Lean Supply Chain Management

- Details

- Category: Supply Chain Management

- Hits: 24,782

In today's competitive global marketplace, businesses are continually seeking ways to gain a competitive edge. One approach that has revolutionized how companies manage their supply chains is Lean Supply Chain Management. This methodology, built on the foundation of eliminating waste and focusing on customer value, has transformed industries worldwide. By streamlining processes, reducing inventory costs, and enhancing overall efficiency, Lean Supply Chain Management enables organizations to respond more effectively to customer demands while maximizing profitability.

As markets become increasingly volatile and customer expectations continue to rise, the principles of lean thinking have never been more relevant. This blog explores the core concepts of Lean Supply Chain Management, its historical origins, fundamental principles, and the essential tools used to implement this powerful approach.

What is Lean Supply Chain?

A Lean Supply Chain is an integrated set of processes designed to minimize waste while maximizing value to the end customer. Unlike traditional supply chain models that often focus on mass production and maintaining large inventories, lean supply chains emphasize flexibility, efficiency, and continuous improvement.

At its core, a lean supply chain seeks to eliminate the "seven wastes" identified in lean thinking:

- Transport: Unnecessary movement of materials or products

- Inventory: Excess stock that isn't immediately needed

- Motion: Unnecessary movement of people or equipment

- Waiting: Idle time between process steps

- Overproduction: Making more than is immediately needed

- Overprocessing: Additional steps that don't add value

- Defects: Errors requiring rework or scrapping

By addressing these wastes throughout the supply chain—from suppliers to manufacturing to distribution—organizations can create a streamlined system that delivers products and services exactly when and where they're needed, with minimal excess cost or delay.

A lean supply chain is characterized by:

- Just-in-time delivery of materials and products

- Pull-based systems driven by actual customer demand

- Close collaboration with suppliers

- Standardized work processes

- Visual management techniques

- Continuous improvement culture

These characteristics enable companies to maintain lower inventory levels, reduce lead times, and respond more quickly to changing market conditions—all while maintaining or improving quality standards.

Origins of the Lean Manufacturing

The concepts underlying Lean Supply Chain Management originated in manufacturing, specifically with the Toyota Production System (TPS) developed in Japan after World War II. Facing resource constraints and limited manufacturing space, Toyota engineers Taiichi Ohno and Shigeo Shingo developed a production system focused on eliminating waste (muda) and maximizing efficiency.

The term "lean" was popularized in the 1990s by researchers at MIT who studied Toyota's approach. In their influential book "The Machine That Changed the World," James Womack, Daniel Jones, and Daniel Roos introduced Western businesses to these principles, coining the term "lean manufacturing."

Key historical developments include:

- 1950s: Development of TPS principles at Toyota, including kanban (pull) systems

- 1970s: Oil crisis pushes Western manufacturers to explore Toyota's efficiency-focused methods

- 1980s: Growing interest in Japanese manufacturing techniques in North America

- 1990s: Publication of "The Machine That Changed the World" and widespread adoption of lean principles

- 2000s: Extension of lean thinking beyond manufacturing into services, healthcare, and supply chain management

What began as a manufacturing methodology has evolved into a comprehensive business philosophy that can be applied across industries and functions, including supply chain management.

Lean manufacturing emphasises the optimisation across organisations and supply bases not just the functional silos. It promotes close partnership relations with the first tier suppliers and other strategic partners in the distribution channel. It created the tiered supply base structure. The waste between the organisations, often ignored in the past, has been identified as key improvement area. The modular design of the automobile has been master minded to fit to the tiered supply structure. All in all, the lean system has also transformed the supply chain management which we call the lean supply management. This is precisely I am going to discuss in this chapter.

Lean Supply Principles

Lean Supply Chain Management operates on five core principles:

1. Specify Value from the Customer's Perspective

All supply chain activities should be evaluated based on whether they contribute to what customers truly value. This requires understanding what customers are willing to pay for and eliminating processes that don't contribute to that value.

2. Identify the Value Stream

The entire sequence of activities required to bring a product from raw materials to the customer must be mapped and analyzed. This includes information flows as well as physical flows, identifying steps that create value and those that represent waste.

3. Create Flow

Once waste has been identified, the remaining value-creating steps should flow smoothly without interruptions, delays, or bottlenecks. This often involves reconfiguring traditional batch-and-queue processes into continuous flow operations.

4. Establish Pull

A pull-based system ensures that nothing is produced until it's needed by the downstream customer. This contrasts with traditional push systems that produce according to forecasts, often leading to overproduction and excess inventory.

5. Pursue Perfection

Lean implementation is not a one-time event but a journey of continuous improvement. Organizations must constantly seek to eliminate newly revealed wastes and improve processes as they evolve.

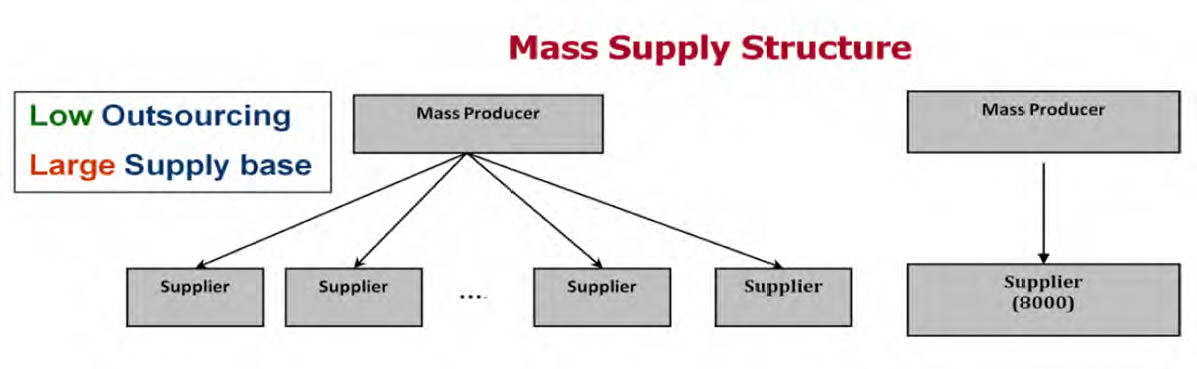

To understand what’s unique about lean supply and how it works, one must first examine the supply chain practice in mass production, knowing the whole lean manufacturing system was originally evolved from inherited mass production system. In the mass production supply system, the mass producer buys its basic components from a large supply base.

