker participation: Rising participation as longevity increases and retirement ages are extended

Contemporary Challenges

Current labor force participation challenges include:

- Skills mismatch: Gap between worker qualifications and job requirements

- Discouraged workers: Those who have stopped seeking employment due to perceived lack of opportunities

- Technological disruption: Automation and AI displacing certain types of work

- Work-life integration: Evolving preferences for flexible and remote work arrangements

Labor Market Flexibility and Rigidity

The degree of flexibility or rigidity in labor markets significantly affects their efficiency, adaptability, and equity outcomes.

Dimensions of Flexibility

Labor market flexibility encompasses multiple dimensions:

Wage Flexibility

- The ability of wages to adjust in response to changing economic conditions

- Influenced by minimum wage laws, collective bargaining, and wage-setting norms

Numerical Flexibility

- Employers' ability to adjust the quantity of labor through hiring and dismissals

- Affected by employment protection legislation and contractual arrangements

Functional Flexibility

- Workers' capacity to perform different tasks and adapt to changing requirements

- Dependent on training systems, skill transferability, and work organization

Working Time Flexibility

- Adjustability of hours worked, including part-time, flexible scheduling, and overtime

- Shaped by labor regulations and work-time agreements

Sources of Rigidity

Labor market rigidities may arise from:

Institutional Factors

- Employment protection legislation: Regulations governing hiring and firing practices

- Unionization: Collective agreements that standardize wages and working conditions

- Benefit systems: Unemployment insurance and social protection that affect work incentives

Structural Factors

- Skills specificity: Highly specialized skills that limit occupational mobility

- Geographic constraints: Housing costs, family ties, and regional disparities that impede relocation

- Information asymmetries: Incomplete knowledge about job opportunities and worker capabilities

Policy Approaches

Different policy approaches to labor market flexibility include:

Flexicurity Model

- Combines flexible labor markets with robust social security systems

- Emphasizes active labor market policies and lifelong learning

- Prominent in Nordic countries, particularly Denmark

Liberal Market Approach

- Minimal regulation of employment relationships

- Limited unemployment benefits with emphasis on rapid reemployment

- Characteristic of Anglo-Saxon economies like the United States

Regulated Flexibility

- Balanced approach with moderate employment protection

- Sector-specific flexibility arrangements through collective bargaining

- Common in continental European countries like Germany

Implications of Flexibility

The degree of labor market flexibility has significant implications:

- Economic performance: Potential trade-offs between efficiency and equity

- Worker security: Balance between employment stability and labor market dynamism

- Adaptation capacity: Ability to respond to technological change and economic shocks

- Income distribution: Effects on wage inequality and labor's share of national income

Macroeconomic Analysis of Labor Markets

Macroeconomic analysis examines labor markets at the aggregate level, focusing on economy-wide patterns and relationships.

Aggregate Labor Supply and Demand

Macroeconomic models analyze:

- Aggregate labor supply: The total hours people are willing to work at various wage levels

- Aggregate labor demand: The total labor hours employers wish to utilize at different wage rates

- Natural rate of unemployment: The level of unemployment consistent with stable inflation

Phillips Curve Relationship

The Phillips curve represents the historical relationship between:

- Unemployment: The percentage of the labor force without but seeking work

- Inflation: The rate of increase in the general price level

While originally conceived as a stable trade-off, modern understanding recognizes:

- Short-run trade-offs between unemployment and inflation

- Long-run independence of unemployment from inflation at the natural rate

- Expectations and structural factors that shift the curve over time

Business Cycle Effects

Labor markets respond distinctly to business cycle fluctuations:

During Expansions

- Decreasing unemployment rates

- Rising labor force participation

- Upward pressure on wages

- Increased job creation and labor demand

During Contractions

- Rising unemployment rates

- Declining or stagnant wages

- Reduced hiring and increased layoffs

- Potential decreases in labor force participation

Labor Market Indicators

Key macroeconomic indicators for labor markets include:

- Unemployment rate: The percentage of the labor force without jobs but actively seeking work

- Employment-to-population ratio: The proportion of the working-age population that is employed

- Labor productivity: Output per hour worked

- Labor cost indices: Measures of the cost of employing workers, including wages and benefits

- Wage growth: The rate of increase in nominal and real wages

Policy Instruments

Macroeconomic policies affecting labor markets include:

Fiscal Policy

- Government spending programs to create employment

- Tax policies that influence labor supply and demand

- Automatic stabilizers like unemployment insurance

Monetary Policy

- Interest rate adjustments affecting overall economic activity and job creation

- Inflation targeting with implications for real wages and employment

Labor Market Policies

- Active labor market programs for skills development and job matching

- Passive support through unemployment benefits and income maintenance

- Structural reforms addressing market inefficiencies

Microeconomic Analysis of Labor Markets

Microeconomic analysis examines individual labor market decisions, incentives, and outcomes at more granular levels.

