The Future Challenges supply chain management

- Details

- Category: Supply Chain Management

- Hits: 15,159

What’s the future holds for supply chain management? The future of supply chain management is the future of business management when there will be no business that is not part of a supply chain. The paradigm of business management will soon be converged to the paradigm of supply chain management. To precisely fortune-tell the future of supply chains is meaningless.

But what’s useful is to identify and explore some challenges that we better prepare ourselves for. Three key challenges have been identified and discussed here.

Creating Customer-Centric Supply Chain

The first challenge that the supply chain managers are facing is to transform the supply chains from supplier-centric to customer-centric. Traditionally, supply chains have been developed from factory outwards so that the company’s business model may be continued without major change. The management emphasis was on how to ensure the production process could be most efficiently run and products could be most cost-effectively distributed. The marketing is to find the customer that fits the products rather than to make the products that fit the market.

In today’s highly competitive global market place, the market favors whichever the supply chain that satisfies them best. The strategic aim of the supply chains must be on the higher levels of customer responsiveness. Thus the agility rather than the cost becomes the key diver. The supply chains must be designed to get the customer on the driving seat. Coordination and operational integration of the supply chain members must be significantly strengthened to counterbalance the increased volatility of market behavior.

It is anticipated that there will be a culture change towards the 21st Century supply chain management. This change, which is already underway, is expected to transform the business model from supplier centric to customer-centric. The customer-centricity idea represents a renewed paradigm that will have profound implications through every aspect of supply chain management. Research shows that close connectivity to the customer will significantly improve supply chain effectiveness and market performance.

Traditionally, this task of customer connection is left to only small part of the supply chain. Dealers and service/repair shops have most information about the consumer, with OEMs and suppliers having the least. However, in the future’s supply chain, more information is shared across the network. With online communities, embedded systems connected online configuration and ordering the future supply chain will have more information about consumers than ever before.

More importantly, it will have better intelligent analytics to synthesize and use the information. Across industries, demand planning with customers in the center will become a standard process for synchronizing supply and demand. Customer centricity also will play a pivotal role in customer collaboration on product innovation. Already more and more supply chains support customer product configuration and specification and collaborate extensively with customers on product design.

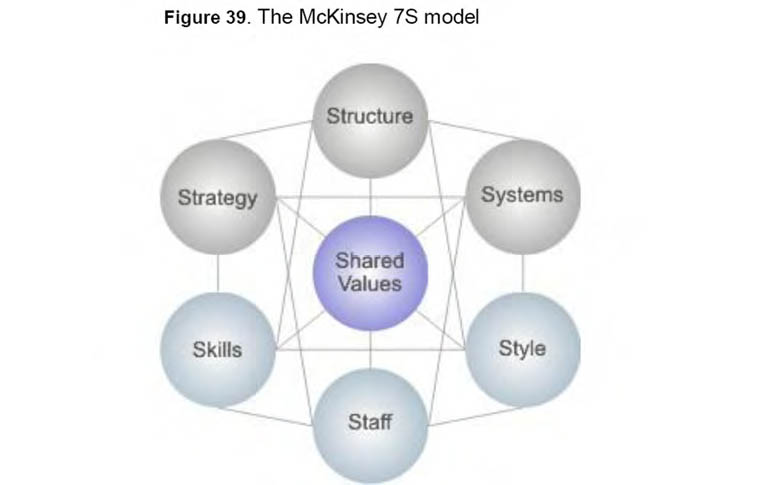

While many models of organizational effectiveness can be used for transforming the organization, one that has persisted is the McKinsey 7S framework. Developed in the early 1980s by Tom Peters and Robert Waterman, two consultants working at the McKinsey & Company consulting firm, the basic premise of the model is that there are seven internal aspects of an organization that need to be aligned if it is to be successful.

Three of those are what they call the “Hard” elements and four are “Soft” ones. The “hard” elements are easier to define or identify. The management can directly influence them. These are strategy statements; organization charts and reporting lines; and formal processes and IT systems. The “soft” elements, on the other hand, can be more difficult to describe, and are less tangible and more influenced by culture. However, these soft elements are as important as the hard elements if the organization is going to be successful.

Figure 39: The McKinsey 7S Model

Let’s look at each of the elements specifically to see how a customer-centric supply chain can be achieved:

- Strategy: from the top of the organization a customer-oriented strategy must be drawn and put to be communicated throughout the organization. The strategy must include how the organization should align its strategy with the suppliers and customers to have the visibility and responsiveness to the end-consumers’ demand.