The supplier number will normally reach 5000 to 8000, bearing in mind that a modern automobile will have more than 20,000 basic components built into it. As shown in Figure 14 the mass supply structure is very flat. The mass producer takes on the assembly of the whole vehicle as well as many subsystems and modules. Thus the level of outsourcing is relatively low.

Figure 14. Mass supply chain structure.

The mass producer will design the parts to be made by the suppliers. The process is basically a sequence of one-step-a-time from design, bid, prototype, check, contract and make. With this system, when it comes to find and select the supplier, the cost will always come first. Whosever can make the same part at a lower price will win the bid. This will often lead to a scenario that the suppliers will quote a low price to win the bid and then expecting to raise the price through the annual price adjustment. Suppliers will hardly share any information with the buyer other than the volume and price.

The consequence of the mass supply system is far from beneficial. Supplier brought into the production too late that even the suppliers have better ideas on the design; it would be too late to change. Perhaps the buyer never intended to make use of the suppliers’ know-how on the design of the vehicle anyway. Intense cost pressure from the buyer to suppliers are detrimental that the buyer often play-off the suppliers making them reluctant to share production information.

This also made it impossible for the buyer to estimate the true cost of making the parts. When the supplier has improved its production efficiency there is no incentive to merge the learning curve (to share the saving). All these resulted in high parts cost and unsatisfactory quality.

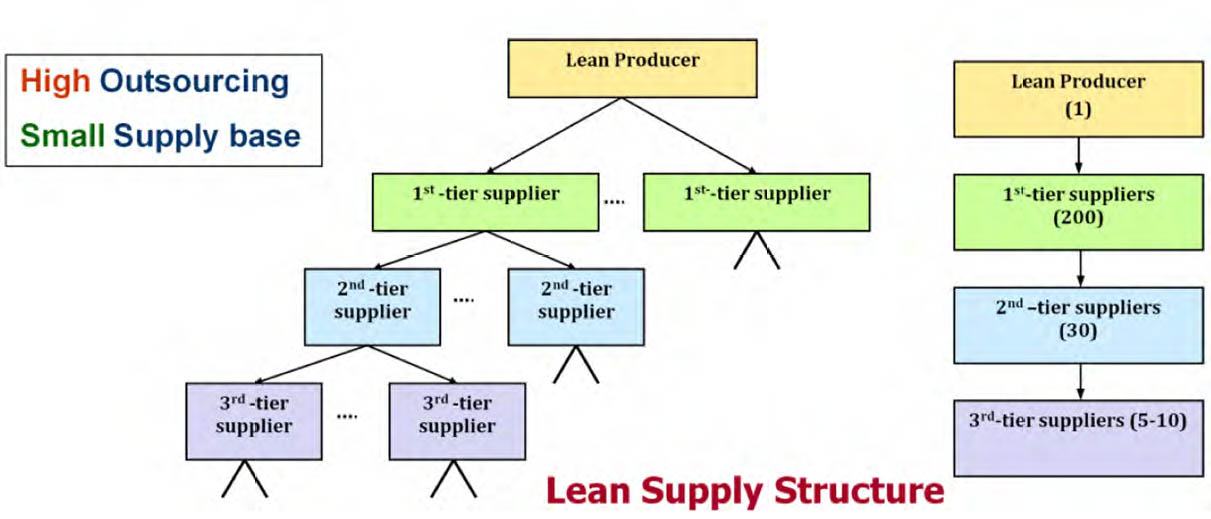

Over the years the Japanese developed a set of completely different practices - the lean supply system (Figure 15). They can be summarised in 10 lean supply principles that are in stark contrast with what the mass supply system was about.

Figure 15. Lean supply chain structure.

Lean Supply Chain Management: key characteristics

Smaller first-tier supply base

Lean producers utilize a tiered supplier structure with only 200-300 first-tier suppliers, significantly fewer than traditional mass production systems. These first-tier suppliers directly provide all subsystems, modules, and components, forming the "supply base." This structural change drives numerous supply chain behavior changes that deliver competitive advantages.

Close partnerships with suppliers

With a smaller supply base, lean producers can dedicate more time and resources to each first-tier supplier, enabling closer operational relationships. These partnerships typically involve:

- Shared vision and mission

- Joint design and development of new products

- Strategic collaboration on capital investment planning

- Synchronized capacity planning

- Coordination on just-in-time delivery and inventory optimization

- Medium to long-term contracts

- Multi-level communication and engagement (both formal and informal)

Performance-Based supplier selection

Unlike mass producers who prioritize price, lean producers select suppliers based on multiple performance criteria:

- Quality standards

- R&D capabilities

- Delivery reliability

- Management systems and standards

- Commitment and relationship quality

Price remains a consideration but is always referenced against the value the supplier can offer. Once selected, suppliers are treated as "family members" within an open and trusting culture.

Single or dual sourcing strategy

Lean producers prefer "single sourcing" or "dual sourcing" rather than "multiple sourcing." Single sourcing means obtaining a unique product (with unique SKU) from only one supplier. This approach offers several advantages:

- Consolidates volume to minimize unit costs (economy of scale)

- Simplifies research and product development

- Demonstrates trust and partnership commitment

However, this strategy does involve certain risks, including potential supply disruptions and the possibility of supplier complacency due to lack of competition.