Individual Labor Supply Decisions

Microeconomic models explore how individuals decide:

Hours of Work

- Trade-offs between labor and leisure

- Income and substitution effects of wage changes

- Backward-bending labor supply curve at high wage levels

Occupation Choice

- Expected lifetime earnings across different occupations

- Non-monetary aspects like working conditions and job satisfaction

- Investment in human capital and returns to education

Firm-Level Labor Demand

Employers make decisions based on:

Profit Maximization

- Hiring labor until the marginal revenue product equals the marginal cost

- Substitution between labor and capital based on relative prices

- Optimal combination of different types of workers

Human Resource Strategies

- Recruitment, retention, and compensation policies

- Training investments and skill development

- Work organization and productivity enhancement

Wage Differentials

Microeconomic analysis explains wage differentials based on:

Human Capital Theory

- Education and training investments create productivity differences

- Experience accumulation and on-the-job learning

- Signals of ability through educational credentials

Compensating Differentials

- Wage premiums for undesirable job characteristics

- Pay differences reflecting varying risk levels

- Non-wage benefits as part of total compensation packages

Discrimination

- Statistical discrimination based on group characteristics

- Taste-based discrimination reflecting prejudice

- Institutional barriers and occupational segregation

Efficiency Wage Theory

This theory explains why employers might pay above-market wages:

- Reducing turnover: Higher wages decrease costly worker departures

- Enhancing effort: Better compensation motivates greater productivity

- Attracting quality: Superior wages draw more skilled applicants

- Fostering loyalty: Well-paid workers develop stronger organizational commitment

In nutshell

The labor market represents a complex and dynamic system that lies at the heart of economic and social functioning. Its structure, participants, and mechanisms of equilibrium and adjustment continuously evolve in response to technological, demographic, and institutional changes.

Understanding the labor market requires both macroeconomic and microeconomic perspectives. Macroeconomic analysis reveals economy-wide patterns and relationships between labor markets and broader economic conditions. Microeconomic analysis illuminates the incentives and constraints facing individual workers and employers as they make decisions about participation, hiring, and compensation.

Contemporary labor markets face significant challenges, including technological disruption, demographic shifts, globalization, and changing worker preferences. Addressing these challenges requires thoughtful policy approaches that balance flexibility with security, efficiency with equity, and short-term adjustment with long-term resilience.

As we navigate the future of work, a comprehensive understanding of labor market dynamics will be essential for policymakers, business leaders, and individuals alike. By recognizing the multifaceted nature of labor markets and their central role in economic systems, we can work toward creating labor market institutions that promote both prosperity and inclusion in an evolving economic landscape.

References

- Autor, D. H. (2014). Skills, education, and the rise of earnings inequality among the "other 99 percent." Science, 344(6186), 843-851.

- Blanchard, O., & Katz, L. F. (2017). Movements in the supply and demand for labor. Handbook of Macroeconomics, 2, 1855-1874.

- Card, D., & Krueger, A. B. (2015). Myth and measurement: The new economics of the minimum wage. Princeton University Press.

- Doeringer, P. B., & Piore, M. J. (1971). Internal labor markets and manpower analysis. D.C. Heath and Company.

- Freeman, R. B., & Medoff, J. L. (1984). What do unions do? Basic Books.

- Krueger, A. B., & Ashenfelter, O. (2018). Theory and evidence on employer collusion in the franchise sector. IZA Discussion Paper No. 11672.

- Manning, A. (2003). Monopsony in motion: Imperfect competition in labor markets. Princeton University Press.

- OECD. (2023). Employment Outlook 2023: The Future of Work. OECD Publishing.

- Pissarides, C. A. (2000). Equilibrium unemployment theory. MIT Press.

- World Economic Forum. (2023). The Future of Jobs Report 2023. World Economic Forum.