- Structure: For the organization, horizontal dynamic structure that aligned to products and market segment is more preferred that the vertical hierarchical reporting lines; for the supply chain, networked flexible structure with a small span of vertical integration is more responsive to the customer demand.

- Systems: the procedures and daily activities must be in tune with market sentiment; customer complaints and requests must be dealt with by a fixed routine procedure systematically; a joint forecasting and new product introduction process should be established collaboratively across the supply chain.

- Shared value: customer service and customer value must be enshrined in the core organizational value; it should become the culture and second nature for people to act on anything related to the customer and end- consumer at the highest priority.

- Style: the leadership style adopted must fit the culture of customer orientation and customer-centric.

The leaders and management team should ‘walk the talk’ and become the role model in caring about the customer.

- Staff: the employee and their capabilities are the assets of the organization. People are the only active force in caring and serving the customer. The change of organizational performance is almost entirely dependent on the changes of people’s understanding, knowledge and attitude.

- Skills: the quality of the products, the level of customer satisfaction, rely on the skills of the workforce, which in turn determines the organization’s and supply chain’s competences in delivering the products and services.

Managing Supply Networks

The second challenge is to take on the whole supply network and manage it as an integrated entity. Managers see the only legitimate platform for them to exercise control is their own organization, beyond which is the supply chain they participated. This limited scope of business management is to be and has already been challenged. Companies will not stand alone in the competition. Like it or not the competition will only be waged with supply chain against the supply chain. The survival of the supply chain is the survival of the organizations in it.

Therefore the new competitive paradigm place the firm in the middle of an interdependent network - a confederation of mutually complementary competencies and capabilities - which competes as an integrated supply chain against other supply chains. To manage in such a radically revised competitive structure clearly requires different skills and competencies than those used in the traditional structure. To achieve future global market leadership in the networked competitive environment necessitates a network focused management model and the associated management processes.

One of the key cognitive characteristics of any network is its configurative structure, which specifies how a supply chain is constructed in terms of its flow model. Such network structure dimension determines how big the supply base is; how wide the extent of vertical integration is; how much its level of outsourcing is; where the suppliers are located; how close the dyadic relationships are; what the channels of connection for the network are; and etc..

As it happens, globalization has, amongst many other forces, propelled some unprecedented shifts in network structure and configuration. Evidence from numerous surveys and case studies shows that more and more leading-edge enterprises are outsourcing more strategically important functions and vertically disintegrating the supply chain to geographically, economically and culturally remote destinations.

Such momentum has inevitably given rise to some new challenges in reshaping the network management. Business strategies formulation must be carried out collectively with the network members. A significantly higher level of joint strategic development is required in order for the network to be truly effective. Another challenge is for the networks to break free from the often adversarial nature of buyer-supplier relationships. There is now a growing realization that co-operation between network partners usually leads to improved performance generally. The result of the improved performance needs to be shared between the members of the network to achieve what’s called ‘win-win’.

Developing a shared information system for network management is another challenge. Forecasting information, capacity information, and production information can all be collectively managed to reduce the inventory levels and achieve shorter lead-time and JIT delivery. Throughout the supply, the material flows are gradual to be displaced by the information flow. Whilst the supply network becomes leaner in terms of less redundant materials in the process, the investment in the information systems and its management gets increasingly higher. Coordinating the IT system compatibility, software upgrading, maintenance and service could be resource hungry. However, the gain in the much more coordinated operation and supply chain responsiveness is understood to be worth the cost.

As supply network complexity and uncertainty become ever more persistent the challenges also ripple out to the supply chain risk management. This is particularly true when supply chains become more reliant on virtual networks. The emerging future model of risk management for supply chains cannot be a scheme of buying an insurance policy; nor would it be an experience of gambling. Companies that aspire for the supply chain leadership position in the future will be those who mitigate the risk by building various forms of reserves, including inventory, capacity, redundant suppliers, but in the meantime maintaining a competitive strength in business efficiency and responsiveness.

Managers thus must keep a vigilant eye on the trade-off between the risk and the cost of building a reserve to mitigate it. With so many related risks and risk-mitigation approaches to consider, it is suggested that managers must do two things when they begin to construct a supply network risk management strategy. First, they must create a shared organisationwide understanding of supply-chain risk. Then they must determine how to adapt general risk-mitigation approaches to the circumstances of their particular company.