"Market Price Minus" pricing approach

Lean supply chains handle pricing differently than traditional "supplier cost-plus" models. Instead of accepting the supplier's cost model and adding a profit margin, lean producers:

- Determine the market price through research and benchmarking

- Subtract an agreed reasonable profit margin for the supplier

- Establish the remaining amount as the "target cost"

If the supplier's actual cost exceeds the target cost, both parties work together to reduce costs. This approach ensures market-acceptable pricing throughout the supply chain while securing appropriate profit margins for suppliers.

Early supplier involvement in new product introduction

Unlike mass production systems where suppliers simply manufacture according to provided blueprints, lean systems:

- Identify suppliers first

- Involve them in the design and planning stages of new product introduction

This collaborative approach allows suppliers to contribute their expertise, generate innovations, and eliminate potential production issues at the earliest design stage. Supplier engineers may even work on-site as "residential engineers," promoting supply chain collaboration and integration.

Synchronized flexible capacity

Rather than maintaining fixed capacity, lean supply systems build synchronized flexible capacity throughout the supply chain. This flexibility means:

- Rapidly increasing or decreasing production levels

- Quickly shifting production capacity between products or services

This adaptability is achieved through flexible plants, processes, workers, and strategies that leverage the capacity of other organizations, preventing both over-capacity during low demand and under-capacity during high demand.

Just-in-Time delivery

Just-in-Time (JIT) is a fundamental lean philosophy where processes operate only when customers signal a need for more parts. In lean supply chains:

- Goods are produced and delivered just-in-time to be sold

- Parts are produced and delivered just-in-time for assembly

- Work begins in response to customer demand

- The entire supply network functions as a chain of customers

- End-consumer demand triggers the entire system

- Materials and goods flow through a "pull system"

Incentive and reward alignment

Lean supply chains emphasize alignment with suppliers through incentives and rewards. The objective is collaboration to reduce costs rather than extracting profit from suppliers. Typical practices include:

- Allowing suppliers to retain 50% of efficiency-related cost savings

- Rewarding design improvements and quality contributions with additional business

- Aligning value creation with rewards

- Boosting supplier motivation and commitment

Information sharing and transparency

Lean supply chains foster a culture of mutual trust and loyalty. Suppliers willingly share substantial proprietary information with buyers, creating:

- Improved supply chain visibility

- Easier coordination

- Synergy between parties

- Increased value of information through wider utilization

Optimizing cost-to-serve in Lean Supply Chain Management

A critical aspect of Lean Supply Chain Management is understanding and optimizing the "cost-to-serve" different customers and market segments. This approach recognizes that not all customers have the same service requirements or contribute equally to profitability.

Cost-to-serve analysis involves:

- Segmenting customers based on their value and service requirements

- Analyzing the true costs of serving different customer segments

- Developing tailored supply chain strategies for each segment

- Eliminating unprofitable activities that don't align with customer value

Understanding cost-to-serve

A fundamental element of Lean Supply Chain Management is the analysis and optimization of "cost-to-serve" across different customer segments. This concept recognizes that customers have varying service requirements and contribute differently to overall profitability.

Effective cost-to-serve analysis requires:

- Customer segmentation based on value and service needs

- Detailed assessment of the true costs associated with each segment

- Development of customized supply chain strategies per segment

- Elimination of activities that don't contribute to customer value

By deeply understanding the relationship between service levels and costs, organizations can make strategic decisions about resource allocation and supply chain structure. This might include offering premium delivery options to high-value customers while implementing standard delivery schedules for others who don't require enhanced service.

Beyond simple cost cutting

Viewing lean supply chain management as merely a cost-cutting exercise fundamentally misses the point. Such a misinterpretation transforms a "lean" supply chain into a "mean" supply chain. While cost efficiency is certainly a priority in creating leaner processes, the subtle yet critical distinction between low-cost and lean approaches cannot be overlooked.

In a genuinely lean supply chain, cost reduction initiatives must pass the "cost-to-serve" test to be considered viable. The focus shifts from arbitrary cost cutting to optimizing the cost-to-serve ratio.

The essence of lean thinking

Since Toyota demonstrated exceptional leadership in production management, organizations have been applying lean principles to logistics systems and broader supply chain management. However, misconceptions about the original concepts often lead to unrealistic expectations regarding benefits.

The core of lean methodology involves identifying and eliminating waste in materials, processes, time, and information flows, while enhancing value from the customer's perspective. The primary target is waste elimination across the management spectrum—not necessarily cost reduction for its own sake. When a cost is identified as waste that adds no value, it should be eliminated. The key challenge is identifying which costs add no value.

Defining value-adding activities

Toyota established three fundamental criteria for value-adding activities:

- They must create physical changes

- They must be valued by the customer

- They must be performed correctly the first time

Activities failing to meet these criteria are considered wasteful and non-value-adding. This is where the concept of "serve" becomes relevant. If an activity adds value that customers perceive, it "serves" them effectively. Therefore, lean principles should focus on identifying and eliminating non-value-adding or non-serving activities.

Measuring cost-to-serve

A practical formula for measuring cost-to-serve is:

Cost-to-serve = Total cost involved / Customer perceived value and service

This metric allows comparison between activities to determine which adds more value and which constitutes waste. When total costs remain constant, increased customer-perceived value and service reduce the cost-to-serve ratio, indicating greater efficiency.

The lean approach isn't about indiscriminate cost cutting but rather about reducing the cost-to-serve ratio. The ultimate goal is to minimize this ratio throughout the supply chain.

Practical applications

This cost-to-serve concept explains why some organizations achieve low costs by ensuring customers aren't over-serviced, while others create leaner supply chains by strategically investing more in operations that enhance customer value. Both approaches can be valid within the lean framework, provided they optimize the relationship between costs and customer-perceived value.

Key drivers of a lean supply chain

Organizations are increasingly adopting lean supply chains due to several key factors:

1. Global competition

As markets expand, companies face intense competition, driving the need for greater efficiency and lower costs.

2. Customer expectations

Consumers demand faster delivery, flawless quality, and competitive pricing, pushing businesses to reduce waste and enhance responsiveness.

3. Technological advancements

IoT, analytics, and automation provide better supply chain visibility and control, making lean practices more achievable.

4. Economic [ressures

Uncertain economies and shrinking margins force organizations to maximize efficiency by eliminating waste.

5. Sustainability

Lean principles align with environmental goals by reducing resource consumption and waste.

Core elements of a lean supply chain

1. Waste reduction

Eliminating waste is a fundamental lean principle. Waste in supply chains includes excess time, inventory, redundant processes, and defects. Collaboration among supply chain partners is critical to removing inefficiencies.

While cost reduction is a byproduct of waste elimination, focusing solely on cutting costs can be misleading. A company shifting inventory responsibility to a supplier may reduce its own costs, but the total supply chain cost remains unchanged. True waste reduction requires a holistic supply chain perspective.

Often, waste lies in gaps between suppliers and buyers, such as failing to involve suppliers early in product development. To address this, companies should adopt joint waste-reduction strategies through cross-functional teams and collaborative policies.

2. Demand management

Effective demand management is key to supply chain success. Meeting consumer demand efficiently depends on real-time data sharing, forecasting, and market insights.

Advanced point-of-sale (POS) systems and resource planning tools enhance demand visibility. However, collaboration between suppliers and buyers is equally important. Organizations must integrate demand management into their culture, fostering communication, commitment, and structured meetings with supply chain partners.

3. Process standardization

Standardizing processes across the supply chain enables smooth, uninterrupted product and service flow. Bottlenecks—such as work queues, batch processing, and inefficient transportation—slow operations and increase costs.

Shifting from vertical organizational silos to horizontal, value-stream-focused processes improves efficiency. Standardized production planning, materials, and components help reduce complexity, drive consistency, and optimize costs.

4. Engaging people

Lean supply chains thrive on employee involvement. Lean is not just a leadership initiative—it requires commitment from all levels, especially frontline workers.

When employees are actively engaged, organizations unlock their knowledge and expertise. This enhances motivation, strengthens operational improvements, and fosters a culture of continuous improvement. A lean supply chain is sustainable only when built into the company’s culture.

5. Collaboration

Lean supply chains rely on collaboration—both within and across organizations. Shared resources increase efficiency, reduce risk, and drive innovation.

Collaboration can be top-down, where executives set strategic partnerships, or bottom-up, evolving from operational teamwork. Either way, successful collaboration requires clear intentions, structured agreements, and well-defined processes.

6. Continuous improvement

Lean thinking emphasizes ongoing improvement—progress happens incrementally over time. The Toyota Production System, for example, evolved through years of continuous refinements.

A structured continuous improvement process (Kaizen) encourages employees to make small, ongoing enhancements. Key Kaizen principles include:

- Small, incremental changes over time rather than major overhauls

- Employee-driven improvement ideas

- Minimal need for capital investment

- Encouraging employees to take ownership of performance

By embedding a culture of continuous improvement, organizations ensure sustained lean supply chain success.

Lean process mapping tools

Several tools help organizations identify and eliminate waste in their supply chains:

Value stream mapping (VSM)

A visual tool that documents, analyzes, and improves the flow of information or materials required to produce a product or service. VSM helps identify value-adding and non-value-adding activities across the entire supply chain.

Process activity mapping

A detailed analysis of each step in a process, categorizing activities as value-adding, non-value-adding but necessary, or pure waste.

Supply chain response matrix

A time-based diagram that shows lead times and inventory at each stage in the supply chain, highlighting opportunities to reduce delays and excess stock.

Production variety funnel

A visual tool that analyzes the point at which products assume their unique characteristics, helping to optimize product variety without creating complexity.

Quality filter mapping

A tool that identifies where quality defects occur in the supply chain, enabling targeted improvement efforts.

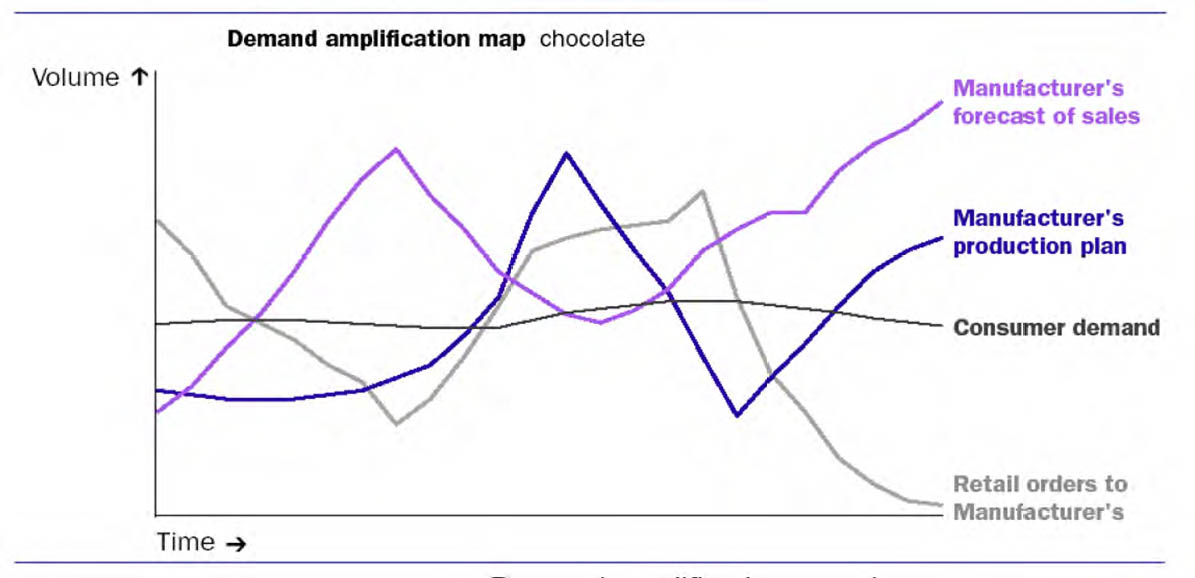

Demand amplification mapping

Also known as the "bullwhip effect" analysis, this tool illustrates how demand variations are amplified as they move upstream in the supply chain.