Watch the Dynamics

The third challenge is how to survive the dynamics of the never-ending supply chain evolution. The future of the supply chain will face unprecedented dynamics in terms of structural dynamics, technological dynamics, and relationship dynamics, to say the least.

Structural dynamics

From a system dynamics point of view, the flow structure of a supply chain is a typical dynamic system with lows and stock; there are feedbacks and delays. From a managerial experience perspective, it is even more so; there are fluctuations of demand, overproduction, high inventory, capacity miss-match, backlogs of unfulfilled orders, delayed delivery and so on. The trouble is that the supply structure is growingly more complex, and market volatility is set to increase too. There is little doubt the dynamic behavior of a supply chain is only to be exacerbated.

A number of factors are at play, which is continuously contributing to the increased structural dynamics.

- The first factor is that business around the world is becoming more specialized, and they become so rightly for their competitive advantages, utilization of resources and returns on investment. This trend is leading to more inter-connections of the specialized operation in the supply chain networks. Specialization gives rise to the need for coordination in between. Thus increase the complexity of the system and more triggers for dynamic changes.

- The geographical expansion of supply chains around the world also exacerbates the dynamic behavior, as the delays in logistics and visibilities are worsened. It has also brought in the unstable factors such as different legal and financial systems, cultural and religious conflicts, indigenous market related ethical issues.

- The rapid growing environmental concerns around the world have already started to reshape the supply chains. Not only the resourcing strategies but also the production and logistics processes have felt a significant impact. The carbon footprint has become the KPI for many supply chains across industries, which they never heard of just a few years back. Consequently, the structure of the supply chains will have to change.

Technological dynamics

Innovation and technology advancement has been great news for the business and the consumers alike in most cases. But the changeover to new technologies can be a very painful process as it induces a series of dynamic changes to the supply chains. All too often the disruptive technology advancement decreases the existing operating model and invalidates the existing markets.

The changing dynamics that have been enforced upon the supply chain can be observed from the number of directions:

- The sudden change of competition landscape when the new technological advancement has helped the competitors to update their offerings to the market.

- The manufacturer may be forced to switch suppliers due to the desperate need for the new technology in the supply base in order to keep competitive.

- The sudden rise of the new investment requirement due to the pressure to upgrade the equipment and facilities to cater to the new technology.

- Unfolding a significant skill gap in the workforce due to the unpreparedness of the technology.

Relationship dynamics

Many people believe the operating core of supply chain management is that of relationships with the suppliers and buyers including the end consumers. Hence, the external business relationship management for a company has become the centerpiece of today’s and arguably the future’s supply chain management. However, the conceptual alignment of this concept in the academic as well as the practitioners’ circles has always been a quagmire, as there are many apparently conflicting approaches towards managing the relationships.

It is now emerging, that no single existing relationship model so far can possibly serve all business needs because of the underlying dynamism. There is basically two key dynamism in relationship management, one is the portfolio dynamism and the other is longitudinal dynamism. The portfolio dynamism addresses a portfolio of different relationship approaches that fit a corresponding portfolio of business models.

Thus, in oftentimes, the business will need to harness with a number of different supply chain relationships to different suppliers based on product categories, market segmentation, development strategies, and financial circumstances and so on. The longitudinal dynamism addresses the changing relationship posture along the time continuum. In this way, the relationship management becomes a powerful instrument to achieve the supply chain responsiveness and supply chain agility. It is anticipated that the future supply relationship management will hinge on a combined approach that addresses both the portfolio and longitudinal dynamisms.

How to survive the supply chain dynamics?

The Triple-A supply chain model proposed by Professor Hau Lee (2007) from Stanford University is a useful blueprint to survive the supply chain dynamics.

The triple-A stands for Agility, Adaptability and Alignment. A supply chain must be agile enough in order to respond quickly to the dynamics of demand fluctuations and sudden changes of supply. The agility is a supply chain capability that handles the unexpected external disruptions smoothly and cost-effectively. It enables the supply chain to survive the impact of the external dynamics and be able to recover from any initial shocks.

Adaptability differs from the agility in that it deals with more long-term and fundamental changes in the overall external environment, which is often irreversible. Adaptability calls for organization and its supply chain to embark on major strategic changes in technology, market positioning, radical skill upgrading and competence shift. It helps the supply chain to survive the long waves of external dynamics.

Alignment is a supply chain capability that coordinates and balances the interests of all members. It addresses the supply chain’s internal dynamics and ensures the supply chain to remains a stable and cohesive whole. It also means to align all the complementary resources and optimize the operational effectiveness and relationship to deliver a competitive advantage.