Decision point analysis

Identifies the point in the supply chain where production switches from make-to-stock to make-to-order, helping optimize inventory positioning.

These mapping tools provide visibility into existing processes, making waste visible and creating a foundation for improvement efforts. They help organizations see beyond individual functions to understand how the entire supply chain operates as a system.

Lean approach, unlike many other ‘flavour of the month’, has been extremely enduring. After three decades of worldwide preaching and application, lean movement is still going strong. In today’s business management world, lean method is still the most popular one across the world. Over more than 70% of organisations have, to various extents, exercised lean. One of the reasons why lean is so widely applied and continues to be the most favourable method is that it has a set of practical tools that can be readily applied in almost all business circumstances.

The tools created originally by the Toyota production systems are called ‘lean process mapping tools’. The purposes of those tools are to visualise the material flows in the production lines and in the supply chains; to see where the waste is. They help to pull together the lean thinking principles and facilitate the discussion and communication, and help to identify the bottleneck and prioritise the remedial actions. There are quite many widely used tools that can directly support lean supply chain management.

Most of the figures of the tools are sourced from the article ‘Going lean’ by Peter Hines and David Taylor (2000).

- Value Stream Mapping

- Time Based Process Mapping

- Process activities mapping

- Supply chain response matrix

- Logistics pipeline map

- Production variety funnel

- Quality filter mapping

- Demand amplification mapping

- Value adding time profile

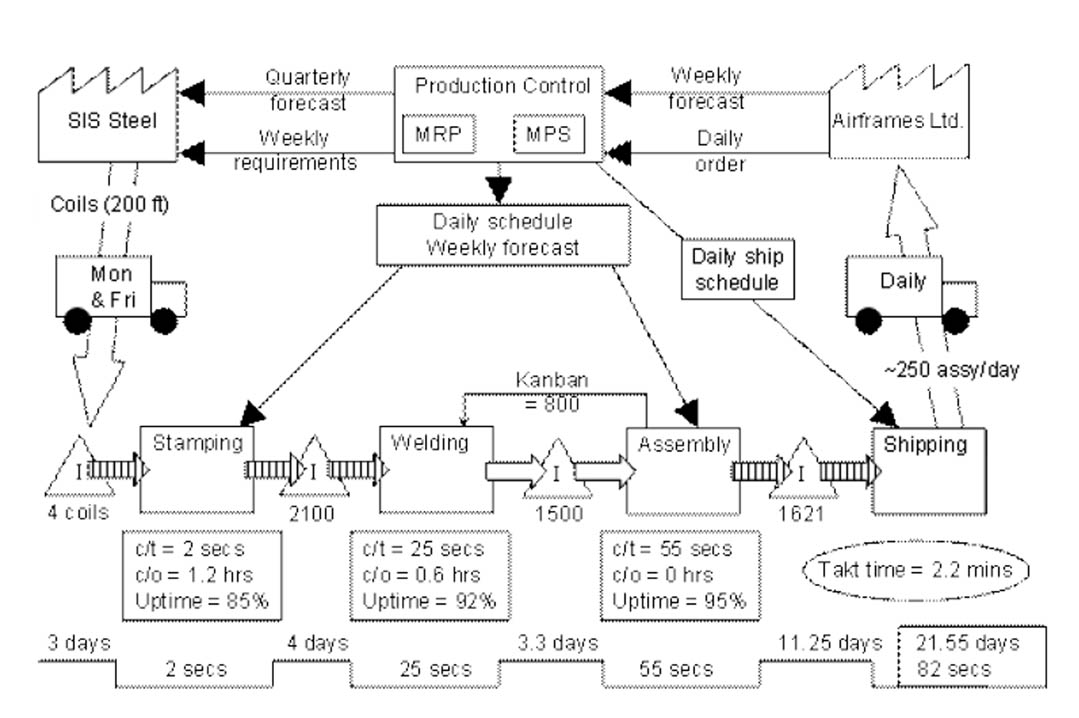

The value stream mapping tool as shown in figure 16 is designed to map out the value adding and wastage from the supplier to customer, including logistics, purchasing, order fulfilment, production processes.

Figure 16. Value stream mapping tool

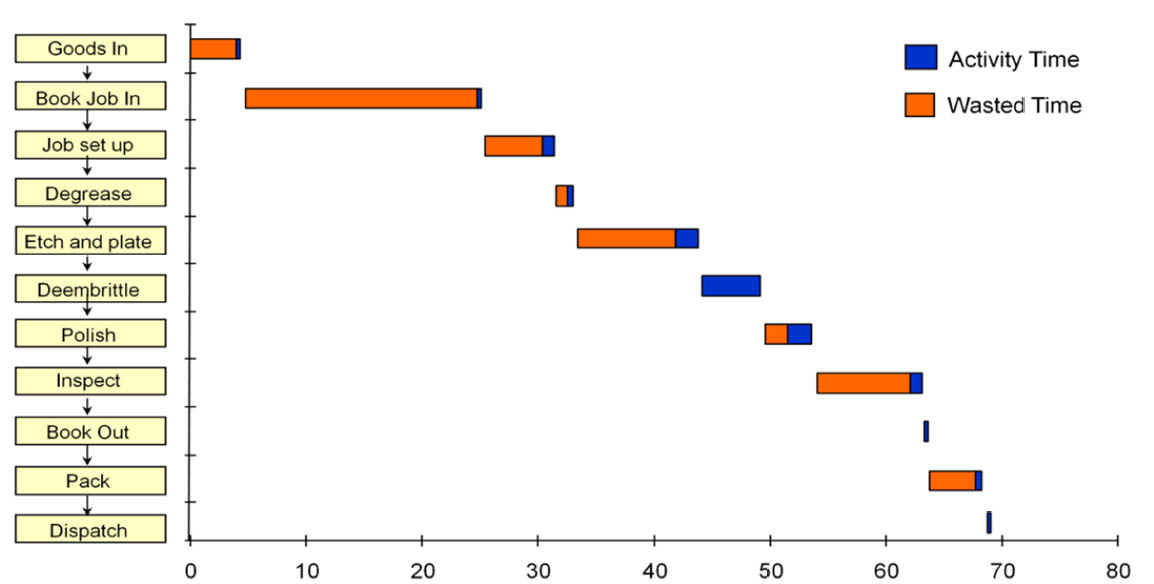

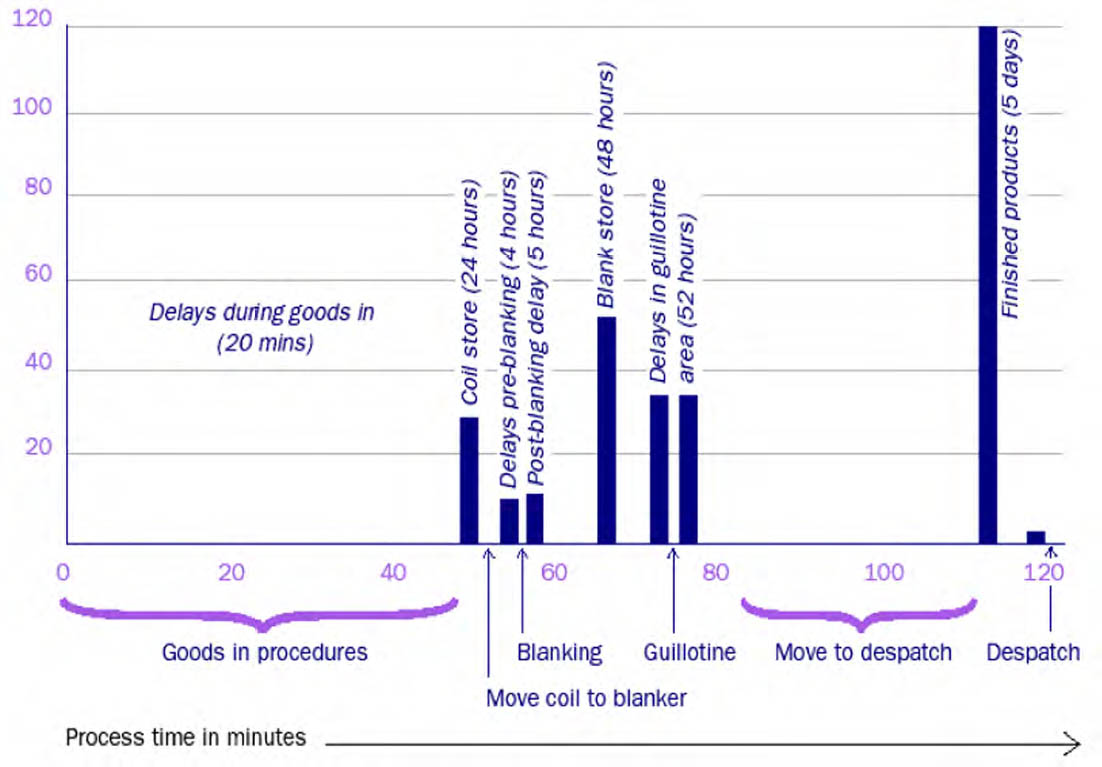

The time-based process mapping tool is a simply ‘walk through’ tool to identify and map out the activity time (suppose to be value adding) and waste time (non-value adding) in every steps that the material has gone through, as shown in Figure 17.

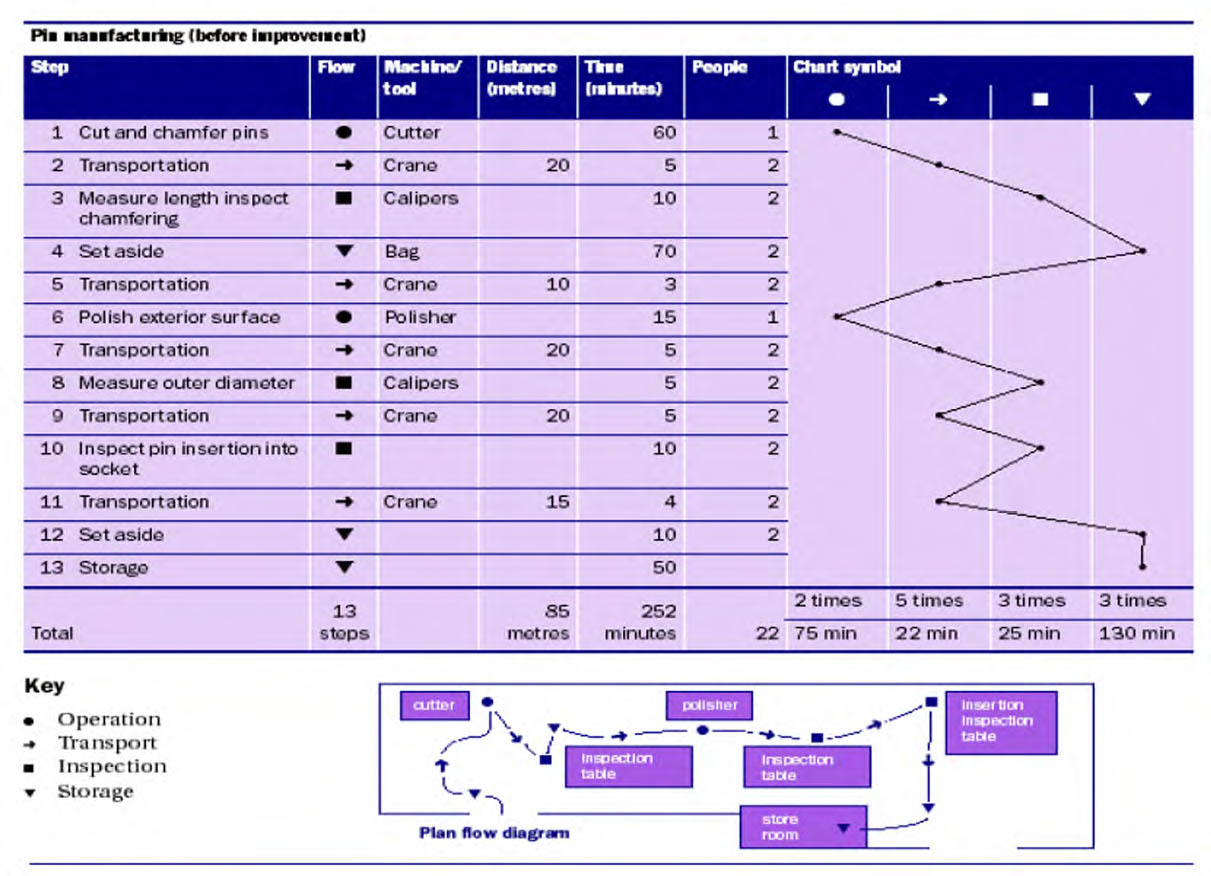

The process activity mapping tool maps out the four different activities: operation, transport, inspection and storage that the materials have to go through. Keys are assigned to each activity types to help visualisation. Plan flow diagram can also be added to optimise the flow.

Figure 17. Time-based process mapping

Figure 18. Process activity mapping

The supply chain response matrix is used to evaluate the inventory and lead times incurred by a supply chain in maintaining a given level of customer service. It is used to identify large sects of time and inventory and allows managers to assess the need to hold the inventory.

Figure 19. Supply chain response matrix.

The logistics pipeline map is a compliment to the supply chain response matrix. It shows the accumulation of process time on the horizontal axis and of inventory levels on the vertical axis. It shows exactly where the inventory and time accumulate within each operation (see figure 20).

Figure 20. logistics pipeline map

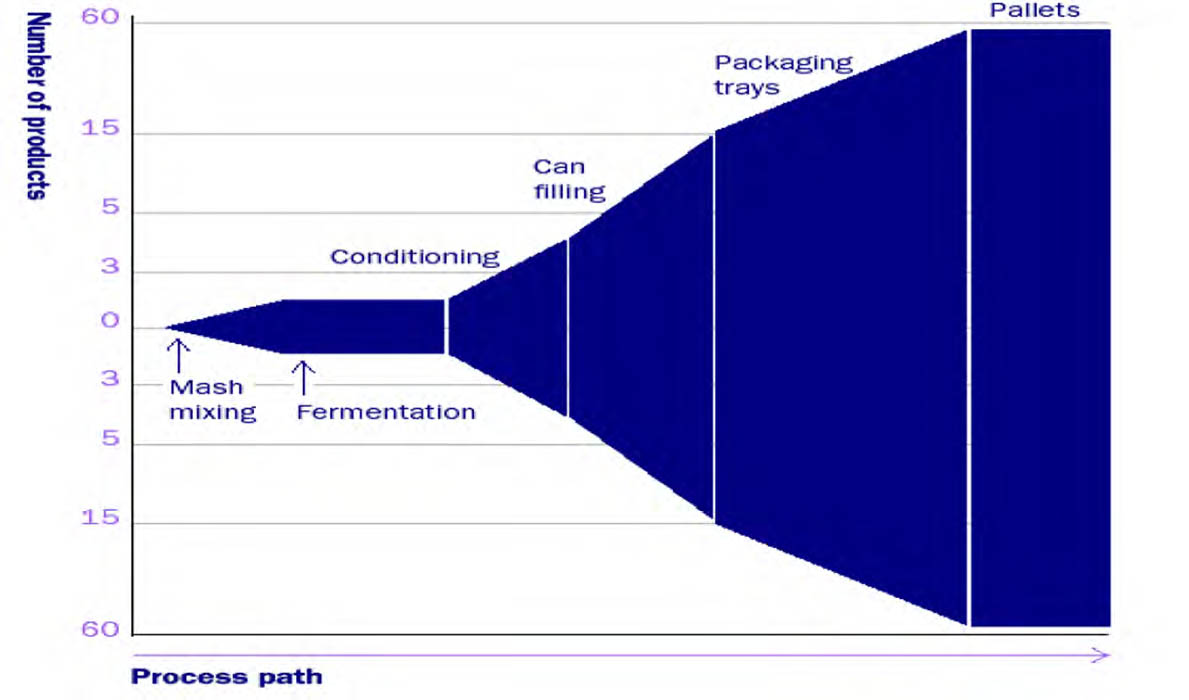

Production variety funnel is a visual mapping technique that plots the number of product variety at each stage of the manufacturing process. This technique is used to identify the point at which a generic product becomes either increasingly or totally customer specific.

Figure 21. Product variety funnel.

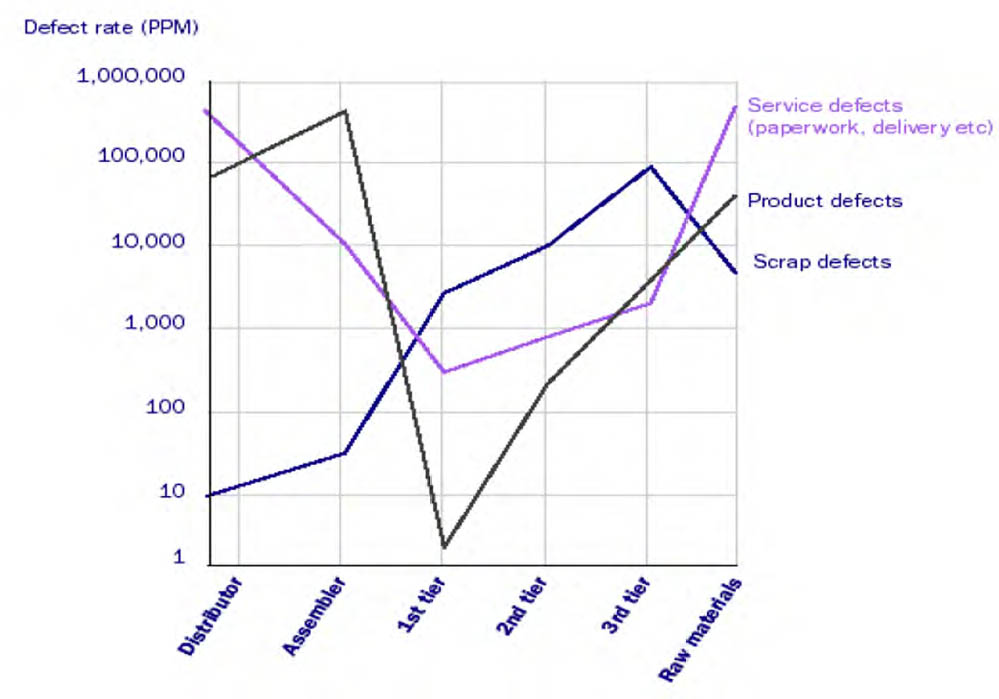

Quality filter mapping is a tool designed to identify quality problems in the order fulfillment process or the wider supply chain. The map shows where three different types of quality defects occur in the value stream.

Figure 22. Quality filter mapping.

Demand amplification mapping is a graph of quantity against time, showing the batch sizes of a product at various stages of the production process. This may be plotted with a company or along the supply chain. It also can be used to show inventory holdings at various stages long the supply chain.

Figure 23. Demand amplification mapping.

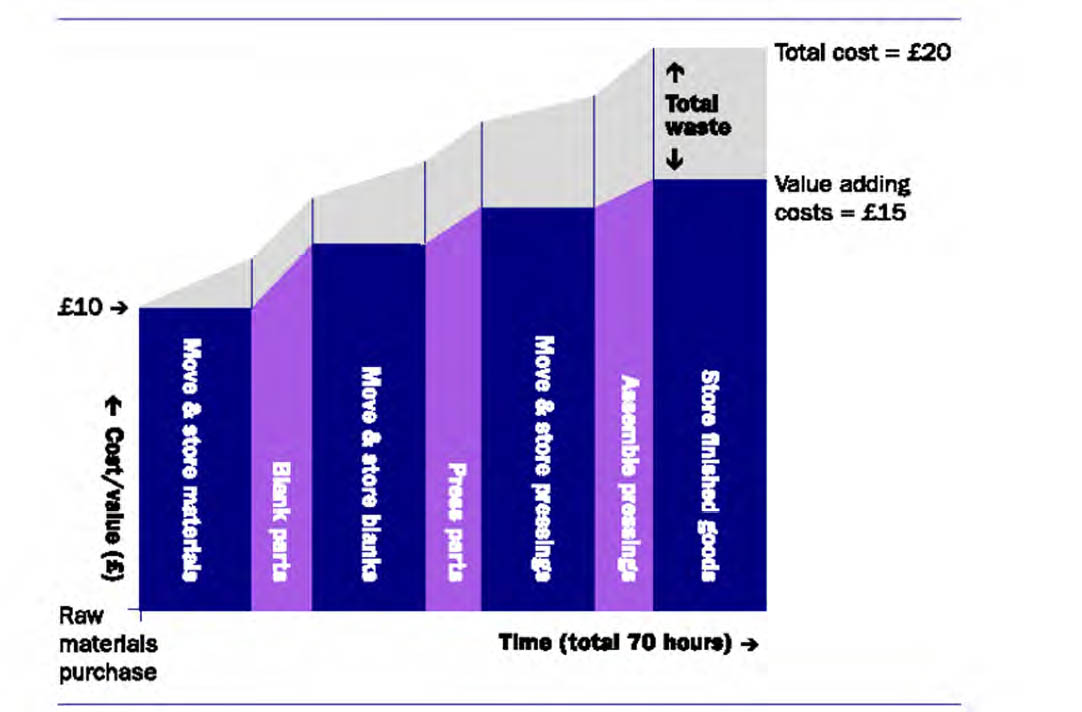

Value-adding time profile plots the accumulation of both value-adding and non-value adding costs against the time. It is an excellent tool for looking at time compression or mapping out where the money is being wasted.

Figure 24. Value-adding time profile.

Lean Supply Chain Management represents a powerful approach for organizations seeking to enhance competitiveness in today's challenging business environment. By focusing relentlessly on customer value, eliminating waste, and pursuing continuous improvement, companies can build supply chains that are not only more efficient but also more responsive to evolving market demands. The journey toward a lean supply chain is ongoing, but the rewards—reduced costs, improved quality, faster delivery, and increased customer satisfaction—make it well worth the effort.